Trout is one of the most sought-after freshwater fish in the world. They happen to be incredibly fun to catch, taste great, and can adapt to survive in a wide array of habitats. Whether you’re out at sea, floating down a river, or cruising around a lake, there’s probably a non-native trout species in the water.

Salmon, char, and true trout are all very similar genetically, so similar in fact that many fish species we consider trout aren’t trout at all. We’ll be discussing the 12 trout species you should know about, explaining what a trout even is, and talking about the major impact on ecosystems trout have had around the world.

You May Also Like: What Is Fly Fishing?

What Is A Trout?

Trout are fish that belong to a few specific scientific genera and families, including Oncorhynchus, Salmo, Salvelinus, Salmoninae, and Salmonidae. The term trout is also used to refer to some fish outside of the salmonid family that occurs in saltwater.

The confusion with the term trout really comes into play because the word “trout” isn’t a scientific classification. Rather, it’s typically used to refer to salmon-shaped fish, usually, those that are in freshwater environments. mWe’ll go more in-depth on the confusion around the name trout further on in the article.

True trout are closely related to salmon and char species, occasionally being mistaken for one of these fish. Some fish like the saltwater speckled trout aren’t trout at all and are instead part of the drum family.

One big thing to remember about trout is that they tend to be very adaptable and tend to have high survival rates when brought into new environments. North America hosts the most trout species in the world, but many were introduced from other regions.

Another important thing to keep in mind is that trout are very closely related, despite being differentiated by taxonomy or by name. Many common trout species are subspecies of a larger group or can interbreed with other trout strains. This can make explaining different species a much more complex topic than one would expect.

Trout tend to be apex predators in their natural stream environments, feeding on fish, insects, and crustaceans. They also play an important role in the greater ecosystem by serving as a food source for birds of prey, mammals, and larger fish in certain environments.

Share This Image On Your Site

You May Also Like: 20 Most Important Fish In Lake Michigan: Native And Introduced

The 12 Different Species of Trout in North America You Should Know About

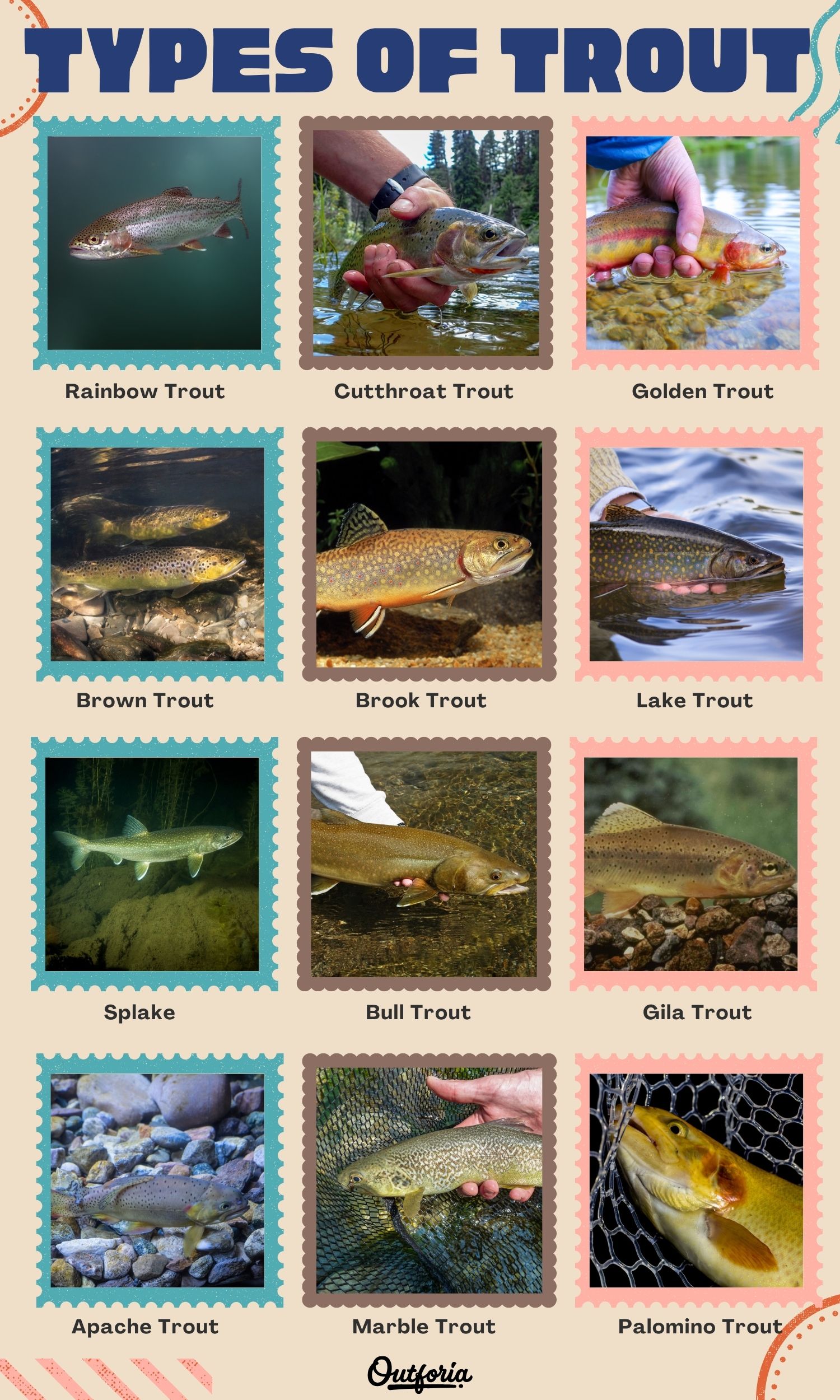

1. Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)

Rainbow trout grow to an average size between 20 and 30 inches (51-76 cm) and can weigh up to 8 pounds (3.6 kg). They’re best identified by the pink stripe on their side, but they also have black spots on their dorsal fins and a square tail.

These trout have a native range stretching along the Pacific coast of North America from Mexico to Alaska. Due to their popularity with anglers, they have been stocked in bodies of water around the world including the Great Lakes, the Southeastern United States, and Southern Canada. Rainbow trout can be found on every continent except Antarctica.

Rainbow trout have the ability to migrate to the sea and return to freshwater to spawn. The rainbow trout that can do this are called steelhead trout. There are a few variants of rainbow trout like this that are all essentially the same species but have slight differences due to their environments.

3. Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii)

Cutthroat trout are best identified by the red or orange coloring on the lower jaw and throat, as well as the small black dots along their back. The different populations and subspecies of cutthroat trout can range from 6 to 40 inches (15 to 102 cm) in length and weigh between 0.4 ounces (11 grams) to 41 lb (19 kg).

The fifteen subspecies of cutthroat trout are due to populations being isolated in tributaries for long periods and whether or not they have access to the sea.

These trout have a native range that extends across the western half of the United States, but have been introduced to the Northeastern US and can travel through the ocean as far north as Alaska.

3. Golden Trout (Oncorhynchus aguabonita)

Golden trout can best be identified by their golden sides and red, horizontal bands along their lateral line. In their native habitat, they typically reach lengths between 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm). In areas they have been introduced, they can grow much larger, sometimes reaching weights close to 11 pounds (5 kg).

They’re the state fish of California for a reason, as they are native to the Golden Trout Creek tributaries. While they have been transplanted into many lakes and river systems, most of the time they simply hybridized with rainbow or cutthroat trout.

Golden trout are considered threatened, as they are out-competed by other species of trout that have been introduced into their native waters.

4. Brown Trout (Salmo trutta)

Brown trout are best identified by their slender heads and reddish-brown bodies with black spots. Their size is naturally determined by the body of water they reside in, where trout in lakes grow much larger than trout in streams. At their largest, brown trout can grow to a length of 100 cm (39 in) and weigh up to 20 kg (44 lb).

Their native range is in Europe, specifically extending From Norway to Russia and from Iceland to Pakistan. Brown trout were heavily introduced into the Americas, Australia, Asia, and eastern regions of Africa as both a sportfish and a predator for population control efforts.

Many variations of brown trout are considered potamodromous, meaning they move from their homes in lakes to streams to spawn. There is also an anadromous line of brown trout that spend most of their time in the ocean and spawn in freshwater.

5. Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis)

Brook trout are best identified by their dark green or brown color and the distinct marbled pattern that appears on their backs. They reach lengths between 25 and 65 cm (9.8 to 25.6 in) and can weigh anywhere between 0.3 to 3 kg (0.66 to 6.61 lb).

The native range of brook trout includes the Northeastern regions of North America, spreading into the Appalachian regions of Georgia, North Carolina, and the Mississippi River. They’ve also been introduced into the western United States, Europe, South America, and Australia.

Introductions of brown and rainbow trout, as well as habitat loss, have seriously deflated their populations across the southern areas of their range, confining them to mountain streams at higher elevations.

6. Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush)

Lake trout are one of the largest trout species and are best identified by their brown color, white spots, and forked tail. Averages lengths for lake trout tend to be between 24–36 inches (61–91 centimeters), weighing between 15–40-pound (6.8–18.1-kilogram). The largest lake trout can reach weights close to 100 pounds (46 kg).

While lake trout are technically a char and not a “true trout,” they do belong to the Salvelinus genera and are considered trout. They also rightly have a spot on this list thanks to their prominence in the sportfishing community.

The natural range of lake trout includes Canada, Alaska, and the Northeastern United States. Like every trout on this list, they’ve been introduced into non-native waters around the world, including in Europe and South America.

7. Splake (Salvelinus namaycush)

Splake is a hybrid species that comes from crossing a male brook trout with a female lake trout. They tend to not reproduce effectively in the wild and are instead normally bred and introduced as a sportfish by wildlife management groups.

Splake average weights are between 2 pounds and 4 pounds (1-2 kg), but 20-pound (9 kg) specimens are not uncommon. As a hybrid, they don’t really have a native range, however, they were originally experimented with in an effort to help collapsing populations of trout in the Great Lakes.

8. Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus)

Bull trout get their name from their unusually large mouths and heads. They tend to it into one of two patterns, either migratory or non-migratory. Migratory bull trout grow much larger than resident (non-migratory) fish, reaching lengths up to 103 cm (41 in) and weights near 14.5 kg (32 lb).

These fish are considered to be extirpated from their native range in northern California and are listed as vulnerable in their other natural habitats that extend across the northwestern region of North America.

9. Gila Trout (Oncorhynchus gilae)

Gila Trout is one of the rarest trout species in the United States, native only to tributaries of the Gila River in Arizona and New Mexico. They’re best identified by their yellow body with brown spots. On average, they reach a length close to 30 cm (11.8 in).

Gila trout are closely related to both the rainbow trout and the Apache trout, though all three are “true” trout species. In addition to their limited range, they’re listed as endangered thanks in large part to competition from hybrid trout, the introduction of rainbow trout, and habitat loss.

10. Apache Trout (Oncorhynchus apache)

Apache trout are best identified by their golden bellies, dark head, and the appearance that they are wearing a mask over their eyes. They reach lengths between 6 to 24 in (15–61 cm) but are most commonly found at lengths under 10 in (25 cm).

The Apache trout is the state fish of Arizona and is native to the upper Salt River watershed and the upper Little Colorado watershed. They have been introduced to similar habitats around the Grand Canyon and the Pinaleno Mountains.

11. Marble Trout (Salmo marmoratus)

Marble trout are best identified by their massive heads and marble-patterned spots along their backs. Adults typically reach lengths between 12 and 27 inches (30–70 cm).

Their native range extends only to specific tributaries in Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro.

In some regions, this fish is considered extirpated, largely thanks to competition from introduced trout species and pollution.

12. Palomino Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita)

Also known as the golden rainbow trout, the palomino trout is one of the most popular trophy fish in the United States. The world record for this species weighed in at 13 pounds, 8 ounces.

The story behind the fish is that they are essentially just regular rainbow trout. One fish with a genetic mutation in a fish hatchery was bright yellow. Scientists studied the specimen and cross-bred this trait to produce self-sustaining populations of these golden rainbow trout in creeks throughout North America.

As a rainbow trout offshoot, their native range is along the Pacific Coast, however, you’ll find these palomino trout in West Virginia, the Great Lakes Region, and the Pacific Northwest today.

You May Also Like: 15 Florida Freshwater Fish: Photos And Facts

Clarifying The Confusion Surrounding “Trout”

Though we lightly discussed what was a “true trout” and the taxonomical classifications that were included, it’s worth discussing in more detail here. The word trout is used to refer to many, many, many fish that either isn’t trout at all, are closely related, or are hybrid species that have no natural populations.

Species of fish that fall into the Oncorhynchus, Salmo, Salvelinus, Salmoninae, and Salmonidae taxonomy groups can all be referred to as trout. Where this gets confusing is the fact that whether some species are trout, char, or salmon depends completely upon who you ask or where you get your information.

As an example, the Dolly Varden trout is listed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game as a char, not a trout. It does, however, belong to the Salvelinus genus that is considered the “true char.” This genus includes brook trout, lake trout, and bull trout and is one of the groups that can be considered “trouts.”

If it sounds like I’m beginning to talk in circles, that’s kind of the point. The term trout isn’t a scientific term and can refer to a wide range of salmonid species that may be considered trout, char, or salmon, all depending on who you ask.

The important thing to take away from this is that generalized terms don’t always provide a quick and simple explanation. Instead, as with the case of the word trout, they tend to complicate matters when it comes to identification and classification.

You May Also Like: 17 Different Types Of Catfish: Pictures, Facts, And Guide

Trout: Sportfishing, Conservation, and Introduction

Behind bass fishing, trout are one of the most popularly targeted freshwater species for sport fishermen. For years, they’ve proved to be a valuable natural resource as a food source, creating income through fishing, and been used as a population-control species.

The Impact of Sportfishing Most People Don’t Know About

Sportfishing, much like hunting, is the source of the vast majority of funds that go into wildlife management and conservation. While organizations do exist that donate to these programs, their contributions tend to be much smaller than what anglers end up bringing in.

This is the side of fishing that most people don’t see. Overfishing is a real problem and some people have ethical concerns in regard to both hunting and fishing.

In the United States, most wildlife management departments receive little to no funding from the government. Their sales of licenses, sometimes combined with equipment sales in stores, is where they bring in most of their money.

Wildlife management departments are the wonderful people who set up and maintain conservation zones, enforce harvest limits, collect population data, and implement programs that mitigate the impact of humans on ecosystems.

Without the work of these people and the outdoorsman that funds it, many ecosystems would be completely devastated. Sportfishing is a huge part of that, especially when it comes to trout and the health of American waterways.

In addition to funding the preservation of species, sportfishing brings in major economic boosts to communities on the water. It provides jobs for guides and brings tourists to an area.

The How Trout Populations Are Managed

Trout are managed differently around the globe, but the United States has some very intensive and specific management programs that are keeping both trout populations and larger ecosystems stable.

Perhaps the best example is to look at a Great Lakes Restoration program in the mid-1900s. While it is a complicated thing to describe, we’ll explain it as simply as possible.

The introduction of alewives, lampreys, and other invasive species to the Great Lakes through accidental releases and new channels from the ocean brought in new predators and quite a lot of competition for native species. These fish also had to contend with massive overfishing and pollution.

In order to revitalize the ecosystem, it was decided to introduce salmonid species including a few salmon and trouts. These fish would eventually make the Great Lakes a premier freshwater fishing destination and reduce populations of smaller invasive fish.

One problem wildlife managers ran into was that many of these introduced species had a hard time reproducing in the lakes. Either they wouldn’t spawn or the young fish died because of water temperatures.

To combat this, eggs were regularly collected and raised in hatcheries. Once the juveniles had grown enough, they were released into the lakes and tributaries. This practice is continued to this day, with millions of trout, salmon, and other fish released by state governments every year.

In addition to the great lakes, trout lakes were established. The management of these much smaller lakes is entirely devoted to the trout wildlife managers introduced to them.

Around the country, suffering populations of native trout have either very limited fishing seasons or are illegal to fish for altogether. This alleviates some of the pressure added to them by non-native trout species.

For the most part, wildlife management programs try to balance introducing trout to new regions and calculating the possible damage they will do to native species.

In the case of the Great Lakes, the introduction of trout is vastly considered a huge success, while in the southwest, it seems that native species are simply out-competed.

Trout Introduction Projects: Good, Bad, or Something in Between?

Due to their sportfishing popularity, trout have been introduced to waterways worldwide. Some regions have seen good results and a more diversified ecosystem, while others have seen populations of native species suffer.

The important thing to remember about introducing new species to an ecosystem is that the ecosystem is going to fundamentally change because of its presence.

The Great Lakes saw a lot of success thanks to the introduction of trout species. Alewife and other populations of problem species were brought under control. The ecosystem began to diversify thanks to the constant restocking of salmonids and the economies around the lake got a major uplift.

Other regions like the Southwestern United States saw their populations of Apache and Gila trout suffer. Larger, introduced species preyed on these smaller trout and out-competed them for resources in their rivers.

Trying to judge whether the introduction of trout is “good,” must be done on a case-by-case basis. Each project has different goals and will have unforeseen consequences.

Historically, you can find plenty of cases where introducing a new species was devastating for an ecosystem. From mongooses ending up in Hawaii to monkeys making their way to Florida, it’s easy to point out the failures that have plagued intentionally introducing animals.

On the other hand, there are success stories to be proud of. Peacock bass have done wonders for reducing exotic fish species in Florida’s canals and beavers reintroduced to Yellowstone saved their rivers.

The truth is that these projects tend to have better success rates when an ecosystem is already near destruction and proper research has been done beforehand.

Not all non-native species end up being a bad thing, but it takes time to determine the full impact of their introduction.