They may not be able to fly, but you can’t deny that penguins are awesome. These adorable flightless birds are skilled swimmers and incredible survivalists that can thrive in some of the world’s harshest environments.

But how much do you really know about the wonderful world of penguins? Have you ever wanted to learn about the different types of penguins that waddle and swim their ways across the planet?

If so, you’ve come to the right place. We’ll introduce you to the 19 different types of penguins. We’ll discuss what makes each species unique and offer up some cool fun facts so you can impress your friends and family with your penguin know-how.

All 19 Amazing Types of Penguin Breeds

Share This Image On Your Site

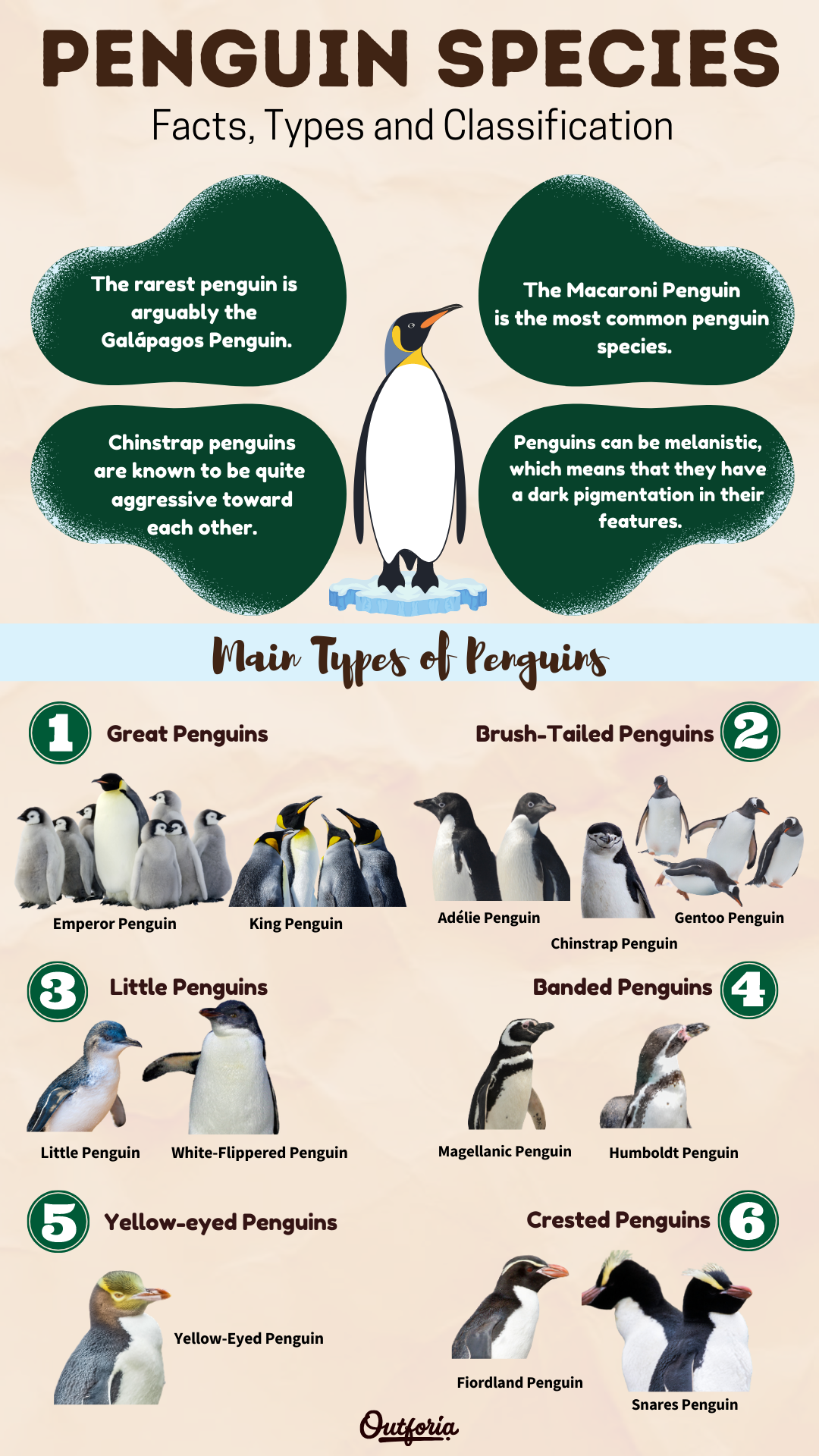

<a href="https://outforia.com/types-of-penguins/"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Types-of-penguins-infographic-1-1121.png"></a><br>Types of Penguins Infographic by <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>Although we commonly think of penguins that live only on the frigid ice-covered shores of Antarctica, there are actually many kinds of penguins, each of which inhabits a unique ecosystem on our planet.

There’s some debate among researchers as to how many penguin species there actually are. Depending on who you ask, you might be told that there’s anywhere from 17 to 21 species of these flightless birds.

To keep things simple, we’ll focus on the 19 most widely accepted types of penguins that roam the Earth. So, without further ado, let’s meet these cute and cuddly birds!

1. Genus Aptendoytes (Great Penguins)

Also known as the great penguins, the two species in the genus Aptendoytes are the biggest penguins on the planet. Here’s what you need to know.

1.1 Emperor Penguin

The world’s tallest penguin, the emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) is a truly massive bird that lives solely in Antarctica. In fact, the emperor penguin can be up to 39 inches (100 cm) tall and weigh nearly 100 lbs (49 kg), so there’s no doubt that this is one big bird.

Emperor penguins live primarily on the stable pack ice of Antarctica, though you can sometimes find them on solid land. The species creates breeding colonies that can have thousands of individuals that band together to raise their young.

The mating rituals and life cycles of the emperor penguin are well-documented in films like March of the Penguins. Each parent takes a turn incubating the egg for up to two months at a time while the other waddles back to the ocean to feed. Eventually, a young emperor penguin chick will hatch, chrèche, and then fledge into the sea before the start of the next winter season.

Since they rely so much on the Antarctic sea ice for food and shelter, emperor penguins are particularly susceptible to the effects of climate change. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the emperor penguin as near threatened as a result of this habitat loss.

1.2 King Penguin

While the emperor penguin might be one of the best-known penguin species, its close cousin, the king penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus), is no less spectacular. The king penguin is slightly smaller than the emperor with a maximum height of about 39 inches (100 cm) and a maximum weight of about 40 lbs (18 kg).

Physically, the king and emperor penguins look a lot alike. However, king penguins have much more silver in the feathers around their necks and backs. Additionally, king penguin chicks are a near-solid brown in color when they hatch while emperor penguin chicks have silver heads with black and white bodies.

It’s also easy to tell the king and emperor penguins apart in the wild because they don’t live in the same regions. Emperor penguins are true Antarctic birds while king penguins live on South Georgia, the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), Tierra del Fuego, and other sub-Antarctic Islands. They do not live in Antarctica proper.

The coolest thing about king penguins is that they live in massive breeding colonies that can have hundreds of thousands of breeding pairs. King penguins also have the longest breeding cycle of any penguin species. Young king penguins don’t fledge until they are about 14 to 16 months old, so you will see chicks in a king penguin colony all year long.

2. Genus Pygoscelis (Brush-Tailed Penguins)

The genus Pygoscelis contains the 3 species that are collectively known as the brush-tailed penguins. They all share a characteristically long set of tail feathers, but their unique feather patterns make them easy to tell apart. Let’s take a look at these incredible birds.

2.1 Adélie Penguin

Named after the wife of French sailor Jules Dumont d’Urville, Adèle, the Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) is the smallest of the three members of the genus Pygoscelis. Adélie penguins are the most widely distributed and the most southerly penguins on the planet.

The Adélie penguin boasts a characteristic all-black head, white stomach, and light pink feet, giving them a classic tuxedo look. Plus, these penguins have a distinct white ring around their eyes that makes it easy to distinguish them from their Antarctic neighbors.

As is the case with all Pygoscelis penguins, the Adélie feeds primarily on Antarctic krill, but they’re also known to eat Antarctic silverfish and glacial squid. Their primary predators are leopard seals, though Adélie chicks and eggs are often eaten by south polar skuas.

Due to their wide distribution, Adélie penguins are listed as a species of least concern by the IUCN and their population numbers may actually be on the rise. However, they are still at risk in the long term due to overfishing and the effects of climate change.

2.2 Chinstrap Penguin

Aptly named, the chinstrap penguin (Pygoscelis antarctica) is a small flightless bird with a distinctive black line of feathers under its chin that looks suspiciously like a chinstrap of a helmet. The chinstrap is found primarily in Antarctica, but there are breeding colonies located as far north as the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas).

Like the other members of the Pygoscelis genus, the chinstrap forms large breeding colonies each year. They nest exclusively on rocky and sandy areas where they can build a circular nest out of small stones. Young chinstrap penguins are absolutely adorable and they look like little gray puffballs until they experience their first molt.

Chinstraps have a reputation for being boisterous and aggressive. They also make a characteristic noise that sounds surprisingly like a mix between a donkey braying and a squawking gull. Check out this fantastic footage of chinstrap penguins in their native habitat to learn more:

The IUCN currently lists chinstrap penguins as a species of least concern, but their population numbers are decreasing. Habitat loss isn’t a major issue for these penguins as they nest on land, but the changing climate could wreak havoc on the Southern Ocean and disrupt the chinstrap’s primary food source—Antarctic krill—in the long term.

2.3 Gentoo Penguin

Our personal favorite penguin (don’t tell the others!), the gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua) is a large flightless bird that lives in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic regions. There are technically 2 subspecies of gentoo that are split geographically, but recent research suggests that there may actually be 4 subspecies.

When compared to other members of its genus, the gentoo is easy to identify because it has a reddish/orange beak, white stomach, and a black head. The gentoo also has a white band around its head that makes it look like it’s wearing a pair of white headphones.

The gentoo is actually the third-largest penguin, after the emperor and king. They live in large breeding colonies in either rocky, sandy, or grassy locales. While adult gentoos are cute, their young chicks are unbelievably precious, especially when they start learning to waddle around on their own.

Gentoos almost exclusively eat Antarctic krill, and you’ll often see large rafts of gentoos swimming around close to shore during the summer months. As a whole, the gentoo is listed as a species of least concern, but it faces many of the same threats as the other members of its genus.

3. Genus Eudyptula (Little Penguins)

If you’re looking for birds that are out-of-this-world cute, the two members of the genus Eudyptula are your go-to. Also called the little penguins, these two birds are astonishingly tiny. Here’s what you need to know about these fascinating penguins.

3.1 Little Penguin

The world’s smallest penguin, the appropriately named little penguin (Eudyptula minor) is a tiny flightless bird that lives in New Zealand and southern Australia.

Due to its slate-blue plumage color, the little penguin is sometimes called the blue penguin, particularly in New Zealand. Adult little penguins are normally no more than 13 inches (33 cm) tall and they usually weigh around 3.3 lbs (1.5 kg).

These penguins primarily live in small colonies in rocky and grassy areas where they can make nests. In sandy environments, the little penguin is known to burrow and dig a nest, too. In rare cases, these penguins will share their burrows and nests with other bird species.

Due to their small size, little penguins are hunted by a wide variety of predators, including various lizards, snakes, seals, and even Tasmanian devils. They were also hunted for sport during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Nowadays, the species is heavily protected in most regions and it is listed as a species of least concern.

3.2 White-Flippered Penguin

The white-flippered penguin (Eudyptula albosignata) is a recently-identified penguin that’s the subject of much dispute in the taxonomic community. It is very closely related to the little penguin and some taxonomists believe it to be a subspecies rather than a species in its own right.

Nevertheless, the white-flippered penguin features a distinct plumage coloration that’s mostly gray, rather than blue. It also has a white stripe on both flippers, hence the name.

Although it shares a similar range with little penguins, the white-flippered penguin only nests on Motunau Island and the Banks Peninsula near the city of Christchurch on New Zealand’s South Island.

The white-flippered penguin is mostly nocturnal, making it one of the only penguin species that’s mostly active at night. This makes the species difficult to observe in the wild, as they’re often burrowing in their nests when human researchers visit their colonies.

4. Genus Spheniscus (Banded Penguins)

Next up on our list, we have the so-called banded penguins of the genus Spheniscus. These fantastic birds all feature similar striped patterns on their faces and bodies and they make very loud noises that sound like a braying donkey. This is what you need to know.

4.1 Magellanic Penguin

The Magellanic penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) is a relatively small banded penguin that lives around the coastal areas of southern South America. It mostly lives in Patagonia and around the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), but you can sometimes see vagrants as far north as Brazil and as far south as Antarctica.

Of all the banded penguin species, the Magellanic penguins are easily the most populous. They generally travel in huge flocks and they form densely-packed colonies in bushes or borrows during the nesting season.

It can be very difficult to tell the Magellanic and Humboldt penguins apart, especially on the western coast of South America where their ranges overlap. However, there are two white bands of feathers around the neck of a Magellanic penguin while there’s just one white band on the neck of a Humboldt penguin. This is one of the only ways to tell the species apart in the wild.

Conservation-wise, the IUCN lists the Magellanic penguin as a species of least concern. But the species’ population numbers are declining mostly due to habitat loss, the effects of oil spills, infectious diseases, and climate change.

4.2 Humboldt Penguin

Found only on the Pacific Coast of South America, the Humboldt penguin (Spheniscus humboldti) is a medium-sized flightless bird that thrives in the cold waters of the Humboldt Current. It is closely related to the Magellanic penguin, but there are no breeding colonies of Humboldts located on the eastern coast of South America.

Humboldt penguins are skilled predators that feed on schools of pelagic fish. They prefer to eat Atlantic saury, Araucanian herring, silver-sided weedfish, and various anchovies. Most Humboldts forage near their colonies, however, they occasionally swim a few hundred miles from shore to search for food.

The Humboldt penguin faces a number of threats that are unique to its Pacific Coast habitat. In particular, El Niño–La Niña variations can have a major impact on Humboldt penguins. The suppression of the upwelling of nutrient-rich waters off the coast of South America during strong El Niños can cause a massive decrease in food availability for these penguins.

Humboldts also seem to be very sensitive to human presence. The introduction of invasive species, such as feral goats, can also destroy vegetation that these penguins use for nesting. As a result, the Humboldt penguin is currently listed as vulnerable by the IUCN.

4.3 Galápagos Penguin

The northernmost penguin species on the planet, the Galápagos penguin (Spheniscus mendiculus) is a small, but easily identifiable bird that’s closely related to its Magellanic and Humboldt neighbors.

Galápagos penguins are found primarily on Isabela Island and Fernandina Island where the colder waters of the Humboldt and Cromwell currents bring plentiful nutrients and food to otherwise tropical waters. Since Isabela Island is located on the Equator, the Galápagos penguin is the only penguin found in the Northern Hemisphere.

The Galápagaos penguin is the only tropical penguin species. As a result, the species has developed a number of unique adaptations to stay cool, despite its thick plumage and blubber. They’re often spotted panting at their nests in an attempt to cool off in the harsh tropical sun.

Interestingly, Galápagos penguins are one of the few truly monogamous penguins that form breeding pairs for life. There are fewer than 1,000 breeding pairs left in the wild and the species is considered to be endangered with a declining population.

4.4 African Penguin

The only penguin that breeds on the African mainland, the African penguin (Spheniscus demersus) is a funky-looking bird with a distinctively vocal personality. Also known as the jackass penguin, the African penguin frequently makes a noise that closely resembles that of a donkey.

These penguins are found throughout the southwestern coast of Africa, mostly in South Africa and Namibia. Since they’re the only penguins on the African continent, it’s impossible to confuse them in the wild with other species. Furthermore, African penguins have large pink glands above their eyes that make them easy to identify, even in photos.

African penguins are accomplished hunters that forage on large schools of fish, such as anchovies and sardines. They breed almost exclusively on a few dozen islands off the southwest coast of Africa, but there are a few colonies on the mainland, including at Boulders beach near Cape Town.

The African penguin is listed as endangered with a declining population. There are approximately 40,000 mature adults left in the wild. The species’ biggest threats include human disturbances, oil spills, invasive species, pollution, and the impacts of climate change.

5. Genus Megadyptes (Yellow-Eyed Penguins)

The genus Megadyptes contains just one living penguin species. There are at least two extinct species of Megadyptes penguins, but only the yellow-eyed penguin still waddles around this Earth.

5.1 Yellow-Eyed Penguin

The sole recognized living species in the genus Megadyptes, the yellow-eyed penguin (Megadyptes antipodes) is a truly stunning bird that only lives in southeastern New Zealand. Until fairly recently, the yellow-eyed penguin was classified alongside the little penguins, but genetic analyses suggest that they aren’t closely related.

Also known as the tarakaka or the hoiho, the yellow-eyed penguin lives in a number of small colonies on Stewart Island as well as the Auckland Islands, Campbell Islands, and the Otago Peninsula.

From a distance, the yellow-eyed penguin looks a bit like the gentoo, thanks to the yellow band that wraps around its head. However, the two species don’t overlap in range, so they’re impossible to misidentify in the wild.

The yellow-eyed penguin is listed as endangered with a decreasing population. There are fewer than 3,000–4,000 mature individuals left in the wild, making it one of the rarest penguin species. Its primary threats include disease, habitat degradation, introduced predators, and the impacts of climate change.

6. Genus Eudyptes (Crested Penguins)

Finally, we have the genus Eudyptes, which includes all of the penguins that are commonly referred to as the crested penguins.

Identifying each of these species can be a challenge because they all share a characteristic band of tufted yellow crests near their eyes. However, a keen attention to detail can help you become a whiz at identifying crested penguins. Let’s take a closer look at these wonderful birds.

6.1 Fiordland Penguin

The Fiordland penguin (Eudyptes pachyrhynchus) is a medium-sized crested penguin that’s found only in New Zealand. In te reo Māori, the Fiordland penguin is called tawaki or pokotiwha. It is also called the New Zealand crested penguin because its natural range extends beyond the region of Fiordland.

Like all crested penguins, the Fiordland penguin has yellow feathers that extend backward above its eyes. It’s mostly blueish-black in color, except for its white stomach and orange bill. But unlike the Snares and erect-crested penguins, the Fiordland doesn’t have bare pink skin around the edges of its bill.

Most Fiordland penguins live in small colonies that nest in very rocky areas along New Zealand’s southern coast. Before European colonization, their range also likely extended up to the southern part of the North Island.

The Fiordland penguin is now listed as near threatened with a declining population. Its primary threats include bycatch in commercial fishing operations. However, invasive species are another large problem. The species also seems to be very sensitive to human disturbance and oil spills.

6.2 Snares Penguin

Named after its primary breeding grounds, the Snares Islands, the Snares penguin (Eudyptes robustus) is a small crested penguin that’s known for living in fairly large colonies.

Only nesting on one island, the Snares penguin is generally easy to identify in the wild. But if a vagrant ends up on another New Zealand sub-Antarctic island, the best way to identify a Snares penguin is to look for the large patch of pink skin located at the base of its beak. Otherwise, it looks a lot like Fiordland and erect-crested penguins.

Snares Island, the species’ primary home, is a true gem of biodiversity in the South Pacific. Its dense foliage, rocky shores, and thriving fisheries allow Snares penguins to thrive in their natural habitat.

However, the Snares penguin is currently listed as vulnerable by the IUCN with a stable population. Its primary threats stem from overfishing in the waters surrounding Snares Island. Additionally, some researchers fear the accidental introduction of an invasive predator by tourist or research vessels, which would be disastrous for the species.

6.3 Erect-Crested Penguin

Another crested penguin found only in New Zealand, the erect-crested penguin (Eudyptes sclateri) is a poorly researched flightless bird that’s currently listed as endangered.

The erect-crested penguin breeds only on the Antipodes and Bounty islands, which are located off of the southeast coast of New Zealand. They generally establish colonies on large, rocky areas without other bird species, but you can sometimes see them nesting close to southern rockhopper penguins or even Salvin’s albatrosses.

Scientists don’t know much about the erect-crested penguin besides its breeding habits. They believe that the penguin feeds mostly on squid and krill, but more research is needed to really understand what the species does when it leaves shore.

It’s unclear why, but the global population of erect-crested penguins has been steadily decreasing since at least the mid-twentieth century. The erect-crested penguin is currently listed as endangered by the IUCN.

6.4 Southern Rockhopper Penguin

The southern rockhopper (Eudyptes chrysocome) is the southernmost of the two rockhopper penguin species. It lives mostly in sub-Antarctic waters and its range includes everything from southern South America to assorted islands in the southern Pacific and Indian oceans.

Southern rockhoppers are the smallest crested penguins with an average height of no more than 23 inches (58 cm) and a maximum weight of around 7.5 lbs (4.4 kg). They are difficult to distinguish from other rockhoppers, but the southern species normally has smaller yellow crest feathers.

Despite its wide range, the majority of southern rockhoppers live on the islands surrounding Patagonia and the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas). They mostly feed on krill, lantern fish, cuttlefish, squid, and crustaceans.

The IUCN lists southern rockhoppers as vulnerable with a decreasing population. Southern rockhoppers are primarily at threat from oil spills, human disturbances, and the effects of overfishing.

6.5 Northern Rockhopper Penguin

Northern rockhopper penguins (Eudyptes moseleyi) are small, crested, flightless birds that live primarily in the southern Atlantic and Indian oceans. Physically, the northern rockhoppers closely resemble the southern rockhopper penguins, however, genetic studies suggest that they are distinct species.

The majority of northern rockhoppers breed on Gough Island and Tristan da Cunha in the southern Atlantic Ocean. Northern rockhoppers form large colonies, mostly on rocky cliffs and beaches, however, the remoteness of their range makes them difficult to study.

According to the IUCN, the northern rockhopper is an endangered species with a declining population. Its primary threats include oil spills, overfishing, climate change, and introduced species, such as house mice.

6.6 Royal Penguin

Although not a great penguin like the king and emperor, the royal penguin (Eudyptes schlegeli) is certainly regal in its own right. The royal penguin is found only on Macquarie Island and its adjacent islands in the sub-Antarctic waters of New Zealand.

There’s some debate among researchers as to whether the royal penguin is actually just a macaroni penguin subspecies. But, even though interbreeding is possible between the two species, it’s not common. Royal penguins are also the easiest crested penguins to identify because the lower half of their face is white, rather than black.

These penguins live mostly on rocky slopes or beaches where they have good access to the sea. Royal penguins primarily eat krill, and individual colonies are known to have distinct fishing grounds. This peculiar behavior helps the royal penguin reduce intra-species competition, ensuring that all colonies can get enough to eat.

Unfortunately, despite its unique behaviors, the royal penguin is listed as near threatened. The species was hunted for oil throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. More recently, its major threats include oil spills, introduced diseases, and climate change.

6.7 Macaroni Penguin

Last but not least, we have the macaroni penguin (Eudyptes chrysolophus). Of all the crested penguins, it’s the most likely species that you might see if you venture to Antarctica as a tourist. However, its primary range is the sub-Antarctic Islands of the Atlantic and Indian oceans.

Macaroni penguins have a dark yellow crest that’s much more defined than what you see in most other crested penguin species. It’s also a bit larger than the other crested penguins in its range and it has a bulkier bill.

The IUCN lists the macaroni penguin as vulnerable with a decreasing population. But, it’s still found in massive colonies on islands such as South Georgia and in the South Orkney Islands, South Sandwich Islands, and Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) archipelagos.

Since macaroni penguins live in such dense colonies, they have a wide variety of vocalizations and funky nesting behaviors. Macaroni colonies also have low rates of predation by skuas and other birds of prey because there are simply so many adult birds packed into a small space in any given rookery.

How Are Penguins Classified

Although there’s quite a lot of debate over how many penguin species there are, classifying all of them isn’t too complicated.

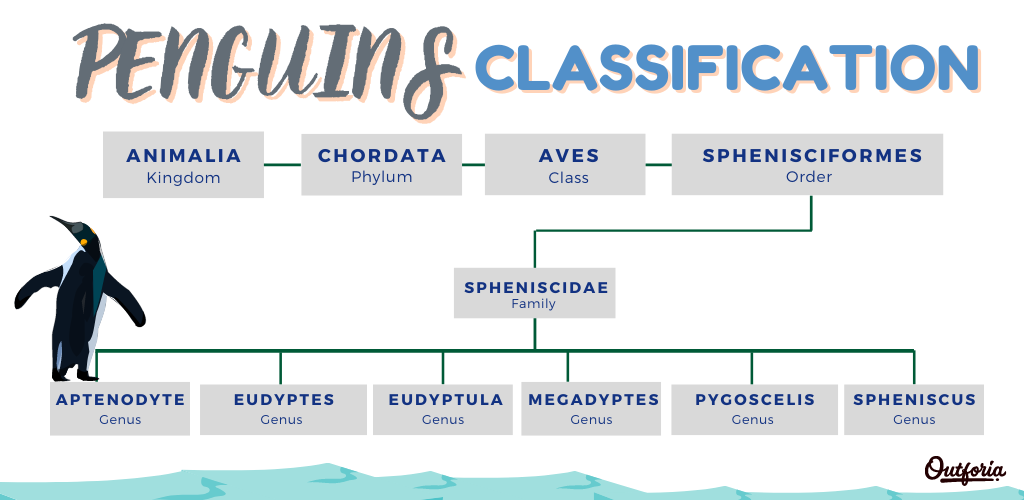

All penguins are members of the kingdom Animalia, the phylum Chordata, and the class Aves, the latter of which contains all the birds. Within the class Aves, penguins are part of the clade Austrodyptornithes.

This clade contains only the penguins (order Sphenisciformes) and a collection of birds known as the tube-nosed seabirds (order Procellariiformes). These tube-nosed seabirds, or tubenoses, as they’re called, include the petrels, storm petrels, shearwaters, and albatrosses.

Like penguins, these tubenoses all have a dedicated salt gland that lets them expel excess salt from their body. The penguins and tubenoses are all seabirds and they consume a lot of salt through their diet and from drinking saltwater. So, they frequently excrete extra salt from the glands near their beaks.

Getting back to the penguins, all penguin species are part of the order Sphenisciformes. Below this order, penguins are also all classified into the family Spheniscidae.

There are six genera of penguins with living species: Aptenodytes, Eudyptes, Eudyptula, Megadyptes, Pygoscelis, and Spheniscus. The species within each genus are grouped together primarily on the basis of genetic analyses. However, they usually share very similar physical traits, too.

Even though the taxonomy of penguins is fairly straightforward, researchers still debate how to classify some of these birds.

Most of these debates center on whether certain penguins are subspecies rather than species in their own right. For example, a few scientists believe the royal penguin is just a color morph of the macaroni penguin rather than a separate species.

But, these debates remind us that taxonomy is a work in progress and that we still have a lot to learn about these amazing birds.

You may also like: 30 Different Types That will Surely Impress: With Images, Classification, and More!

Penguin Fun Facts

Figure yourself an expert on all things penguin? Here are some super cool penguin fun facts to check out so you can impress your friends and family!

1| Penguins Are Well-Camouflaged

Penguins are well-known for their adorable tuxedo-colored plumage. But did you know that this fancy look is actually an important adaptation?

All penguins are seabirds, so they spend considerable time in the water hunting for food. Unfortunately, they’re also tasty prey for a number of species, including orcas and various types of seals.

To help protect them in the water, penguin species have evolved to have their distinctive ‘tuxedo’ look with white stomachs and black backs. As a result, predators swimming above penguins have a hard time seeing them in the darkness of the ocean. Meanwhile, predators swimming below penguins can’t tell them apart from the brightness of the sun above.

This adaptation is called countershading and it’s fairly common throughout the animal kingdom. You can see it in many types of sharks and in most dolphin species, too!

2| Penguins Only Live in the Southern Hemisphere

Okay, this fun fact isn’t entirely true, but hear us out.

All but one species of penguin lives exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. The only exception to this rule is the Galápagos penguin, which lives on two islands in the Galápagos. One of these islands, Isabela Island, straddles the equator. So, technically, the penguin lives in both the Southern and the Northern Hemispheres.

Other than that, there are no confirmed penguin breeding sites to the north of the equator. Therefore, despite what the movies might have you believe (we’re looking at you, Elf), polar bears—which live exclusively in the Arctic—and penguins don’t spend their free time together hanging out in the North Pole.

3| Not All Penguins Mate For Life

Even though there are some penguins that mate for life, the idea that all penguins are truly monogamous isn’t quite true.

Some species, such as the southern rockhopper and the Galápagos penguin are truly monogamous as they prefer to mate with the same pattern each breeding season.

But many penguin species are simply serially monogamous, which means that they have only one mate each year. This includes species like the emperor, gentoo, Adélie, and chinstrap, all of which may have different partners from one year to the next.

Sometimes, these serially monogamous penguins do return to the same mate year after year. But whether or not they do so depends on a lot of factors, such as if their last mating season was successful and if someone better has come along. What can we say? It’s a tough dating scene out there in the penguin world.

4| Penguins Are Skilled At Walking On Land

While their waddling might make you think that they’re not very comfortable on land, penguins are actually quite skilled at moving around on solid ground. Granted, they’re much more graceful in the water, but penguins are also well-adapted to their terrestrial habitat.

Penguins have a number of adaptations that help them master life on land. For example, their claws are very sharp, so they help them gain traction on icy surfaces.

During the spring, you’ll often see the Antarctic penguin species crafting small “highways” for themselves through the snow so that they can move easily from their nesting sites to the water. Penguins are also skilled at sliding around on their stomachs—something they can do to move quickly up or downhill.

Additionally, penguins waddle because they have short legs and very big feet. Researchers believe that this helps elevate a penguin’s center of mass away from cold surfaces, making it easier for them to conserve their body heat.

Oh, but keep in mind that, despite their waddle, penguins have knees! They’re just tucked behind a lot of fluffy feathers to help keep them warm in the cold.

Types of Penguins FAQs

Here are our answers to some of your most commonly asked questions about penguins:

How many types of penguins are there?

Researchers believe that there are anywhere from 17 to 21 different types of penguins. The most widely accepted number of penguins is 19. But more research is needed to determine whether certain penguin types are subspecies or species in their own right.

What is the rarest penguin?

The rarest penguin is arguably the Galápagos penguin. Researchers believe there are only 1,000 mating pairs of Galápagos penguins left in the wild. The yellow-eyed penguin is also very rare. There are approximately 2,000–3,000 mating pairs of yellow-eyed penguins left.

What’s the most common species of penguin?

The macaroni penguin is the most common penguin species. Numbers vary, but there may be as many as 20 million individual macaroni penguins in the wild. Another very common penguin species is the Adélie. Although they only live in the Antarctic, there are an estimated 10 million adult Adélies roaming around the White Continent.

What is the most aggressive penguin?

Penguins aren’t normally aggressive toward humans, but chinstrap penguins are known to be quite aggressive toward each other. They will fight over rocks to use in nest-building and they’ll even steal each other’s rocks when no one’s watching.

Are there any all-black penguins?

There are no penguins that have a natural all-black color morph without any other colors in their plumage. However, penguins can be melanistic, which means that they have a dark pigmentation in their features. When this happens, an individual penguin can have an all-black plumage.

How many types of penguins are there in Antarctica?

There are four species of penguin that are found on the continent of Antarctica: Adélie, chinstrap, emperor, and gentoo. Occasionally, vagrant macaroni and king penguins also show up in Antarctica, but they don’t have confirmed breeding sites on the continent. That said, there are some macaroni penguins with breeding sites on the islands near the Antarctic Peninsula.

What is a group of penguins called?

On land, a group of penguins is called a waddle, but in the water, a group of penguins is called a raft. Who knew?