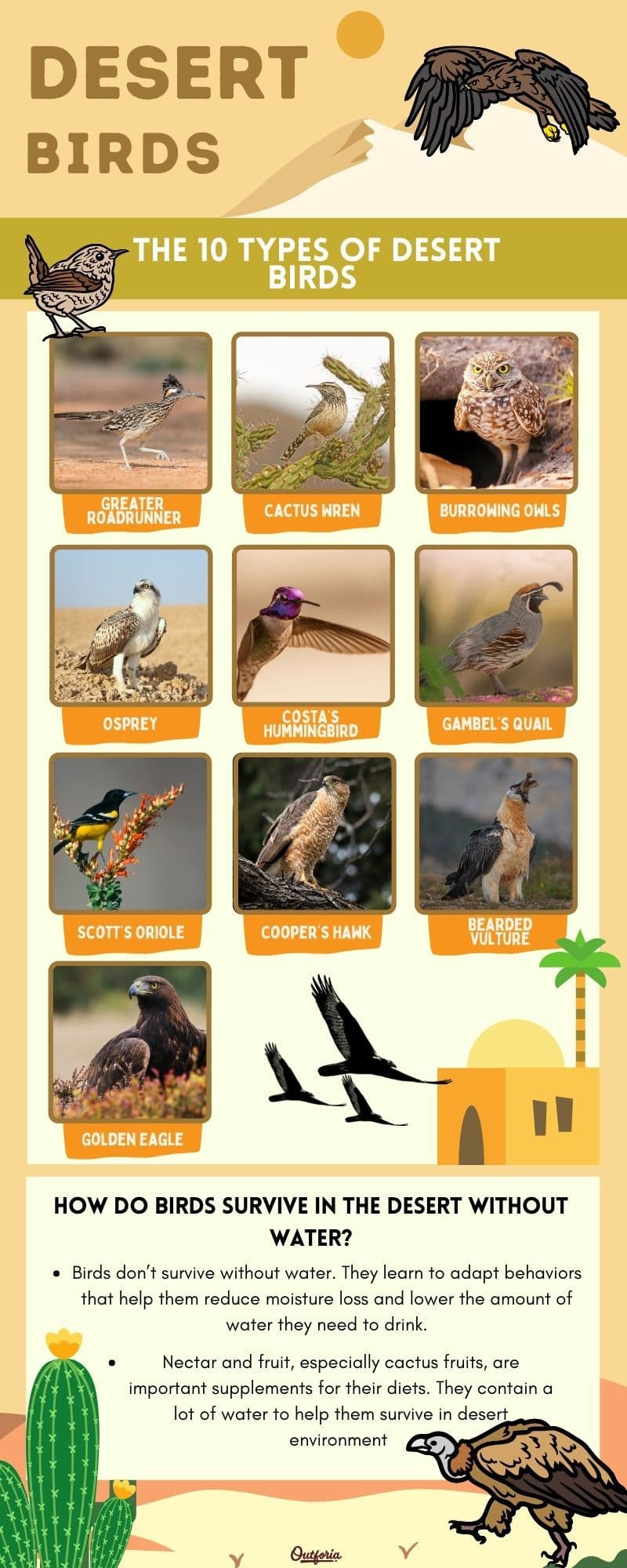

Deserts are some of the harshest environments on the planet. To the untrained eye, they can seem like vast landscapes that are devoid of life. Many kinds of animals thrive in desert environments, including some very special birds.

We’ll describe some interesting species of birds you can find in deserts around the world and then explain some unique behaviors that allow them to survive in such arid climates.

SHARE THIS IMAGE ON YOUR SITE

<a href="https://outforia.com/desert-birds/"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/desert-birds-inforgraphic.jpg"></a><br>desert birds <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>10 Birds You Can Find In The Desert

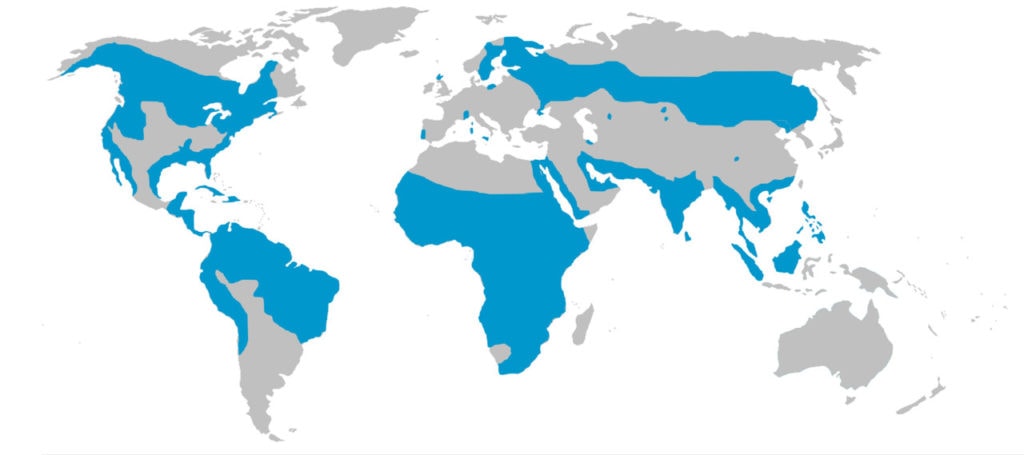

Birds can be found in nearly every terrestrial environment on Earth. Many of the birds in the below list are found in the deserts and scrublands of the western United States, however, you’ll find some bird species in every desert in the world.

1. Greater Roadrunner

Most people don’t know that the Roadrunner from Looney Tunes cartoons is based on a real species of bird! While not quite as fast as their cartoon character named after them, they’re incredibly fast and fascinating birds.

Roadrunners have a distinctive shape that helps you identify them. They tend to have very long legs, elongated bodies, very long tails, and long necks. Their bill has a downward curve and they also have a crest of feathers atop their head like a mohawk. Most will have brown or tan plumage with black streaks, a black head crest, and blue skin behind the eyes.

Pio2009 / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikimedia commons

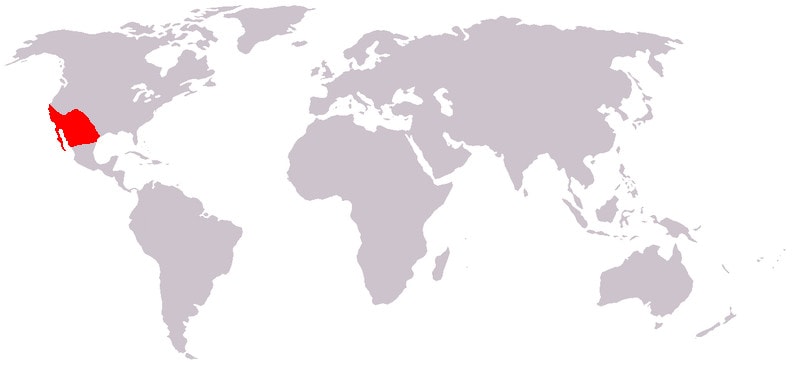

Greater roadrunners can be found throughout the southwestern United States from sea level to elevations of 10,000 feet (3,000 meters). Most of the time, they prefer the scrubby environments of grasslands, canyons, and areas dominated by mesquite.

Roadrunners feed on other animals including insects, small mammals, different frogs, reptiles, and other birds. They’re not picky eaters, taking pretty much anything they can catch. Their diet adapts to eating more seeds, fruit, and plants to make up for limited prey opportunities in the winter.

Some fascinating roadrunner behavior includes repeatedly pecking rattlesnakes to kill them or slamming reptiles and mice into rocks to make them easier to swallow. They don’t fly very well and instead race across well-worn paths very quickly, scanning their territory and driving off intruders.

Greater roadrunners mate for life and “renew their vows” each spring through elaborate courtship rituals. Once or twice per year, the female lays a clutch of 2-6 eggs in nests off the ground and next to one of their paths. The species is considered to be stable globally, but regional populations may be in decline.

2. Cactus Wren

Cactus wrens are the largest wrens in the United States. They have rounded, chunky bodies, thick bills, a long tail, and rounded wings. Most cactus wrens have a speckled plumage of white and brown, with white marks above their eyes that look like eyebrows.

The natural range of cactus wrens includes the Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mojave Deserts, as well as the scrub and thorn scrub areas of California and Mexico. Their most populated areas overlap with the densest areas of cacti and scrub such as saguaros, prickly pears, yucca, mesquite, willows, and shrubs.

Imagesincommons / CC0 / Wikimedia commons

Insects make up the bulk of a cactus wren’s diet, including spiders, beetles, grasshoppers, and butterflies. They also eat many cactus fruits, which is where they get the majority of their water.

Cactus wrens are easy to find since they constantly announce their presence from atop cacti or hop around in the open. Though fairly small, if a wren discovers a predator near their nest, they will mob and rush it to attempt to drive it away. Snakes, domestic cats, hawks, roadrunners will all prey on the wrens and their eggs.

Adults pair up for breeding but may decide not to breed in times of extreme drought. One to three times per year, females lay a clutch of two to seven eggs. Cactus wren populations have declined for the past sixty years, mostly due to urban and agricultural expansion.

3. Burrowing Owls

Burrowing owls are cute, tiny little owls that make their homes in holes in the ground. They have long legs, lack typical owl ear tufts, and bright yellow eyes. Adult’s plumage is typically brown with mottled, sandy-colored spots, with a white underbelly and throat.

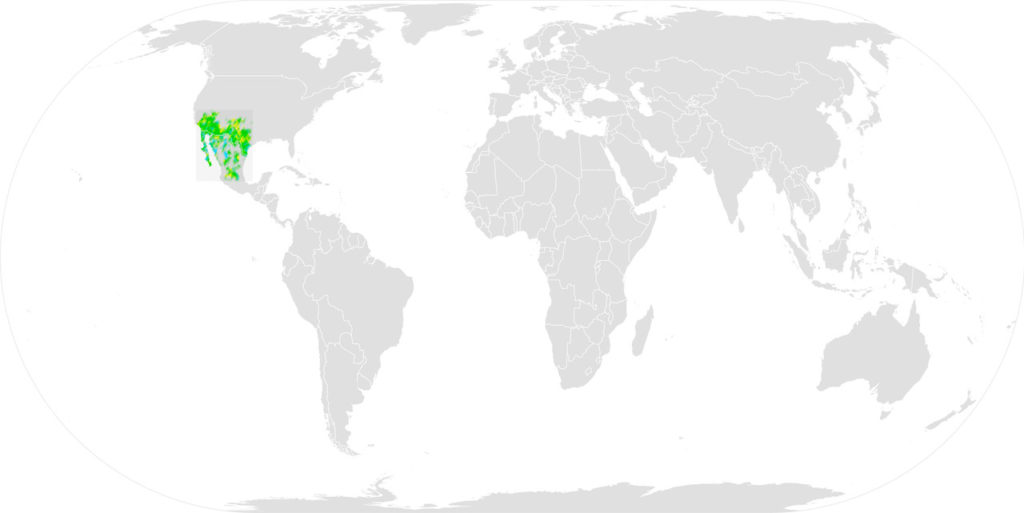

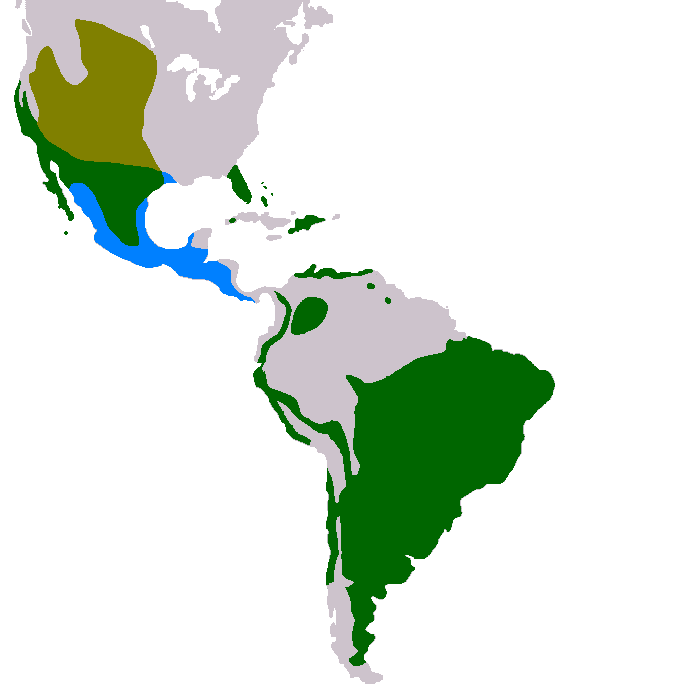

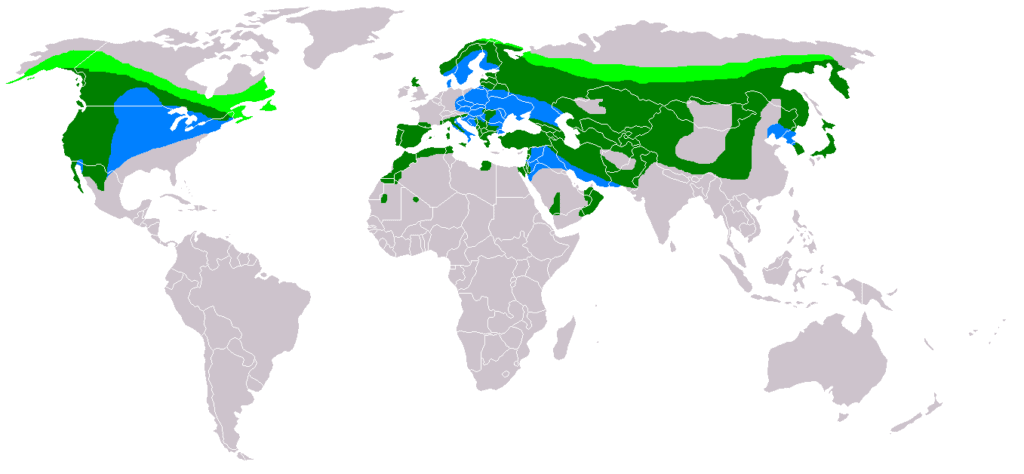

These owl species tend to live in the open areas of sloping grasslands, deserts, and steppes. They can also adapt quickly to an urban environment and make their homes on golf courses, around airports, and in drainage areas. Their natural range extends across the southwestern United States, Mexico, and the western side of South America.

Yellow: summer breeding range

Green: resident breeding range

Blue: winter non-breeding range

Minzinho (talk) / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikimedia commons

The bulk of a burrowing owl’s diet is vertebrates, including small mammals, lizards, and small birds. They also eat a wide variety of insects such as grasshoppers, crickets, and moths.

Burrowing owls sleep a lot, inside their burrows, in depressions in the ground, or on mounds of dirt. When disturbed, they bob up and down like confused kids. While they can fly, they tend to stay close to the ground, gliding or hovering as they scan for prey.

Most of the burrows they live in are dug by other animals such as badgers, shrews, or prairie dogs. Females lay between two and twelve eggs per clutch, with hatchlings being cared for by both parents until they can hunt for themselves.

4. Ospreys

Ospreys are large, migratory birds that are unique among raptors for their ability to dive underwater. They tend to breed in northern regions within Canada, migrating through the deserts of the southwestern United States on their way to winter homes close to the equator.

Zoologist / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikimedia commons

An osprey is a distinctively shaped hawk, having a slender body, long legs, and narrow wings. Their wings have a kink in them in flight, making them look like a flying letter “M.” Their backs are brown and their undersides are white, with a brown streak through their eyes and a white head.

Ospreys feed almost exclusively on fish. They snatch fish from the surface or dive underwater to grab them in both salt and freshwater. They’re also known to eat snakes, small mammals, and salamanders.

Since ospreys require a water source to find food, you’ll find them mostly around desert lakes, oases, or rivers. Most of their lives are spent alone, however they engage in spectacular breeding rituals where they tangle talons and dive through the sky.

Pesticides are one of the largest threats to ospreys. Like pelicans, they were hit hard by DDT runoff from farms entering water sources and the fish swimming in them. When they eat the fish, they also begin to intake the pesticide. Today, they aren’t a species of concern, mostly thanks to banning specific pesticides.

5. Costa’s Hummingbird

Costa’s hummingbirds are tiny hummingbirds. Their compact nature means their tails barely reach their wings when they’re folded up. Males have a deep purple crown, green vest, and green back. Females are mostly green with white eyebrows and a white belly.

The natural range for these hummingbirds includes southern California, the Baja region of Mexico, and parts of Nevada and New Mexico. They most frequently occur around dense regions of sage scrub and flowering cacti.

The bulk of a Costa hummingbird’s diet is nectar from sage, chuparosa, and ocotillo. They will also eat small amounts of tiny insects to help supplement their nectar-based diet.

Because of a vast decline in population, these hummingbirds are a species of concern according to the Partners in Flight, but they are not on any watchlists.

6. Gambel’s Quail

Gambel’s Quail are ground foragers found year-round throughout the Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan deserts. They have a distinct color pattern of gray, chestnut, and cream. Males have a large crest, chestnut sides, and a whitish belly. Females are grayer and have a muted color palette.

These quail walk across the ground in groups of twelve or more, scratching for food under shrubs and cacti. The bulk of their diet is made of seeds from grasses, shrubs, trees, and cacti. When startled, the group will suddenly burst into flight and scatter.

Most quail nests will be built in areas hidden by vegetation, such as inside thickets or under dense shrubbery. Females lay one or two clutches of two to fifteen eggs each year. Babies are immediately able to leave the nest and follow their parents in search of food.

Gambel’s quail are not considered an at-risk species, however, judging their population stability is difficult. Quail are notoriously a boom or bust species on a yearly basis, with weather patterns affecting their breeding schedule.

While they are a popular species to hunt, strict bag limits were found to have little impact on population health. Restricting grazing land seems to be a better management indicator for healthy quail populations.

7. Scott’s Oriole

Scott’s orioles are beautiful singers and stand out thanks to their bright plumage. Their natural range includes the southwestern United States and Mexico, but they are closely tied to dense areas of the yucca plants they depend on for shelter and food.

These songbirds have a long tail, a spike-shaped bill, and long wings for their body. Males have lemon-yellow bellies and black backs and heads. Their wings have white bars stretching across them as well. Females have a dull yellow belly, olive-colored backs, and fainter wing bars than males.

Scott’s orioles eat insects, fruit, and nectar. They chase insects across the ground, under every nook and cranny they can find, and through the air. Cactus fruits and flower nectar are also on the menu, with these birds even being attracted to hummingbird feeders.

Their behavior while hunting is very animated, with them hopping up and down and seeming to play up where they look. Sometimes these types of orioles will even suspend themselves upside down from a branch and swing themselves into position to check holes in trees.

The largest threats to Scott’s orioles include habitat degradation and destruction of breeding areas, however, they are not a species of concern.

8. Cooper’s Hawk

Cooper’s hawks are highly migratory birds, flying from summer breeding grounds along the Canadian border to southern regions of the United States and Mexico for winter. Identifying them can be tricky, as they closely resemble the smaller sharp-shinned Hawk.

They have a classic hawk shape, with rounded wings, a large head, and a very long tail. Adults have a steel-blue to gray back, white underside with reddish bars marking their bellies, and dark bands along the tail.

Birds make up most of a Cooper’s hawk’s diet, targeting medium-sized birds more often than small ones. They’ll also eat small mammals and sometimes even bats. In the desert, mammals make up a larger portion of their diet than in wooded forests.

Cooper’s hawks have stable populations and are not considered a species of concern. These hawk species aren’t the most populous bird of the desert, but they make their way through the southwestern United States on a yearly basis, terrorizing grouse, quail, and ground birds on their way to warmer regions.

9. Bearded Vulture

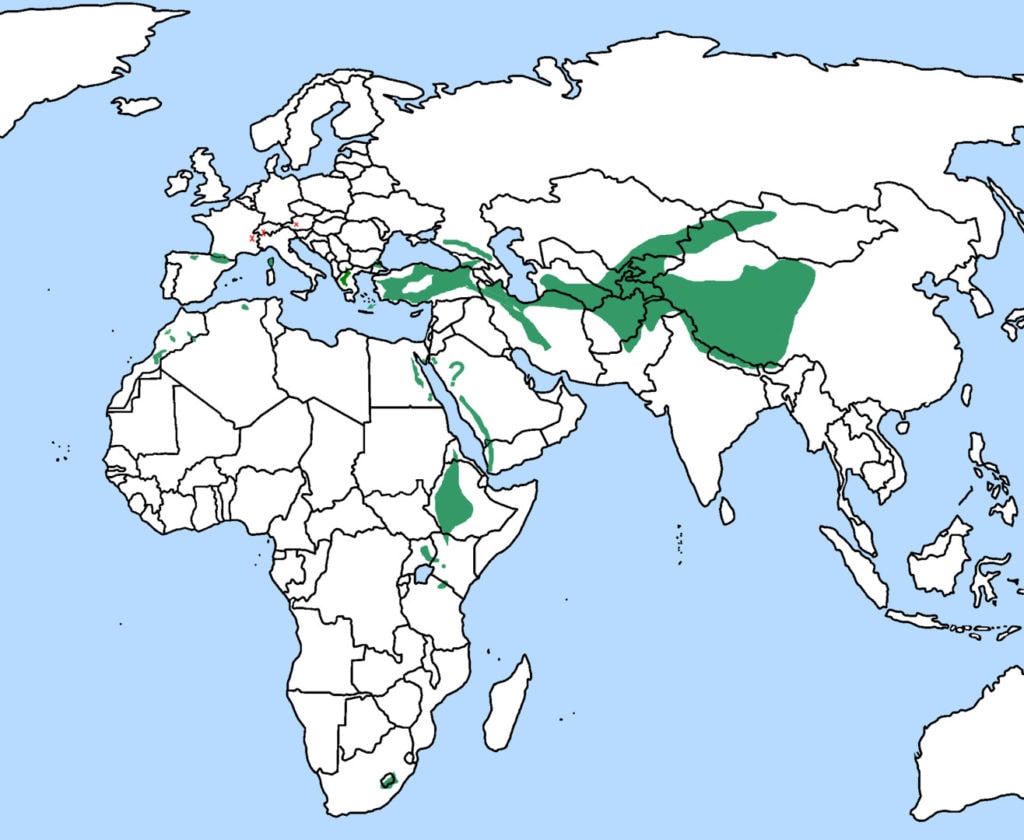

Found from Africa to the Gobi Desert of Mongolia and the Himalayan Mountains to Europe, the bearded vulture is a threatened species that prefers to soar along ridgelines and mountains. They have albatross-style wings and a diamond-shaped tail. They are mostly slate gray with a rust-orange belly and dark underwings.

Up to ninety percent of a bearded vulture’s diet consists of bone and bone marrow. For the most part, they love above 3,000 feet in elevation, soaring high above the ground and scanning for carcasses to feed on.

No machine-readable author provided. Scops~commonswiki assumed (based on copyright claims). – No machine-readable source provided. Own work assumed (based on copyright claims)./ CC BY-SA 3.0/ Wikimedia commons

Even from far away, bearded vultures can be easy to spot. Their wingspan can be as much as 9.3 feet (2.8 meters). One unique behavior they have learned is how to crack bones too large to swallow. They take large pieces high into the air and drop them, smashing them into easier-to-eat pieces.

While widespread, these birds are not migratory and will spend their entire lives in the range they were born in. Human development is the main reason why they are a threatened species, however, they naturally occur in a low density in all of their natural ranges.

10. Golden Eagle

Golden eagle populations break down into moth migratory and year-round groups. They’re huge, fast, and nimble eagles that have been known to defend their nests from animals as large as bears.

As one of the largest birds in North America, it comes as no surprise that golden eagles have a huge wingspan of up to 72.8-86.6 in (185-220 cm). They’re mostly dark brown in color with a golden sheen on the back of the neck and head.

Small to medium-sized mammals make up the majority of golden eagle’s diets. They’ve been known to take down domestic livestock, deer, and large birds, and will feed on fish. Sometimes, they will follow crows and feed on carrion.

Even seals, coyotes, bighorn sheep, badgers, and bobcats have been observed to be killed by golden eagles. They’ve got a true attitude when it comes to defending their nests and young, mobbing and fighting against large predator species whenever necessary.

The Engineer – / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikimedia commons

Year-round populations can be found across the western United States, however, breeding areas for golden eagles extend as far north as Alaska and the birds will migrate into the northwestern regions of North America as well.

Golden eagles are not considered a species of concern, with stable population numbers. They still deal with threats such as eating poisoned prey animals set out for coyote control, hunting, and collisions with human structures. It’s estimated that up to 70% of golden eagle deaths are due to human action, whether directly or indirectly.

You may also like: Check Out These 25+ Amazing Types of Falcons and Where You Can Spot Them: Complete with Images, Facts, and More!

How Do Birds Survive In The Desert Without Water?

Quite frankly, birds don’t survive without water. In desert environments, birds have adapted to learn behaviors that help them reduce moisture loss and lower the amount of water they need to drink.

Most birds will tuck themselves into shaded areas in the hottest parts of the day. This helps lower their body temperature so they don’t pant as much. Panting causes them to lose water, so limiting that action keeps them hydrated.

Desert birds also typically have extremely efficient kidneys. They excrete almost no liquid and use the water inside even the driest of foods to aid digestion. Some birds may never physically drink water throughout their lives.

Nectar and fruit, especially cactus fruits, are important supplements for many desert birds’ diets. They contain a lot of water, giving birds the moisture they need to survive in areas without consistent water sources.

Temporary water sources such as puddles after a rare rain shower give birds a break from their strategic water shortages. Many birds simply live near sources of water such as oases, rivers, or lakes in the desert.

Birds have the advantage of flight, allowing them to scan vast regions for water sources and then fly directly to them instead of navigating tough topography. Quite simply, birds can’t survive without water, but they’ve adapted to be able to find it or get enough water through food sources to survive.

You may also like: Learn More About the Top 15 Long-Necked Birds You Can’t Miss: Complete with Images, Facts, and More!

Bird Migration Explained

How Do Birds Navigate?

Birds migrate the same paths year after year and rarely seem to get lost. How they navigate isn’t fully understood, however, they use multiple different senses to figure out where to go.

The sun, moon, and stars are all possible sources of information for birds to navigate. It’s also known that they can sense the earth’s magnetic field and can remember landmarks that help them know they’re on the right course.

In most cases, birds don’t fly straight to their final destination for long distances, they instead stop at “rest areas” along the way where they can eat and rest their wings. These shorter flights between spots make each flight easier to navigate.

How Far Do They Travel?

Bird migration can be categorized into four types based on distance:

- Permanent Residents

- Short-distance Migrants

- Medium-distance Migrants

- Long-distance Migrants

Permanent residents do not migrate. They’re able to find food, nesting sites, and resources year-round where they are located.

Short-distance migrants make small movements in search of food. These can be as small as a few miles or up and down in elevation on a mountain range.

Medium-range migrants cover distances up to a few hundred miles.

Long-distance migrants go the furthest. They typically move as far as from Canada and the United States to South or Central America. These migration paths can be as long as 16,000 miles (25750 kilometers).

What Causes Birds to Migrate?

Bird migration is tied to resources, mostly including food or nesting sites.

Many birds that migrate north do so to take advantage of booming insect populations during the spring. As the weather gets colder, food sources drop off so those same birds migrate back into southern regions where food is more plentiful.

Ambient temperature can affect not only breeding but also the bird’s eggs and their chances of successfully reproducing. Many birds will move to areas with more consistent food sources to ensure their chicks have the chance to grow.

The trigger for migration is still being researched today. A combination of factors likely tells birds that it’s time to go, including the length of daylight hours, temperature shifts, change in the food supply, or genetic memory.