The term “pine” tends to be used interchangeably with words like “evergreen” and “conifer.” However, a pine tree is technically only a species of conifer within the Pinus genus. There are about 120 species of pines scattered throughout the world.

If you are trying to identify a pine tree or learn about the species found across the globe, you are in luck. We have compiled a list of many of the pines, their families, and how they are identified. From America to China, pine trees are everywhere.

Parts of Pine Trees

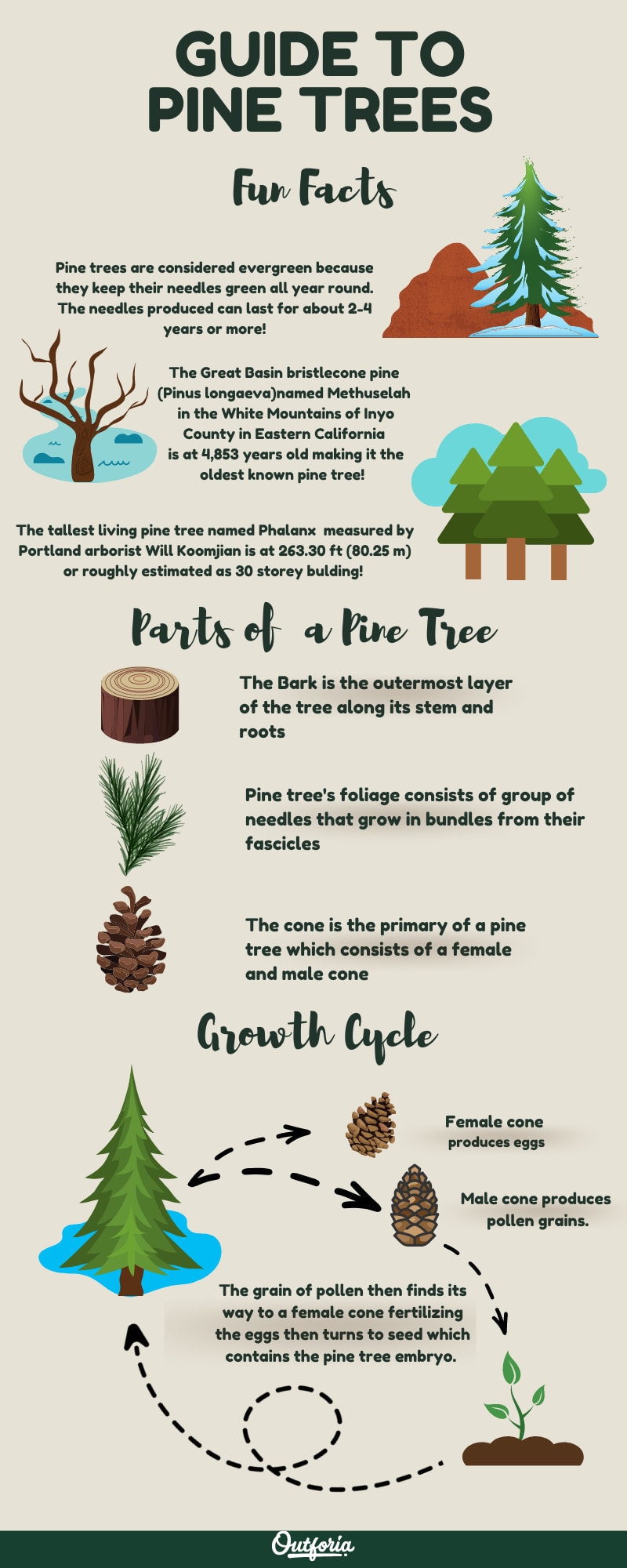

Pine trees have a similar growing style to any other conifer. They have three main exterior parts, including their bark, foliage, and cones.

These three facets also include the primary ways you can identify trees apart. Sometimes the differences between them are small, and you have to have a keen eye. Other times, you will be able to tell the difference in an instant just by looking at the type of bark.

1. Pine Tree Bark

The bark of any tree is its outermost layer along its stem and mature roots. The bark is made up of layers of the vascular cambium and protects the more vulnerable interior of the tree. Many trees have two primary layers, the inner and the outer bark layers.

Pine bark has also been studied as an herbal extract. It contains certain kinds of flavonoids that can work as an antioxidant. Not all pine bark is as nutritious as this, but most pine bark extracts have been promoted to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.

2. Foliage

Pine trees have a unique leaf structure. They each have four types of leaf, depending on the stage of the tree and leaf. These leaves include the cotyledons, juveniles, scales, and the actual needles.

Cotyledons (Seed Leaves)

The cotyledons are seedlings that grow in a whorl. There can be anywhere from four to 24 of them in a whorl. These only occur when the pine tree has first grown above ground from the seed.

Juvenile Leaves

The juvenile leaves then emerge from the seedling as it becomes a young plant. These look similar to the cotyledons but will ultimately be more substantial. They range in length from 0.8 to 2.4 inches (2 to 6 cm). They will often be green or blue-green arranged in a spiral around the shoot.

Scale Leaves

Scale leaves arrange themselves in a spiral around the juvenile leaves. These function and look similar to bud scales.

Needles

The needles are the adult leaves of a pine tree. They grow in bundles from their fascicles. Their bundles can be from one to seven per fascicle. These leaves are evergreen and persistent. They can last anywhere from 1.5 years to 40, species-dependent. Here’s a fun fact, pine needle is one of the edible plants that you can forage while hiking on the Appalachian Trail.

3. Pine Tree Cones

The final primary part of a pine tree is the cone. Pines typically grow both the male and female cones on the same tree. The pine cones protect the seeds inside. Although some of them grow open, others will only open under specific circumstances.

You may also like: Are Pine Cones Edible? Pine Trees As Nature’s Larder

The Growth Patterns and Lifespan of Pine Trees

The growth patterns and lifespan of pine trees vary from species to species. It has quite a bit to do with their range. For example, many subalpine species live for 30 years in their native climate. However, in optimum growing conditions, they can live up to 80 years.

On average, most pine tree species will grow somewhere between one to two feet each year. However, many trees grow slower than this, and there is a number that grows faster, including the Eastern White Pine.

Pines are known for their long life spans. Most pine species are pretty long-lived. They can live for anywhere from 100 years to 1,000 years.

The longest living species of pine is the Great Basin Bristlecone Pine (Pinus longaeva). There is one tree in particular that has been dubbed among the world’s oldest living things. Scientists estimate this tree has been around for about 4,800 years.

You may also like: Exploring The 20 Weirdest And Most Amazing Types Of Pine Cones

Pine Trees FAQ

How do pine trees spread their seeds?

The exact method depends on the species. Often, the seeds have wings. That way, when the cone opens, the wind will take them out of the cone and disperse them. Certain species rely on animals to spread their seed. One example of this is the Pinyon Jay with the Colorado Pinyon.

Is pine sap useful?

Pine tree sap is very useful for the tree. When inside the tree, it helps to transport nutrients throughout the tree. Humans use pine sap to make products like candles, glue, and turpentine. It is highly flammable, which makes it useful while camping for starting fires.

Is pine wood a suitable building material?

Pinewood makes an excellent building material. It is useful for building anything from furniture to houses. Although it is softwood, it is durable and shock-resistant. That helps it to compete well against hardwood like oak.

How do wildfires affect pine trees?

In environments where fires are naturally more common, certain pine species have developed resistance. Their bark can put up with fire much better, making them susceptible only to the hottest, longest fires. Some pine species can only spread through the use of fire. The cone is sealed shut with a strong resin that will only be melted in a hot fire. The seeds are resistant to fire and spread in the wind.

How do invasive insects like Pine Bark Beetle devastate pine forests?

Pine Bark beetle attacks certain species of pine. They can effectively decimate entire forests that have species like lodgepole pine, limber pines, and whitebark pines. They create holes in the bark called “pitch tubes.” They eventually end up destroying the vascular system of the tree, and it dies.

You may also like: Different Types of Mountains Across the World: How They’re Formed, Images, and More!

Classification of the Types of Pine Trees

Share this image to your site

<a href="https://outforia.com/types-of-pine-trees"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/types-of-pine-trees-1-410x1024.jpg"></a><br> Types of Pine Trees Infographic by <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>Pine trees have a relatively simple classification system compared to other trees, insects, or animals. All pine trees fall under the Pinus genus, the family Pinaceae, the Order Pinales, and the class Pinopsida.

Within the genus, there are two subgenera; the subgenera Pinus and Strobus. Each of these two has two sections that further delineate the various tree species. From there, the section gets broken into two or three subsections where the individual species are placed.

There is a group of pine trees called Incertae sedis. The Latin translates to “of uncertain placement.” Depending on the concerned plant or animal, the problem might be because of the plant’s broader relationships or unknown relationships to closely related taxa.

In the case of pine trees, the four unclassified species aren’t in a subgenus because they have been extinct for many years. There has been fossil evidence of their existence, but not enough to clarify their relationship to modern species.

Now that you have a clear layout for the types of pine trees classified let’s jump into their characteristics. First, we will work our way through each subgenus, giving examples of species in the various sections and subsections.

You may also like: 21 Different Plant Species Around the Globe From Prehistoric Times to Modern Times: Complete with Description, Images, and More!

The Types of Pine Trees

1.0 Subgenus Pinus: Hard and Yellow Pines

The Pinus subgenus primarily includes the hard and yellow pines. Most of these pines will have one to five needles per fascicle. A fascicle is the portion of the needles that connect the needs to the branch. It is often shaped like a cup.

There are other identifiers that scientists use to classify species under this subgenus. However, they often need to be seen with a microscope, such as the number of fibrovascular bundles per needle.

Another way for non-scientists to identify these kinds of pines is via their cones. The cone scales tend to be thicker and more rigid than in the other subgenus. These cones often open soon after they mature.

The Pinus subgenus is divided into two sections, including Pinus and Trifoliae.

1.1 Section Pinus

The Pinus section has either two or three needles in each fascicle. All the species in this section have cones with thick scales.

All these open at maturity, except for Pinus pinea. Most of these species are native to Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean, except for Pinus resinosa and Pinus tropicalis, covered in more detail below.

1.1.1 Subsection Pinus

These pines are related because of their geographical proximity to each other except for the two identified above. Our list of species below doesn’t include all the species in this subsection. Instead, it focuses on the most influential or well-known species. There are about 19 species total in the subsection, and we cover the top six.

1.1.1.1 Korean Red Pine (P. densiflora)

The Korean Red Pine also has the name Japanese Red Pine since its range includes both countries. The pine also grows within northeastern China and the very southeast of Russia. In these areas, the tree has become quite famous for timber production and as an ornamental species. That is why there have been several cultivars created for better ornamental growth.

In the winter, this pine becomes yellowish. It has needles that range from 3.1 to 4.7 inches (8 to 12 cm). Naturally, the tree grows to 65 to 114 feet (20 to 35 m). As many pines do, it prefers to receive full sun on a site with slightly acidic, well-draining soil. However, there are enough of them that these pines are classed as “Least Concern” in terms of environmental threats by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN)

1.1.1.2 Mountain Pine (P. mugo)

The Mountain Pine has many common names. These include bog pine, mugo pine, dwarf mountain pine, creeping pine, and scrub mountain pine. It naturally grows in high-altitude habitats throughout Central and Southeast Europe. Because of its elevation preference, ornamental varieties have been grown in the Rocky Mountains in North America.

The Mugo Pine has dark green needles that grow in pairs. The needles are 1.2 to 2.8 inches (3 to 7 cm) long. It has multiple subspecies. Since this pine is happy to grow in poor soils, it can become invasive when introduced to fragile habitats. Because of this, the tree is of Least Concern.

1.1.1.3 Tropical Pine (P. tropicalis)

There is less known about the Tropical Pine, likely because of its smaller range. Did you know that Cuba has pine forests? The Cuban pine forests are tropical coniferous forests with specific species that appreciate the humid, hot climate.

The Tropical Pine populates these forested areas. It is not currently found outside of the western islands in which it is endemic. That is likely why it has received the classification of a Vulnerable species.

1.1.1.4 Red Pine (P. resinosa)

The Red Pine, also known as the Norway Pine, is one of the few trees native to North America in this section. It grows from Newfoundland, Canada, into Manitoba and south into Pennsylvania. It is even the state tree of Minnesota.

You might note that this endemic range doesn’t include Norway. The theory is that Norwegian immigrants called the American Red Pine the ‘Norway Pine’ because of its visual similarity to their Scots Pine. It is a vivacious tree in the Least Concern category.

1.1.1.5 Scots Pine (P. sylvestris)

The Scots Pine is one of the most recognizable species in this section. Its other names include the European Red Pine, the Scotch Pine, and the Baltic Pine. The tree is more obvious to identify because of its shorter, blue-green needles coupled with orange-red bark.

This pine is endemic to Eurasia but has been shipped abroad and now grows in many areas of the world with a similar climate. The tree prefers poorer, sandy, or rocky soils. In fertile areas, it gets out-competed by broad-leaved trees or spruce.

1.1.1.6 Huangshan Pine (P. hwangshanensis)

The Huangshan Pine comes from the mysterious mountains of Eastern China. It gets its name from the Huangshan Mountains in the Anhui province, but its range extends further than this. Because of its dense growth and broad range, it is in the Least Concern category.

The Huangshan Pine grows to between 49 to 82 feet (15 to 25 m). It has a broad, flat crown made up of long branches that grow horizontally. The bark is unique because of its grey, plated look, almost like armor.

1.1.2 Subsection Pinaster

The following subsection under the Pinus subgenera is the Pinaster subsection. These species are endemic to the Mediterranean except for Pinus roxburghii. That pine comes from the Himalayas and has a unique cone that lacks spines on the scales. Otherwise, the trees below grow in a standard fashion for this subsection.

1.1.2.1 Turkish Pine (P. brutia)

The Turkish Pine primarily grows in Turkey, as its name would suggest. However, its range also includes parts of Bulgaria, the East Aegean Islands, and part of the Middle East in Jordan and Cyprus. The tree prefers low altitudes between sea level and 2,000 feet (600 meters).

This pine is a medium-sized tree growing between 20 to 35 meters (66 to 115 feet). It has a unique orange-red bark that is deeply fissured towards the base of the trunk and flaky toward the crown. Its broad range provides its Least Concern status.

1.1.2.2 Stone Pine (P. pinea)

The Stone Pine has a unique growth habit. Because of this, it also goes by common names such as the Umbrella and Parasol Pine. It is endemic to the Mediterranean, South Europe, the Middle East and has naturalized in North Africa and South Africa. It was introduced to North Africa more than a millennia ago, making it barely indistinguishable from native species.

The Stone Pine has a fascinating history because of its edible pine nuts. It was cultivated throughout prehistoric times for these nuts. Although this isn’t as common now, horticulturalists still cultivate them as ornamental trees. Therefore, they have a Least Concern status.

1.1.2.3 Canary Island Pine (P. canariensis)

The Canary Island Pine is endemic to the outer Canary Islands. It is a subtropical pine that doesn’t tolerate low temperatures. However, because of its mist-capturing foliage, this pine is extremely drought-tolerant in warm conditions. Although its range isn’t expansive, it grows densely throughout its growing zone and has received Least Concern status.

1.1.2.4 Maritime Pine (P. pinaster)

The Maritime, or Cluster Pine, is a tree that grows quickly and with hardwood. It has small seeds that have wings to take them far away from the mother tree.

Although it is endemic to the Mediterranean, it has been an invasive plant in Europe and particularly South Africa for 150 years. It was supposed to be only commercially planted as a timber resource. However, it tends to invade large areas quickly and outcompete natural vegetation.

1.1.2.5 Bosnian Pine (P. heldreichii)

The Bosnian Pine is native to the mountainous regions of the Balkans and southern Italy. The tree grows up to 82 to 115 feet (25 to 35 m) tall with a trunk diameter between around 6 feet (2 meters) when mature.

This pine is another in the hard pine group. The cones help to identify it since they have thin scales with a fragile build. The cones are a dark purple before they mature, only turning brown when ripe. Their seeds are long with wings. The trees have a Least Concern status.

1.1.2.6 Aleppo Pine (P. halepensis)

The Aleppo Pine also goes by the Jerusalem Pine. The tree is highly drought-resistant, making it a valuable tree in landscapes with hot climates. It is native to the Mediterranean but has been imported to grow in similar climates, such as California. However, it can be invasive, particularly in areas burned by fire.

This tree has an open crown with two or three needles per fascicle. The needles are light, yellow-green. Because of its vigorous growing habitat, it has a Least Concern status.

1.2 Section Trifoliae

This section is more commonly called the American Hard Pines. Its Latin name translates to “three-leaved.” However, that can be misleading since the species can have two to five needles per fascicle. This section includes all but two species of American hard pines.

1.2.1 Subsection Australes

This species in this subsection is native to North and Central America. Some of them also grow on certain Caribbean islands. There are some species whose presence in this subsection is debatable. Sometimes, they are put in the Attenuatae subsection. These include P. attenuata, P. radiata, and P. muricata.

1.2.1.1 Caribbean Pine (P. caribaea)

The Caribbean Pine is native to the West Indies and Central America. It prefers tropical and subtropical coniferous forests. Since 2013, there have been three accepted varieties of this pine, all receiving the Least Concern status.

The ecology of this tree is quite interesting. It is a species whose distribution heavily depends on periodic wildfires. It regenerates quickly after a fire since adults are resistant to fire. It replaces broadleaf trees until they get outcompeted by the same trees later in life.

1.2.1.2 Gregg’s Pine (P. greggii)

Gregg’s Pine is native to only two regions in eastern Mexico. Because of its sensitivity and a small range, it has received a Near Threatened status. It is a more fragile-looking tree since it has slender branches and soft clusters of needles. The branches and the upper trunk are often relatively smooth. Only old trees have rough bark at the trunk’s base.

1.2.1.3 Lawson’s Pine (P. lawsonii)

Lawson’s pine has medium-length thin needles. Its range only includes some of Mexico, but it grows well enough to have a Least Concern status.

1.2.1.4 Bishop Pine (P. muricata)

Bishop Pine has a very restricted range. It only grows in parts of California near the coast, on the Channel Islands, and in a few locations within Baja California, Mexico. Due to its decreased distribution, it has a Vulnerable classification. The common name for this pine comes from its first identification near the Mission of San Luis Obispo.

1.2.1.5 Longleaf Pine (P. palustris)

The Longleaf pine is a species native to the Southeastern US. These trees grow between 98 to 115 feet (30 to 35 meters), although they reportedly grew up to 154 feet (47 m) before extensive logging changed their growth habit.

This tree has become a cultural symbol for its native area. It is also the official state tree of Alabama. Unfortunately, due to its growth, timber trade, and pollination requirements, the longleaf pine has become an Endangered species.

1.2.1.6 Pitch Pine (P. rigida)

The Pitch Pine grows across Eastern North America. These pines prefer to grow in areas where other species wouldn’t be able to grow. That includes soils low in nutrients that are sandy or acidic. The tree is also capable of naturally hybridizing with other species and has thus created its subspecies. Because of these characteristics, the tree has the Least Concern status.

1.2.2 Subsection Contortae

The following subsection is the second of the three subsections in the Trifoliaea section. It only includes four species, so we have covered them all. The species are native to both North America and Mexico.

1.2.2.1 Jack Pine (P. banksiana)

The Jack Pine is native to eastern North America. It also has the common names, Grey Pine and Scrub Pine. At the western edge of its range, it hybridizes with the Lodgepole Pine. These trees range from 30 to 72 feet (9 to 22 m).

In poor growing conditions, some jack pines will mature at shrub size. Regardless of growing conditions, they often don’t grow perfectly straight, giving them an irregular shape that resembles the Pitch Pine. They reseed burnt ground quickly, resulting in the Least Concern status.

1.2.2.2 Sand Pine (P. clausa)

The Sand Pine’s other common names include the Florida Spruce Pine, Alabama Pine, and Scrub Pine. It is endemic to the Southeastern US. These trees almost exclusively grow in infertile, excessively drained, sandy soils. That is because they cannot outcompete other species in better soil types. As a result, it is one of the few canopy trees in Florida’s scrub ecosystem.

1.2.2.3 Lodgepole Pine (P. contorta)

The Lodgepole Pine has an expansive range compared to the other members of this subsection. The other common names include the Shore Pine, Twisted Pine, and Contorta Pine. It prefers to grow close to the ocean in dry montane forests or subalpine zones. They avoid lowland rain forests common to the Northwest. Because of its more extensive range, it has received a Least Concern status.

1.2.2.4 Virginia Pine (P. virginiana)

The last of the four species in this subsection includes Virginia or Jersey Pine. It prefers the poor soil types in Long Island and the Appalachian Mountains. The tree typically grows between 18 to 59 feet (9 to 18 m) tall, although it grows taller if allowed to populate in optimum conditions.

1.2.3 Subsection Ponderosae

The next subsection is the last one in this section and the final section of the Pinus subgenus. It contains quite a few trees those in the United States will be familiar with, such as the Ponderosa Pine. Most of these species are native to Central America and the western US, and Canada.

1.2.3.1 Arizona Pine (P. arizonica)

The Arizona Pine is a medium-sized pine that can grow between 80 to 115 feet (25 to 35 m) tall. The needles grow in bundles of three, four, or five. The variation in the needle grouping is thought to be because it is a variant of the Ponderosa Pine. It has established itself as a distinct species, recognized by most authorities since 1997. It has a status of Least Concern.

1.2.3.2 Cooper’s Pine (P. cooperi)

Cooper’s Pine is native to specific areas in Central Mexico. It is a medium-sized pine with a standard, conical growth structure.

1.2.3.3 Ponderosa Pine (P. ponderosa)

The Ponderosa Pine uses quite a few names, including Bull Pine, Blackjack Pine, Filipinus Pine, and Western Yellow-Pine. The most characteristic trait of the Ponderosa Pine is its very long needles and its unusually tall height. Since it is the most widely distributed pine within North America, it has a Least Concern status.

The Ponderosa Pine has needles ranging between 3.6 to 8.1 inches (9.2 to 20.5 cm) in length, depending on the subspecies you have. There are four primary subspecies of Ponderosa with distinct ranges in North America.

1.2.3.4 Gray Pine (P. sabiniana)

The Grey Pine also has the names Towani Pine, Foothill Pine, and the Digger Pine. However, that last name is discouraged since some find its history offensive. The tree is endemic to California.

This tree is the only food for the caterpillars of twirler or Gelechiid moths. The tree was also historically crucial since Native Americans relied on their sweet pine nuts and roots for sustenance.

1.2.3.5 Thinleaf Pine (P. maximinoi)

The Thinleaf Pine has a soft texture to it because of how thin and light the needles are. It is only found in El Salvador, Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala. The bark of the tree is smooth until it ages quite a bit. It prefers to grow between elevations of 4,900 to 7,900 feet (1,500 to 2,400 m).

1.2.3.6 Jeffrey Pine (P. jeffreyi)

The jeffrey pine primarily grows in California, but you can also find it in parts of Oregon and Nevada. It gets its name from the botanist John Jeffrey, a Scottish plant-hunter. It is another large coniferous tree that can grow around 82 to 131 feet (25 to 40 m) tall. This tree is closely related to the Ponderosa Pine and quite similar to it in appearance.

2.0 Subgenus Strobus

The Strobus encompasses most of the white pines and the soft pines. Most of the species in this subgenus will have one to five needles in each fascicle. These pines include many species native to North America and range around much of the rest of the globe.

2.1 Section Quinquefoliae

2.1.1 Subsection Gerardianae

The Gerardianae subsection includes trees native to East Asia. The other relating factor between these three trees is that they have three to five needles per fascicle.

2.1.1.1 Lacebark Pine (P. bungeana)

The Lacebark or White-Barked Pine is a characteristic tree species of East Asia. It grows slowly and is quite frost-hardy, growing well in temperatures down to -14.8 degrees Fahrenheit (-26 degrees Celsius). The tree’s most defining feature is its white, lacy bark.

The white bark eventually sheds in round scales. The patches reveal pale yellow bark underneath, turning to deep red and purple when it hits the light. This pattern gives the bark its lacy appearance.

2.1.1.2 Chilgoza Pine (P. gerardiana)

The Chilgoza Pine is native to the northwestern Himalayas. It prefers to grow in elevations between 6000 and 11,000 feet (1,800 and 3,350 m). However, because of its elevated distribution, climate change is harming its growth. That has placed the species in the Near Threatened status. The bark of the tree is flaky, similar to the Lacebark Pine.

2.1.1.3 Qiaojia Pine (P. squamata)

The last species in this subsection is the Qiaojia Pine or Southern Lacebark Pine. It is one of the few pine trees on our list that is critically endangered. It only grows in Qiaojia County, located northeast of Yunnan, China, and above 7,200 feet (2,200 m) in elevation.

The pine was only discovered in 1991, and there is less known about it since none of the currently living trees are mature.

2.1.2 Subsection Krempfianae

This subsection only has one species in it, the Krempf’s Pine.

2.1.2.1 Krempf’s Pine (P. krempfii)

The Krempf’s Pine is a rare pine species, currently classed as a Vulnerable species. It is endemic to Vietnam, and even then, only the central highlands. The pine has flat needles, which is an entirely unknown characteristic in other pines and the reason it gets its own subsection.

2.1.3 Subsection Strobus

The following subsection is much bigger than the monotypic one before it. The Strobus subsection has pines with at least five needles on each fascicle. The needles in these species are pretty soft and flexible. The trees have ranges that span across the world.

2.1.3.1 Whitebark Pine (P. albicaulis)

The Whitebark Pine, also called the Pitch Pine, Creeping Pine, and Scrub Pine is an endangered species in Western North America. It is a subalpine species that doesn’t grow very tall, hence the ‘creeping’ moniker. These trees are often one of the species that mark the tree line along an alpine range.

2.1.3.2 Swiss Pine (P. cembra)

The Swiss Pine, Stone Pine, or Arolla Pine is a full-bodied pine species that grows in the Alps. It also makes its home in the Carpathian Mountains that span across central Europe. The tree grows along the alpine tree line in these areas, growing up to 115 feet (35 meters) tall even with the extreme climatic conditions.

2.1.3.3 Korean Pine (P. koraiensis)

The Korean Pine grows in Korea, China, Mongolia, and Japan. Another common name for it in English is the Chinese Pine Nut. This pine is in the white pine group. In its native habitat, it typically reaches about 100 feet tall (30 m).

It has a satisfying pyramidal shape that has gained its cultivation interest. In addition, the gray outer bark flakes off to reveal a beautiful reddish color, which helps identify it. It grows well in both native and cultivated conditions, so it is in the Least Concern category.

2.1.3.4 Sugar Pine (P. lambertiana)

The Sugar Pine is a gigantic species of pine tree. It also has some of the longest cones out of all the conifer species. The tree is native to the Pacific coast in North America. It grows as far north as Oregon and south as Baja California.

The Sugar Pine can grow between 130 to 195 feet (40 to 60 m) tall. The tallest specimen is in Yosemite National park and is 273 feet and 9 inches (83.45 meters) tall. Unfortunately, these trees do suffer from pine bark beetle attacks. Therefore most of the tallest and oldest specimens have recently died out. Even so, the tree is still classed as Least Concern.

2.1.3.5 Macedonian Pine (P. peuce)

The Macedonian Pine is a species native to the mountains in Macedonia, Albania, Bulgaria, and the bordering countries. It grows along the alpine tree line. The higher in elevation it grows, the more its height diminishes. The species subalpine range has been impacted by climate change, classifying it as a Near Threatened species.

2.1.3.6 Eastern White Pine (P. strobus)

The Eastern White Pine is a large Pine species native to most of eastern North America. The Native American tribe Haudenosaunee called this tree the “Tree of Peace.” The tree is steeped in legend, a grove of them said to be where the Peace-Giver created the Five Nations Confederacy between previously warring Native American tribes.

2.1.3.7 Blue Pine (P. wallichiana)

The Blue Pine is native to the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountains. It prefers to grow in a temperate climate. The tree also goes by the Bhutan Pine because of its dense presence in the mountainous country.

2.2 Section Parrya

The Parrya section includes pines with bundles of one to five needles per fascicle. They also have seeds with wings, although some have no wings at all. The trees in this section are primarily native to the southwestern portion of the United States and into Mexico.

2.2.1 Subsection Nelsonianae

This subsection is another with only one species of tree, the Nelson’s Pinyon.

2.2.1.1 Nelson’s Pinyon (P. nelsonii)

The Nelson’s Pinyon is an endangered species native to the mountains in northeastern Mexico. The tree has specific characteristics that separate it morphologically from any other species. It has been described as ‘exceptional’ by scientists doing DNA tests. The tree seeds are edible and very tasty, enjoyed by the people in their small range.

2.2.2 Subsection Balfourianae

The Balfourianae is the subsection of Bristlecone Pines, some of the longest living organisms in the world. They are native to the harsh climates found in the southwest United States.

2.2.2.1 Rocky Mountain Bristlecone Pine (P. aristata)

The Rocky Mountain Bristlecone Pine is a long-living species. It grows throughout the Rocky Mountains and into Mexico. It prefers to grow at high altitudes, between 7,000 to 13,000 feet (2,100 to 4,000 m). The tree frequently makes up the tree line in these areas since not many other plants want to grow in cold, dry subalpine conditions.

2.2.2.2 Foxtail Pine (P. balfouriana)

The Foxtail Pine has a unique growth pattern, with branches and needles that resemble foxtails. It prefers to grow in subalpine climates in California. The tree can grow to 30 up to 70 feet tall (10 to 20 meters). However, due to its climatic conditions, it tends towards the shorter end of the range.

2.2.2.3 Great Basin Bristlecone Pine (P. longaeva)

Great Basin Bristlecone Pine or Intermountain Bristlecone Pine includes specimens among the longest-living organisms in the world. They are endemic to the mountains of California, Utah, and Nevada. It has also become one of Nevada’s state trees.

The Bristlecone Pine is a medium-sized tree that typically grows between 16 and 49 feet (5 to 15 m) tall. They have bright orange bark that gets quite scaly at its base. The needles on this conifer have one of the most prolonged persistence of any plant. Some of them remain green for up to 45 years.

2.2.3 Subsection Cembroides

The common name for the pines in this subsection is pinyon pines. They predominantly grow in southwestern North America.

Most of the species yield a variety of edible pine nuts. These used to be a staple food for resident Native American tribes. They have now become a predominant ingredient in New Mexican food. Pinyon wood also has a distinctive fragrance, particularly when burned.

2.2.3.1 Mexican Pinyon (P. cembroides)

The Mexican Pinyon or the Mexican Nut Pine is native to western North America. It grows in areas with low annual precipitation. It is a small pine species, growing up to a maximum of 66 feet (20 m) tall.

The seeds of the Mexican Pinyon make up a large part of the Abert’s squirrel’s diet and Mexican jay. They are also popular for human consumption. The Mexican Pinyon grows well in its extreme climate. Therefore, it has received a status of Least Concern.

2.2.3.2 Colorado Pinyon (P. edulis)

The Colorado Pinyon also goes by the names Two-Needle Pinyon and Pinyon Pine. In its ancestral line, it is the member of a Madro-Tertiary Geoflora. Those were a group of highly drought-resistant trees in the United States. That explains their capability to thrive in desert areas of southwestern America.

The Colorado Pinyon Pine is another small pine specimen, only reaching 10 to 20 feet (3 to 6.1 m) tall. It is another aromatic species. You can even extract essential oils from almost every part of the pine. The Pinyon Jay effectively spreads the seeds of this tree. It is a Least Concern species.

2.2.3.3 Weeping Pinyon (P. pinceana)

The Weeping Pinyon is another pinyon but less common than the others on this list. Regardless, it is still a Least Concern species. Its distribution throughout Mexico covers more than 470 miles (750 km) from north to south. It often has more of a shrub shape than a tree.

2.2.3.4 Big-Cone Pinyon (P. maximartinezii)

The Big-Cone Pinyon is currently the only endangered pinyon. It also goes by the name Martinez Pinyon. It is native to western and central Mexico. Since it has such a localized range, it is highly susceptible to deforestation and climate change.

The small tree has brown bark with deep fissures at its base. Its needles are a light blue-green color and quite soft. Due to its remote range, it wasn’t discovered until 1964. Even then, it was only because a Mexican botanist noticed the sale of unusually large pine nuts in the local villages around the tree’s range.