Outforia Quicktake: Key Takeaways

- Mushrooms are the fruit of fungi, with around 14,000 species known as mushrooms; they come in various shapes and sizes, some edible and some poisonous.

- Identifying mushrooms involves examining their growth habits, caps, stalks, and spore surfaces, as well as color, bruising, and chemical reactions.

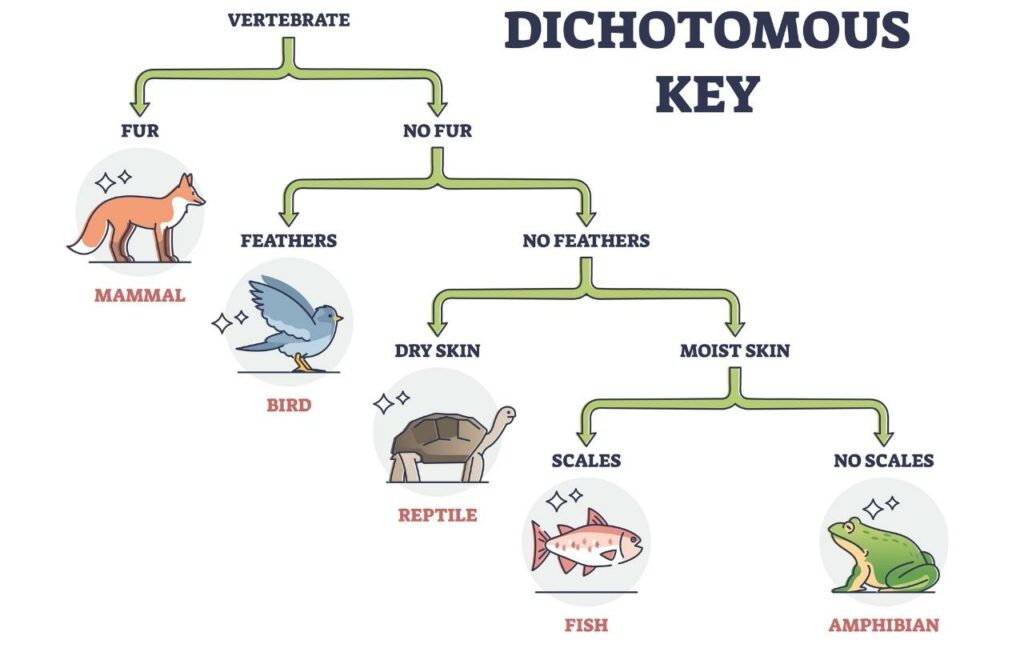

- Dichotomous keys are tools used to identify mushrooms by providing mutually exclusive answers, leading to a positive identification of the species.

- It is essential to exercise caution when identifying mushrooms, as some may be poisonous and cause adverse health effects if ingested.

Mushrooms are like inanimate insects. They live everywhere, have extraordinary diversity, and yet few acknowledge them. Some sprout as tiny cups after rain, and others are hollow balls of powder as large as your head.

The organism you see growing on trees or out of the ground is the fruit of the whole thing. The rest is a massive hidden web that makes plant life and decomposition successful.

You identify types of mushrooms by growth habits, caps, stalks, and spore surface. Besides shapes, you also use color, spores, bruising, and chemical reactions. Not all fit the shape that you may associate with the term “mushroom.” Some are edible, and others are poisonous.

In this guide, you’ll learn all the basics you need to identify mushrooms. The skill involves knowing the terms and anatomy of mushrooms. It also gets you to understand when different traits matter and how to use dichotomous keys.

What Are Mushrooms?

Mushrooms are fruits or sporophores of fungi. They are macroscopic or visible to the unaided eye. They produce spores when conditions are right for distribution. Around 14,000 fungi species are at least sometimes called mushrooms.

Sometimes the word “mushroom” will apply strictly to large, gilled varieties. Other times, it refers to culinary mushrooms.

The most familiar mushrooms look like umbrellas and come from the Basidiomycetes phylum. Specifically, they come from the genus Agaricus. They shed spores from the gills under their caps.

You know the chubbier mushrooms from grocery stores. And the lankier ones are common to yards, gardens, and forests after a good rain. But mushrooms take many forms.

Puffballs look like globes on short stems. Birds’ nests resemble tiny versions of their namesakes, and morels appear as elongated brains. There’s no shortage of diversity in the fungi world.

Structure and Terminology

When talking about mushrooms, knowing mushroom terms and anatomy helps. Anatomy will make you more skilled at sorting between types that look the same at first.

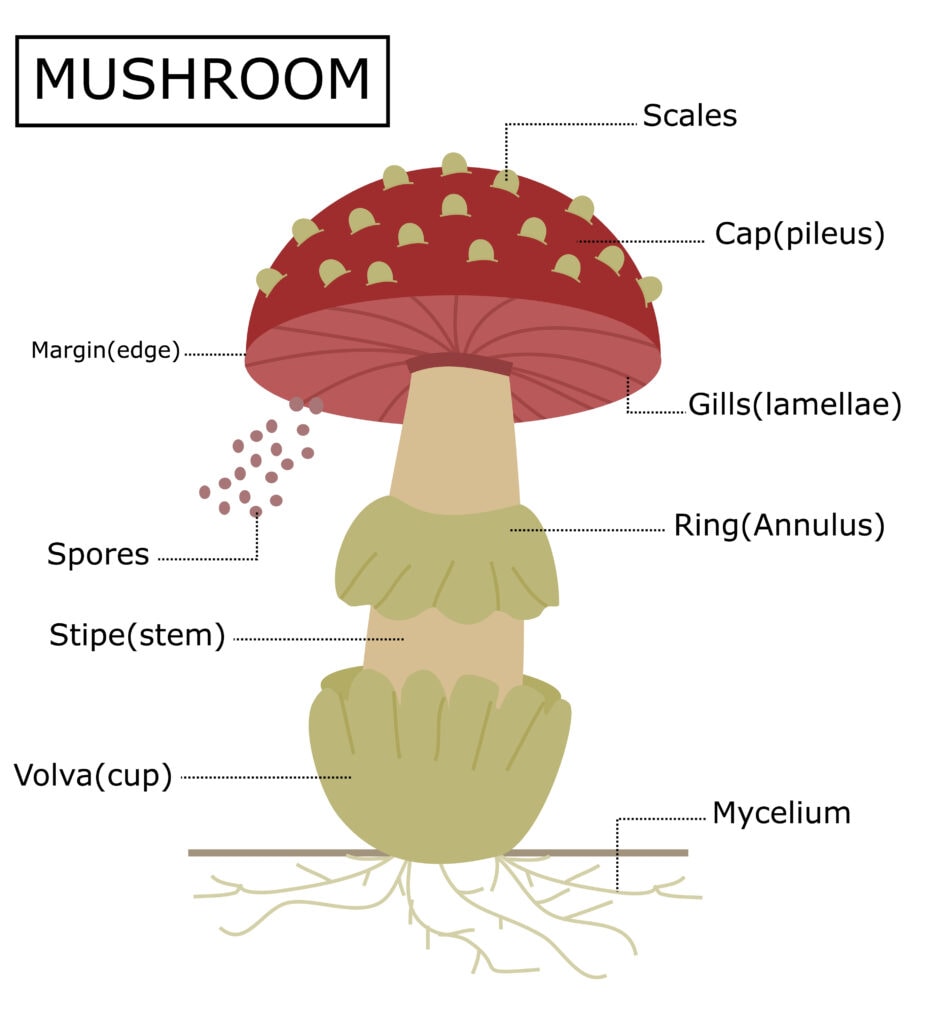

Your typical mushrooms, the Agarics, have a stem or stipe, a cap known as a pileus, and gills under the cap. Gills have several technical names a guidebook may use, including lamellae and sing. The spores get flung from microscopic club-like tissue in the gills.

The true body of the fungus is a thread-like network underground. The network is called mycelium or thallus. And the individual threads are called hyphae.

As the mushroom grows and forms its mature shape, it’ll have either a universal or partial veil. But at maturity, universal veils rupture and form stalk rings or annuli. Partial veils form warts on the cap.

How to Use a Dichotomous Key

Dichotomous keys are like a choose-your-own-adventure story. But you’re identifying something you found outside. They often use technical terms for parts of the mushroom, which is why vocabulary matters.

You start at Step One. It’ll give you two mutually exclusive answers. Based on your answer, you may read the name of the positively identified mushroom.

Otherwise, you’ll read a number. That number tells you which step to skip to next. Then you repeat the process until you get a positive identification.

How To Identify Mushrooms

When it comes to mushrooms, you can identify them in the field down to genus. Species often need more tools like microscopes and genetic testing.

In the field, you refer to physical traits. These include growth habit, cap, stem, spore surface, spores, veils, and their remnants. You also use color change from bruising or chemicals, habitat, and emergence timing.

Caution With Mushroom Identification

Mushrooms start as a pin-sized stage and expand into a button as they emerge from their substrate. They’ll take several shapes of bundled hyphae. These are often referred to as button and egg phases. Then they reach an iconic form you can use for identification.

For instance, field mushrooms will first appear as elongated bulbs with no stem. Then they form a globe on a stem, and finally, the ball opens into an umbrella. But also, if you wait too long, the umbrella will go farther upward until the mushroom is a long, ugly stick.

Over-aged mushrooms also stop producing spores. So you can’t sample the spores for identification.

Habit or Body Shape

A mushroom’s habit or body shape can include descriptions of its parts, like the cap and stock. But also, some mushrooms need more than that for you to identify them.

Mushrooms may have these other traits that defy typical descriptions:

- Ball: Some classic cap-and-stalk mushrooms have a ball-like cap that covers the stalk. But some mushrooms are truly a ball.

- Club: The mushroom is one solid post and often has a slightly narrower base compared to the tip.

- Vase: The entire length of the mushroom is vase-shaped.

- Rosette: Some mushrooms grow in massive, radiating clusters called rosettes. If you look from overhead, the shape looks like a rose.

- Bracket: The mushroom grows as a shelf on tree bark, lacking a conventional body.

- Tooth: These are a texture and a form. The mushroom may grow on a tree with obvious canine tooth-like extensions. It can also look like a stool of spongy material with teeth.

- Coral: These look like sea coral, but they are mushrooms growing on the land.

- Column: They grow as a column and taper near the end. They may also have many columns that may look like a man-eating plant from a horror film.

- Cup: Cup mushrooms resemble a suction cup on a stalk or a bird’s nest. Either way, they share the upper body being a cup shape.

- Jelly: These are a texture and a form. Jelly mushrooms can take many shapes from a bracket to ooze on the bark it’s growing on. But the texture will always be jelly.

For broader growing patterns, some mushrooms form rings, clusters, or scattered.

Caps: Shape, Color, and Texture

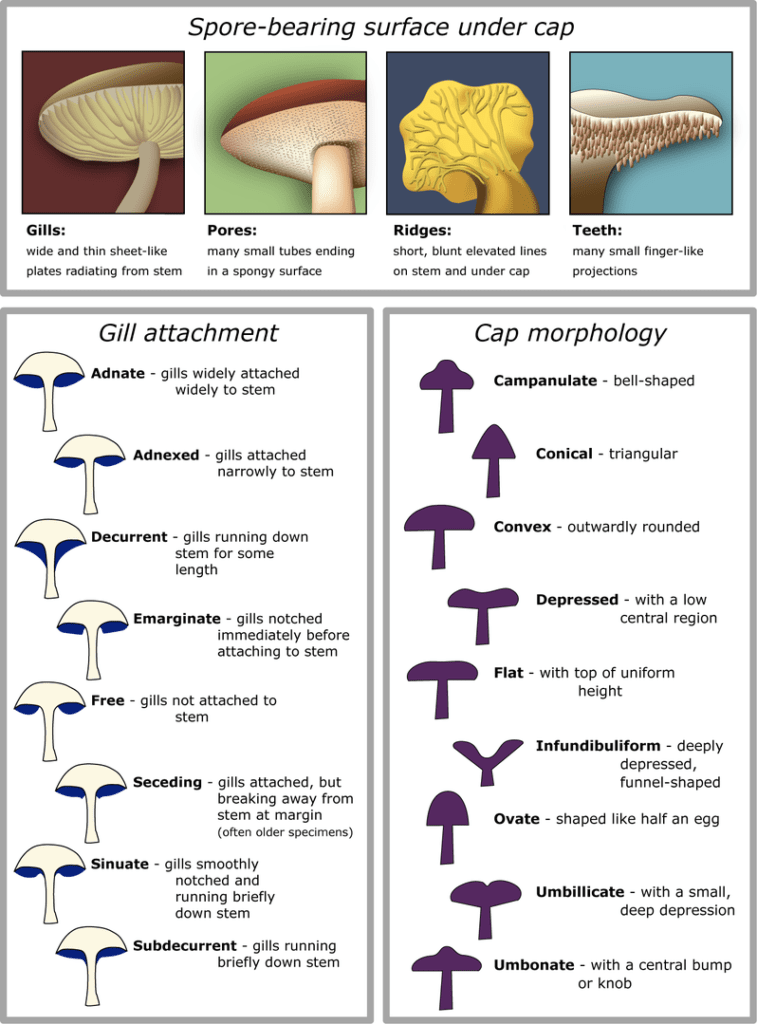

The first trait you’ll identify of a mushroom in the field is its cap shape when viewed from the side and the color. Mushrooms typically fall into one of nine categories.

Usually, field guides use the following terms and definitions for them:

- Campanulate: These are bell-shaped domes.

- Conical: The dome is dramatic enough to take a rounded triangle shape.

- Convex: Convex can almost be half globes with a broad, outward rounded shape.

- Depressed: Think about these caps like a well-used button with a low central region.

- Flat: Think of flat caps like tabs, which are level on top.

- Infundibuliform: These are caps with deeply depressed central regions. They may even be funnel-shaped.

- Ovate: Think of ovate caps like half an egg or a sharper convex shape.

- Umbilicate: Umbilicate caps don’t stand out except for the very center. There they have a small, deep depression. Thick of the dip as a belly button.

- Umbonate: Umbonate caps are nondescript, other than they have a central bump or knob.

When you try to identify a mushroom by its cap, also note its color and texture. Texture can be leathery, tough, slimy, or jelly-like.

Stems: Shape, Color, and Texture

Not all mushrooms have stems. Of the ones that do, the stalk may have a centered position in the cap or be off to one side.

The stem’s shape will also vary across mushroom genera. Stalks can be:

- Equal: The width of the stem is consistent throughout.

- Clavate: The base of the stem is wider than the end, creating a club shape.

- Ventricose: The middle of the stem is swollen, and the base and tip are narrow.

- Bulbous: The base of the stem is broad like an onion, while the rest of the stalk is consistent and narrow.

- Fusoid: The middle of the stem is subtly swollen on an otherwise narrow stalk.

- Radicating: The stem is long and narrow and continues into the ground for a while before tapering.

While you’re looking at the stalk, also note the color and texture.

Spore Surface: Texture

If you look under a mushroom’s cap, you’ll see one of these spore surface shapes:

- Gills: Gills have evenly dispersed sheets. They radiate from the stem to the outer rim of the underside of the cap.

- Ridges: Ridges look like gills, but the lines are thick and irregular.

- Pores: Pores look more like a sponge or skin. The underside will be one surface, but you see the divots that lead to tubes inside the tissue.

- Teeth: Teeth are protrusions from the cap. They resemble stalactite formations in caves or icicles from a roof eave.

Spore Surface: Gill Attachment

Identification goes further with mushrooms that have gills. Gill attachment is one of the most critical methods.

Attachment styles are clear if you slice a cross-section of the mushroom and include:

- Adnate: Where the gills attach, more tissue touches square to the stem. Think of it as the full length of a sheet of paper’s edge against the spine of a book.

- Adnexed: Where the gills attach, less tissue touches the stem. Think about it as the same sheet of paper’s edge, but the edge against the book spine has been cut in half.

- Decurrent: Decurrent gills curve gradually downward as it gets closer to the stem.

- Subdecurrent: Like decurrent, these curve downward. They attach a long way down the length of the stem. But they start the trajectory only once they’re close to the stem.

- Sinuate: Sinuate gills look like they could be free but swerve down the stem short ways down and then attach.

- Seceding: Seceding gills are like adnate or adnexed, but the attachment looks frayed.

- Emarginate/Notched: Emarginate gills are like adnate or adnexed but don’t attach to the stem. It’s like the gills got cut before touching the stem.

- Free: Free gills are like adnate or adnexed but don’t attach to the stem. Unlike emarginate, free gills don’t have a sudden cut. They look like they naturally don’t attach.

Be careful. The attachment type often changes during different phases of mushroom growth.

Spores

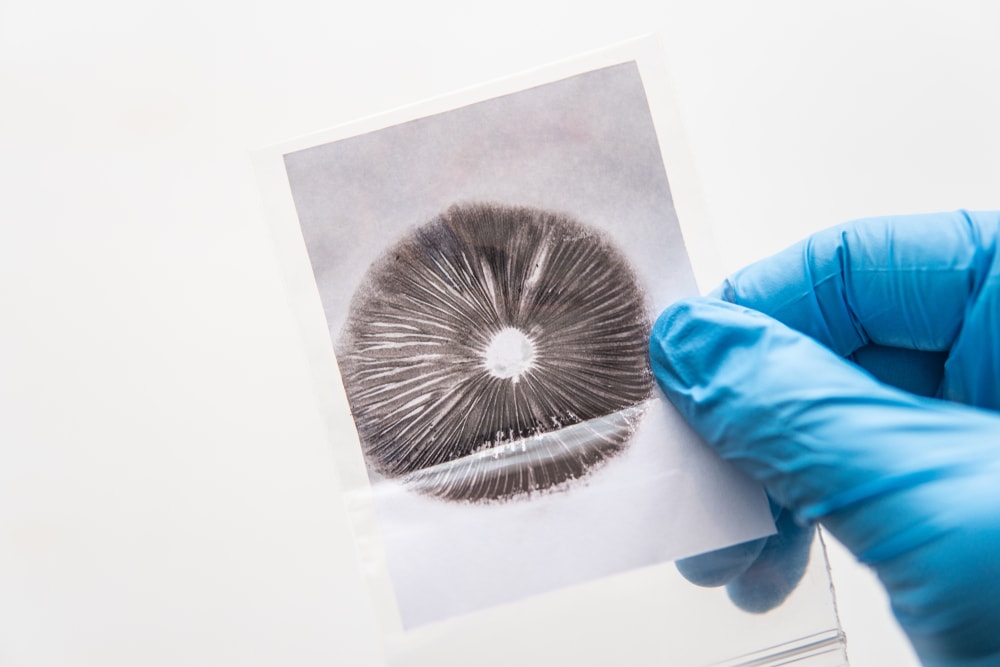

The microscopic trait most important to mushroom identification is the spores. Spores typically have a pin shape with one side elongated. That side embeds into the basidium like a follicle. The other side has a pore that germinates a hypha.

Despite being so small, you can use them in the field. The easiest way to identify spores is to create a spore print. These reveal gill patterns as well as spore colors.

Spore Prints

Spore prints are like human fingerprints and dental records. Every set of gills, pores, or spines is unique. They come in different colors, usually white, brown, black, yellow, purple, and pink. Puffballs, though, often have green and blue as well.

Check out this video on how to make spore prints:

- Create a surface for the print, like a white sheet of paper and a black one, or even aluminum foil.

- Tape the pieces side by side or partially overlapping.

- Cut the cap off the stem of a mature and healthy mushroom so that the cap can sit level.

- Place the cap with the gilled or pored side facing down, half on the white paper and half on black if that’s what you’re using.

- Cover the cap with a bowl or jar.

- Wait for several hours or up to 12 for the spores to fall and create a print.

- The print shows the lines of the gills where the spores came from and the spore color.

- If you used aluminum foil, you can fold the sides and seal your print for later use. With proper storage, it can be good for up to a year.

Spore prints also come with a risk of interpretation errors. Sometimes humidity interacts to discolor and move the print. Some mushrooms also exude liquid. That may get confused with environmental moisture on the paper.

Veils, Volvas, and Annuli

Some mushrooms will have remnant veils in the form of stem rings or patches on the cap.

As mushrooms push out of the substrate where their main bodies live, they take some of the hyphae with them. You don’t see the hyphae because a veil envelops them. The hyphae develop inside into a future mushroom, at which point the veil bursts.

Mature mushrooms keep remnants of these veils. And you can narrow down the identity by the form the remnants take.

Veils take two forms:

- Universal veil: Universal veils protect the entire mushroom while it grows. It breaks into a volva or cup at the base of the stem. It also leaves warts on the cap.

- Partial veil: Partial veils protect just the gills of the growing mushroom. It breaks into a skirt or collar around the middle of the stem. It’s also called an annulus or ring. It leaves warts on the edge of the cap or webbing called a cortina.

Color Change Tests

Mushrooms change color depending on physical and chemical tests you can do. One is bruising. If you rub or crush a mushroom cap or stem, it may bruise. The color of the bruising can help to identify the mushroom. Almost all boletes bruise blue, for example.

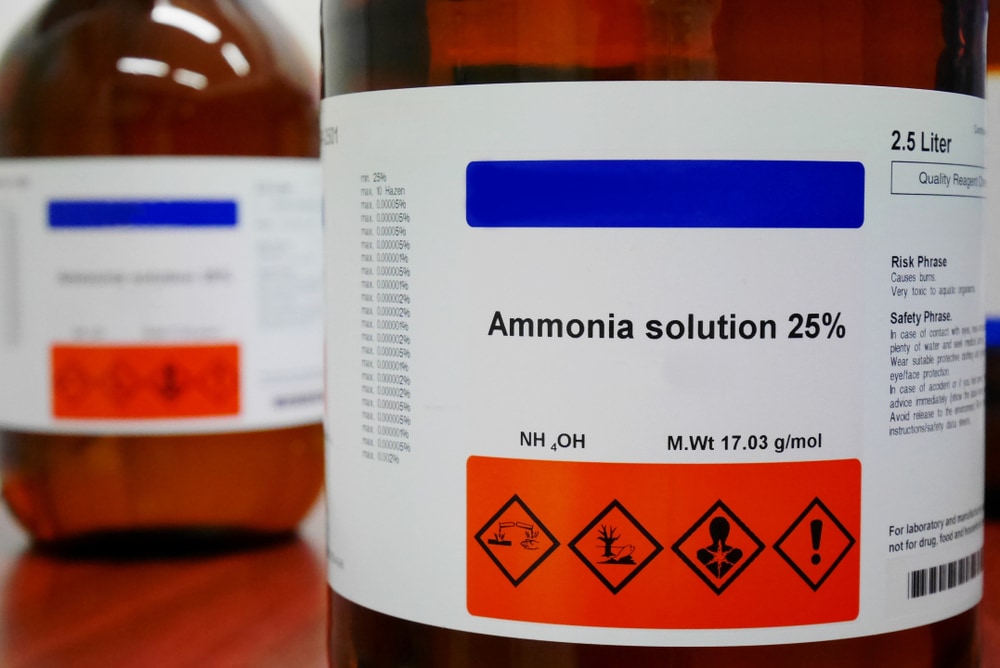

You can also buy three chemicals as a mushroom enthusiast to test on your specimens. No fancy scientific equipment, just ordinary means and materials.

The method:

- Leave one drip of the solution on the surface of the mushroom.

- Observe if any color changes. It can happen briefly to one color and longer to another, or once to a permanent change.

Chemicals For Tests

You can use common household ammonia (NH4OH) to identify fresh bolete mushrooms.

You can also use potassium hydroxide (KOH) as a 3–10 percent aqueous solution. It works on boletes, polypores, and other gilled mushrooms.

KOH is helpful for poisonous mushrooms. They turn yellow for some Amanitas. Dark pink and olive green may happen with Russula and Lactarius.

Another option is iron salts (FeSO4) in a 10 percent aqueous solution for boletes and russulas. For russulas, iron salts work better to place the drop on the stem than on another body part.

A lack of color change can also inform your identification process.

Location and Habitat

Many mushrooms will grow all over the northern hemisphere in many ecosystems. But they still have a habitat preference. Mushrooms value substrate.

If they grow in the soil, they’ll grow in soil elsewhere. If they need tree bark, they’ll grow on tree bark elsewhere. Some mycotrophs even grow on and eat other mushrooms.

Different genera or species of mushrooms might have narrower preferences. Many fungi are mycorrhizal. When they enter a relationship with a plant, it can be with a specific type of plant or several.

These are the ecosystems that matter to mushrooms. If you know what species of tree or type of soil they like, then you know where to look for the mushroom.

Timing

Once a spore lodges in its new substrate, hyphae germinate and get deep into the ground, manure, or bark. There, they form massive, dense webs. The new mushrooms form at the edge of the main hyphae webs. The edge expands over the years.

Mushrooms often start to sprout overnight. They also emerge fast after rain or disappear the next afternoon or when the rain begins.

When you observe where these mushrooms sprout, you can check again in the same season or weather.

You may also like: 43 Different Types Of Mushrooms: From Edible To Poisonous (Pictures And Chart)

Edible Mushrooms and Their Nutrition

A popular reason to identify mushrooms is to know which ones are edible. The most cultivated mushroom in the world is the Agaricus bisporus. This mushroom grows on farms but is also native in European and American fields and is white or brown.

In a store, you would find many names for mushrooms. For instance, the common, champignon, portobello, and Swiss brown mushrooms. These are cultivars or cultivated varieties of the same species.

You can find other species native in the northern hemisphere wilds and in grocery stores. They include the tooth fungus Hericium erinaceus, shiitake, hen-of-the-woods, and oyster mushrooms.

Nutrition

Edible mushrooms have a diverse nutrition pallet. Even though mushrooms are 90 percent water, the rest has nutrients.

They are 5 percent carbohydrates, 3 percent proteins, and 1 percent fat. The last 1 percent has electrolytes and minerals like potassium, phosphorus, and zinc. Vitamins include many of the B.

Not to mention that mushroom enthusiasts love the flavor and texture.

You may also like: Aloe Gone Wrong: Does Aloe Vera Gel Expire?

Poisonous Mushrooms and What Makes Them Poisonous

Close to 80 species of mushrooms are poisonous to humans. Many of these species contain alkaloids, particularly muscarine.

The fly agaric, Amanita muscaria, is the most infamous of toadstools. It can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, breathing issues, pupil dilation, and confusion. The symptoms start several hours after eating the mushroom and can last for 12 hours.

Another is the death cap, Agaric phalloides. It contains peptide toxins that survive cooking and destroy cells. In 6–12 hours after ingestion, it causes stomach pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. It can also create complications with the liver, kidneys, and central nervous system.

Blood sugar can drop enough to trigger a coma and a 50 percent death rate.

Uses for Poisonous Mushrooms

Some mushrooms have compounds like psilocybin and muscimol. Those are toxic, medicinal, or psychoactive. People have used them in traditional rituals to treat illnesses and recreational experiences.

Scientists are studying mushrooms for addiction, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and migraine treatment. Medical professionals also use extracts from mushrooms for cancer therapy in some countries.

You may also like: Toxic Plants That Look Like Food: 30 Plants You Need To Know

How To Safely Identify Mushrooms

There are no traits to decipher if a mushroom is edible or toxic. Until you get experienced with identifying mushrooms, you have resources to help you.

👉🏼 Find a Mentor

Nothing compares to learning with a mentor when identifying mushrooms in the field. You can look up mushrooming groups in your local area. Often university extension services and cultural or nature centers have them.

You may even find a well-established Meetup or Facebook group that does outings. Experienced mushroom hunters and newcomers alike attend.

👉🏼 Field Guides

Your next best resource to stay safe with your mushrooming is to own a good field guidebook. Some will have dichotomous keys. These take you step-by-step through individual traits until you find the exact mushroom. Other books have excellent photos and descriptions.

👉🏼 Know a Few Rules

Besides good resources, the least you need to do to safely identify mushrooms is to:

- Never eat one you aren’t 100 percent certain about.

- Use gloves when handling mushrooms in case it’s a species that has toxic chemicals your skin can absorb.

- If you eat your samples, cook them first.

- If you eat your samples, try a small amount.

- If you didn’t use gloves or eat your samples, wait 24 hours before handling or eating again.

Some people have allergic reactions to edible mushrooms. The common mushroom in the grocery store, Agaricus bisporus, contains hydrazines. But the molecules break down during cooking.

👉🏼 What to Avoid

You can also become familiar with the traits of dangerous mushrooms. Traits to avoid include:

- Old, decaying mushrooms

- Bite marks on the mushroom

- Insects in the mushroom

- Bright red, umbrella-shaped mushrooms, which might be poisonous Amanitas.

- Brain-looking caps in case they are false morels, which are toxic.

You may also like: 21+ Types Of Plants: From The Dinosaur Age To The Present (ID Guide, Pictures, And Facts)

Identifying Mushrooms By Their Key Traits

A dichotomous key to major groups of mushrooms is perfect for new enthusiasts. It shows the value of these keys and applies the identifying traits in this article.

Mycotrophs

It starts by asking if the mushroom is growing on another mushroom. Many mycotrophs are Cordyceps and Hypomyces genera, but not exclusively. Often, the parasitized mushroom is shriveled and blackened, so you’ll have to look closely.

Polypores

If the mushroom has gills and grows like a shelf on wood, it’s a polypore. You’ll see these everywhere while hiking in a forest. They live on and decompose dying and dead trees. They look corky and tough or fleshy and leathery.

Because of their shape from growing against a trunk, the gills don’t radiate from a central point. Instead, they take an irregular or concentric path. Cap colors often also vary in a concentric pattern. Genera include Ganoderma and Laetiporus.

Some polypores don’t grow against the trunk but feed on woody roots below the surface. These polypores will have pores instead of gills. You’ll need a hand lens to see the pores. They can also have no stem or a tough one.

Chanterelles and Trumpets

Chanterelles and trumpets are go-to examples of decurrent ridges and a vase shape. If they look like they have gills, they are actually false gills. They thrive as mycorrhizal species.

The main challenge with their identification is color. Sometimes it matters if the species is orange or pink. But depending on the light, you may not get a clear distinction. Genera include Cantharellus and Craterellus.

Gilled Mushrooms

Typically this includes agarics. But a few gilled mushrooms come from other fungi families, like Russula and Lactarius. And a few that are agarics or boletes like puffballs and bird’s nest fungi, but these lack gills.

Most identification features are only relevant to this group. So you have plentiful knowledge on how to narrow your possibilities.

Boletes

Boletes are common mushrooms with a classic toadstool shape. But they have pores instead of gills. They have fleshy, centrally-positioned stems and round cap outlines. They also leave non-white spore prints.

Almost all have mycorrhizal relationships with trees. So you’ll find them near a tree of some kind and have a guide for identifying it. Boletes also bruise blue.

Toothed Mushrooms

Beyond gilled and pored mushrooms, we can get into the stranger fungi. Toothed mushrooms can have a bearded look, a cup, a toadstool, have bloody textures mixed in, or be jelly. But they all have teeth or spines. Genera include Hydnum and Hericium.

Stinkhorns

No gills, pores, or teeth? Perhaps it is slimy and smells foul. Maybe one day, you saw a brown egg-like shape, and the next day, it took a bizarre shape. It was like a dead finger, fleshy Wiffle ball, or some other bizarre shape coming out of the ground. These are the stinkhorns.

They developed in warm and humid regions but have adapted to drier and more northern areas. They use their stink and slime to attract insects. The insects land, get covered in slime, which is also spores, or eat it and transport it.

Bird’s Nest Mushrooms

They are tiny. But if you find packed hay or mulch used for stormwater control, you have a good chance of finding these. Bird’s nest mushrooms are cup-like, brown, but may have light-colored “eggs” in them.

The nest, or peridium, catches rain, and the rain ejects the “eggs .”The “eggs” then latch on other surfaces like plant debris. They mostly live in warmer regions like the American Gulf Coast. Genera include Nidula and Mycocalia.

Cup Mushrooms

The rest of the cup-like mushrooms need more work to identify. They are also one of the most diverse fungal phyla, Ascomycota. This group is almost all microscopic. The cup mushrooms are one of the only ones visible to the naked eye.

The cups are still tiny. You’ll mostly identify them by their color, stem, and margin with a hand lens. They may turn blue with KOH and Melzer Reagent (iodine) tests. Often the ones you see are immature and show different traits than a guide.

Puffballs

Puffballs are soft, round mushrooms that, when mature, burst. You can apply pressure, such as with a stick, and trigger the event. Sometimes large ones burst, and the surrounding area will have colorful powder everywhere. They erupt on their own or in the rain.

They don’t always have a rounded shape. Some have lobes but contain an area full of powder all the same. Others are odd, like the earthstars, which look like brown, fleshy daisies with no stem. The powder is flesh in immature mushrooms.

Morels

Morels are popular with mushroom hunters who want a delicacy. Morels are hollow and have caps with pits, ridges, or wrinkles, like a brain. Some have less exaggerated traits and look smooth to their extra pitted counterparts. Genera include Morchella and Verpa.

False Morels

False morels look a lot like true morels. If the external appearance fooled you, cut into the stem to find it’s not thoroughly hollow. All false morels belong to the genus, Gyromitra.

Saddles

Saddle mushrooms have lobed caps that sometimes look like horse saddles. Other times they look like crumpled fabric or irregular cups. They also look so contorted it defies description as in the Helvella crispa. Genera include Gyromitra and Helvella, and most are mycorrhizal.

Jelly Mushrooms

They aren’t related to each other, but you can’t misidentify if a mushroom is a jelly type. They’re shiny globs that may remind you of jelly in the grocery store, though the mushrooms aren’t sweet. They decompose plants and other fungi.

Club and Coral Mushrooms

Club mushrooms look like sticks, and coral mushrooms resemble sea coral. They may grow on wood or grow from the ground. Like the jelly mushrooms, this group shares physical traits to identify them. But they aren’t related.

Crust Mushrooms

Some mushrooms grow low and flat to their substrate or as perpendicular fans. They attach to logs. These are the crust mushrooms, and their undersides have wrinkles instead of any gills or pores. A well-known crust mushroom is Trametes or Coriolus versicolor, the turkey tail.

The Rest

Many mushrooms don’t fit in a general shape category. Some are like Podaxis species that grow in the desert. They may grow underground as shaggy popsicle-shaped mushrooms. Spathulariopsis look like tiny ping pong paddles.

Syzygites is a fuzzy mushroom that coats over gilled mushrooms and deforms them. Apiosporina, also known as black rot, looks like black rope on tree branches.

You can find cedar apple rust or Gymnosporangium. It’ll be a dark orange ball on a cedar tree on a dry day but as a tentacle jelly on a rainy day. And Akanthomyces grows as spikes over dead moths.

You may also like: Are Strawberries Berries? The Answer Is Un-Berry-Vable!

Reliable Sources for Mushroom Identifier

- North American Mushroom Dichotomous Key for Genera

- Mushroom Dichotomous Key to Major Groups

- Missouri Guide of Edible and Toxic Mushrooms. These are also edible and toxic mushrooms typical of the northern hemisphere.

- Collection of Mushroom Identification YouTube channels, online tools, university, and Midwest resources

You may also like: 21 Edible Plants On The Appalachian Trail: Guide To Foraging On The AT

Mushroom Fun Facts

You may also like: 25+ Wonderful & Exotic Tropical Rainforest Plants: With Photos And Facts

FAQs

Can you survive eating a death cap?

You have a 50 percent chance of surviving eating a death cap without medical attention. And you have a 13 percent chance of survival if you do receive care. Also, it depends on how much you eat and how soon you get to a doctor.

Besides eating the mushroom, you also need to avoid ingesting or breathing in the spores.

What happens if you touch a white mushroom?

Some white mushrooms, like the common field mushroom, are safe to touch for most people. Others might have an allergic reaction. The deadliest mushroom to eat, the death cap, is also white yet safe to touch for most people.

False parasol, another white mushroom, can give mild gastric complications if you handle many with your bare hands.

Are backyard mushrooms poisonous?

Common safe mushrooms and common poisonous mushrooms grow in the same ecosystems. So it’s always possible a mushroom in your backyard is poisonous.

What does it mean if mushrooms are growing in your yard?

If anything, mushrooms show that you have a healthy yard. Mushrooms are an integral part of nature and occur everywhere. Even if you have never seen them, they’re likely there. They bind to almost all plants to exchange nutrients and decompose wood.

Are mushrooms poisonous to pets?

Dogs and cats are susceptible to the same mushroom toxins that humans are. Some of the symptoms are the same, like diarrhea, vomiting, shaking, and lethargy.