Outforia Quicktake: Key Takeaways

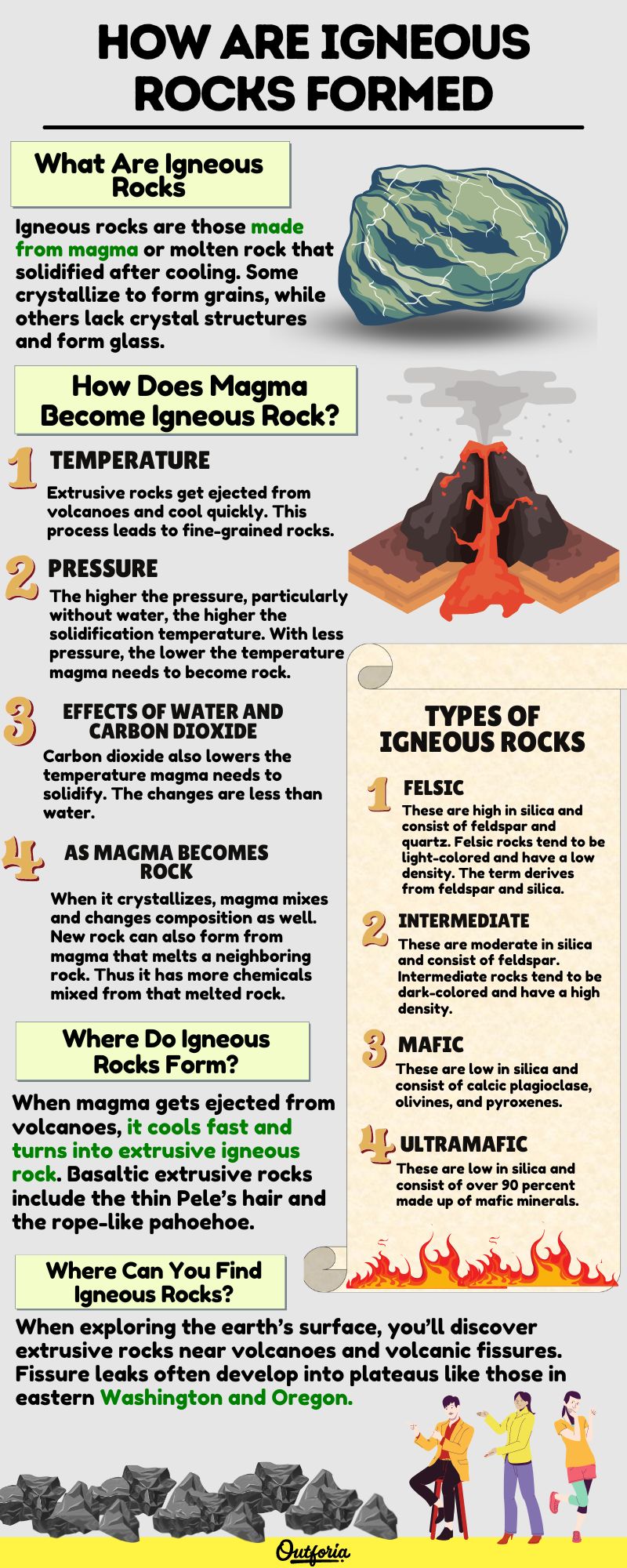

- Igneous rocks are formed from magma or molten rock that solidifies upon cooling, with temperatures between 1,100–2,400°F (600–1,300°C).

- They can be classified as extrusive (formed on the surface as lava) or intrusive (formed within the Earth’s crust).

- Igneous rocks’ appearance, texture, and composition depend on their origin and the rate at which their magma cooled.

- These rocks are typically classified by categories such as felsic, intermediate, mafic, and ultramafic, depending on their mineral and chemical content.

- Igneous rocks are essential for understanding Earth’s lower crust, upper mantle, and plate tectonics, and they can also be used in gardening for water retention and aeration.

In short, if you want to know what igneous rock is and how it formed, you can just imagine a volcanic eruption. But if you have more curiosity, you want to know the gritty details of how something viscous becomes rock.

If you already know some geology, you may be asking other questions. What happens on the surface as the lava and ash settle into their new states? Do rocks form in magma chambers below? How does plate tectonics influence formation?

Here is a detailed guide on what igneous rock are and how they form. It also addresses what distinguishes them from each other.

SHARE THIS IMAGE ON YOUR SITE

<a href="https://outforia.com/how-are-igneous-rocks-formed/"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/how-are-igneous-rocks-formed-infographics-11032022.jpg"></a><br>How are igneous rocks formed <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>You May Also Like: 30 Types Of Rock That You Shouldn’t Take For Granite: Pictures And Facts

What Are Igneous Rocks?

Igneous rocks are those made from magma or molten rock that solidified after cooling. Solidification happens between 1,100–2,400°F (600–1,300°C). Some crystallize to form grains, while others lack crystal structures and form glass.

They are one of the three major types of rocks. Igneous makes up most of the planet’s rocks. Others are sedimentary, made by compacting sediment or weathering other types. Then there are metamorphic rocks, which transition between igneous and sedimentary.

Igneous rocks can be extrusive or intrusive. When magma leaves the earth for the surface, it becomes known as lava. Lava hardens to form extrusive igneous rocks. Magma that crystallizes within the earth becomes intrusive igneous rocks.

The word “igneous” comes from the Latin “ignis,” which means “fire.” Many words revolving around such rocks have similar meanings. “Volcanic” comes from Vulcan, the Roman god of fire.

Not fiery in nature, but it is still a Roman reflection of geological origin. Intrusive igneous rocks also go by plutonic rocks. “Plutonic” comes from the Roman god of the underworld.

What Do Igneous Rocks Look Like?

Igneous rocks vary in appearance, texture, and composition. It depends on how their origin magma cooled. Also, some igneous rocks appear the same but come from magma that cooled at different rates.

How Do Igneous Rocks Form?

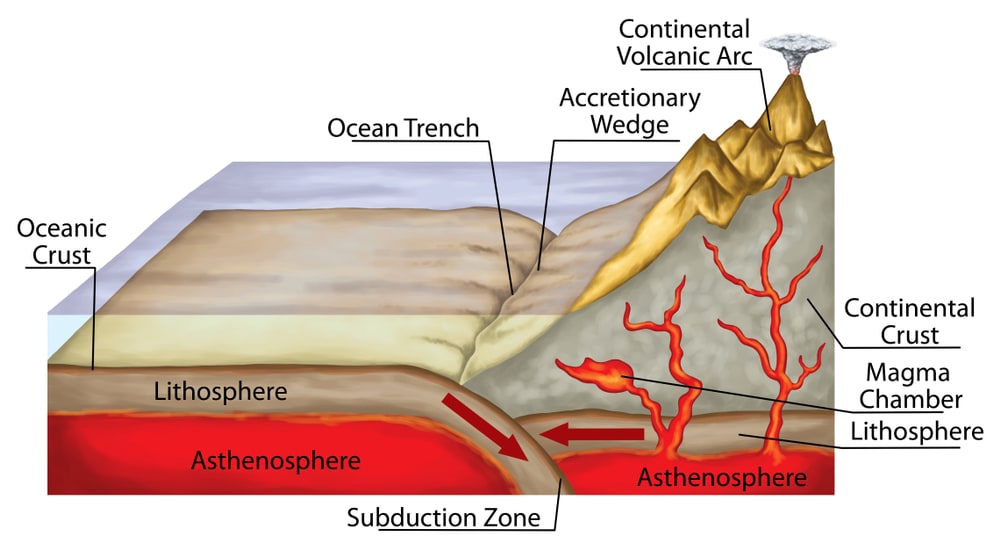

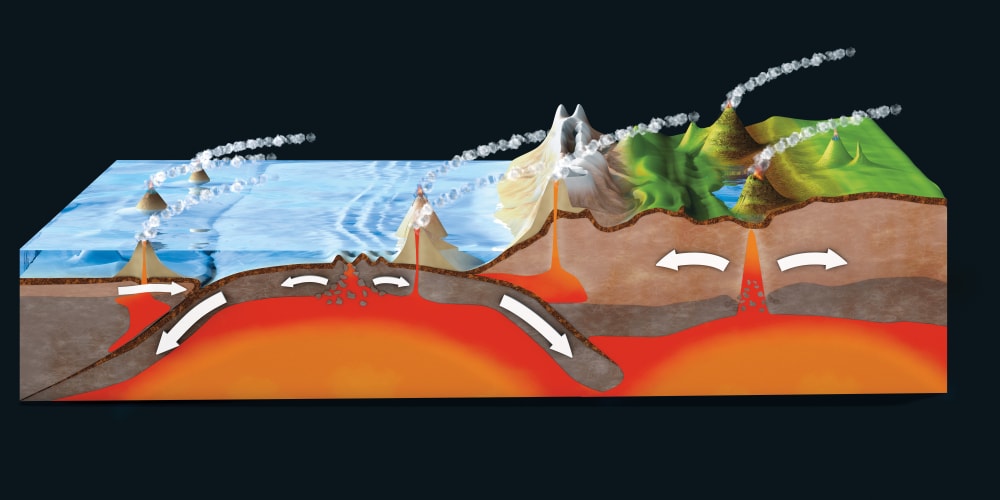

Igneous rocks are a byproduct of plate tectonics. Molten-hot chambers in the earth’s crust and mantle succumb to pressure. Shifting plates to push out some of the molten contents.

How Does Magma Become Igneous Rock?

Igneous rock requires cooling temperatures and pressure increases to form from magma. It can also come from an altered composition that’s more sensitive to temperature and pressure. Having a higher water concentration will have such an effect.

Sometimes intrusive rock becomes hot and relieved of pressure enough to return to a molten state. More heat can surge from the mantle during tectonic shifting. Pressure can change during that time as well.

Temperature

Extrusive rocks get ejected from volcanoes and cool quickly. This process leads to fine-grained rocks.

Intrusive rocks get pushed out of the magma chamber into other spaces in the earth’s crust. There, they cool slowly into coarse-grained rocks.

Pressure

The temperature that’s cool enough for an igneous rock to form changes depending on pressure.

The higher the pressure, particularly without water, the higher the solidification temperature. With less pressure, the lower the temperature magma needs to become rock.

The difference matters when it comes to the same rock forming in a shallower mantle location versus a deeper mantle location. The shallower has lower pressure and temperature, while the deeper has higher pressure and temperature.

But since the earth isn’t even throughout, igneous rocks and magma can end up at different depths. Solids can occur deeper toward the mantle, and magma can appear near the surface.

Chemistry: Effects of water and carbon dioxide

Water alters rock formation more than other molecules. It’s everywhere as well, even deep in the earth. It lowers the temperature magma needs to become a rock. Water can enter the mantle from subduction zones in the ocean.

Subduction zones are where an oceanic plate meets another. One dives into the mantle while the other bunches upward. Sometimes they form volcanic islands.

Carbon dioxide also lowers the temperature magma needs to solidify. The changes are less than water. But compared to itself, carbon dioxide has more impact at a higher pressure. The molecule is also less available than water in the mantle.

As Magma Becomes Rock

When it crystallizes, magma mixes and changes composition as well. For example, if you shake a scoop of lake soil with water and wait for it to settle, varying grain sizes settle at different rates. Minerals in magma will also settle at different rates. This creates grains in the resulting rock.

Because the rock has a new composition, so does the magma from where it separated. That remaining magma may produce a different kind of igneous rock.

Back to the lake example, the scoop settled with soil and gravel at the bottom and water on top. The bottom layers are like new rocks and get removed. Now the sample has water and soil. The following extraction can’t have gravel in its composition.

New rock can also form from magma that melts a neighboring rock. Thus it has more chemicals mixed from that melted rock. Also, magma with one composition can mix with magma of another before becoming rock.

You May Also Like: All About The 4 Types Of Volcanoes+ Formation, Eruption, And Facts

Where Do Igneous Rocks Form?

When magma gets ejected from volcanoes, it cools fast and turns into extrusive igneous rock. Basaltic extrusive rocks include the thin Pele’s hair and the rope-like pahoehoe.

Intrusive igneous rocks, or plutonic rocks, cool slowly while remaining inside the earth. They cool when they leave the magma chamber and create a pocket or intrusion in existing or country rock.

Below the surface, igneous rocks form the basis for tectonic plate crusts. Basalt and gabbro make up most of the oceanic plates, and sedimentary rock adds on top of granite continental plates.

Most magma types that form igneous rocks occur near each other in subduction zones. Some types develop in younger, shallower areas, while others in mature, deeper zones.

Where Can You Find Igneous Rocks?

When exploring the earth’s surface, you’ll discover extrusive rocks near volcanoes and volcanic fissures. Fissure leaks often develop into plateaus like those in eastern Washington and Oregon.

Intrusive igneous rocks will appear on the surface after uplift and erosion. These landscapes are large, continuous rocks like mountain ranges and shields. Yosemite National Park and the Canadian Shield are well-known.

Granite is a common and well-known intrusive igneous rock. Mountain ranges often have a skeleton or batholith built by intrusive rocks. With enough time, erosion may remove sediments and sedimentary rocks until batholiths surface.

Types of Igneous Rocks

Besides extrusive or intrusive, scientists classify igneous rocks by texture, minerals, and chemistry. Basalt is the most common extrusive rock and forms from lava flows. Granite is the most common intrusive rock.

Types of igneous rocks fall into four categories:

- Felsic: These are high in silica and consist of feldspar and quartz. Felsic rocks tend to be light-colored and have a low density. The term derives from feldspar and silica.

Examples: Granite, rhyolite

- Intermediate: These are moderate in silica and consist of feldspar. Intermediate rocks tend to be dark-colored and have a high density.

Examples: Diorite, andesite

- Mafic: These are low in silica and consist of calcic plagioclase, olivines, and pyroxenes. Mafic rocks tend to be dark colored thanks to iron and magnesium and have a high density. The name derives from magnesium and ferrous iron or ferric.

Examples: Basalt, gabbro

- Ultramafic: These are low in silica and consist of over 90 percent made up of mafic minerals.

Examples: Komatite, dunite

Some rocks will fall under one category based on their mineral content. But they can be under another category based on their chemical composition.

Pyroxene is an ultramafic mineral that can form a rock by itself. But if it forms rocks with enough silica, that rock will be chemically mafic.

Mineral Types of Igneous Rocks

Intrusive rocks benefit most from mineral identification. Common minerals found in igneous rocks include:

- Amphiboles

- Feldspars

- Micas

- Olivines

- Pyroxenes

- Quartz

Scientists categorize igneous rocks as feldspar and quartz content. Silica (SiO2) makes up most of quartz, so these rocks are silica-oversaturated. Feldspar types are silica-undersaturated.

If neither mineral is present, then the rock gets identified by iron, magnesium, and carbonate content. For instance, olivine has 90 percent iron- and magnesium-based minerals.

Some minerals called accessory minerals have nothing to do with the name of igneous rock but are present in small amounts. These include garnets, magnetite, and zircon.

Weathered igneous rocks may change enough to be alteration products. These changes come from new minerals from groundwater or surface exposure. Chlorites, iron oxides, talc, and others displace the original minerals. Glass can also become clay.

Chemical Types of Igneous Rocks

When you can’t identify an igneous rock by its mineral, you categorize them by chemistry. On a chemical level, most igneous rocks have an alkali versus silica scale. Alkali refers to the elements in the first column of the periodic table.

Silica (SiO2) is the most common molecule, followed by alkali metal oxides (Na2O, K2O).

Magma only cools and crystallizes from these elements:

- Aluminum

- Calcium

- Iron

- Magnesium

- Oxygen

- Potassium

- Silicon

- Sodium

Ninety percent of igneous rocks form silicate minerals built from these elements. Any silicate that doesn’t bond with other minerals will form quartz.

Low silicate amounts bond with magnesium oxide (MgO) and iron oxides (FeO, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4). Or sodium oxide or soda (Na2O) and potassium oxide or potash (K2O) displace silicate.

High silicate amounts have the opposite reaction. They get enriched by sodium oxide and potassium oxide but depleted by calcium oxide (CaO) and alumina (Al2O3)

Texture Variation of Igneous Rocks

The texture of igneous rock types matters less than mineral and chemical content. This is especially the case in the visible grains of intrusive rocks. But it’s still a way to narrow down what you’re looking at.

Because of how fast extrusive igneous rocks cool, the crystals can be minuscule. Geologists also call them aphanitic, meaning invisible in Greek.

Grains can also be non-existent, which is volcanic glass. Glass is a highly viscous liquid and thus hasn’t solidified to form grains. Even a rock as airy and sponge-looking as pumice falls into this category.

The small size of the grains makes identifying different rocks challenging. Geologists often need a thin section placed under a microscope to name an extrusive igneous rock.

Intrusive igneous rocks cool slowly and form crystals with large grains. This size is also known as phaneritic, meaning visible in Greek, grains that you can observe without a microscope.

Igneous Rock Structural Features

Igneous rocks form many structural features, including some surprising ones. Small-grained rocks, like pumice and other extrusive varieties, make up lightweight, sponge-looking rocks.

- Clastic structures: When a volcano explodes, it unleashes and deposits many rocks. As they cool, some add together, forming clastic structures. Non-volcanic rocks displaced in the explosion can also get caught up in the resulting shape.

- Flow structures: Lava or magma that remains in motion until it solidifies becomes flow structures. Since various flow levels will have cooled at different times, these rocks tend to have layers.

- Fractured structures: Igneous rocks subjected to repeated heating and cooling may develop fractures. Giant’s Causeway in Ireland is a famous example.

- Inclusion structures: When intrusive igneous rocks form, they start off as inclusion structures. They are masses of one rock composition surrounded by a completely different rock or texture.

- Pillow structures: Pillow structures are pillow-sized pockets of rock lined by a thin and glassy crust. The compartments cool extra fast from contact with water and are distinct from surrounding igneous rocks.

- Zonal structures: Igneous rocks that form in concentric patterns are called zonal structures.

You May Also Like: 23 Types Of Mountains: Your Definitive Guide

Fun Facts

- Our understanding of the lower crust, upper mantle, and plate tectonics comes from igneous rocks and their parent magma.

- Gardeners often add igneous rocks for water retention and aeration. Common products include perlite and vermiculite.

FAQ

How much igneous rock is in the earth’s crust?

Igneous and metamorphic rocks make up most of the earth’s continental crust. Continental plates average 20 mi (30 km) thick.

Igneous rocks alone make up most of the oceanic crust. Oceanic plates average 5 mi (8 km).

What is the difference between a rock and a mineral?

Rocks consist of minerals cemented together like sedimentary rocks or molded like igneous rocks. Metamorphic rock is an intermediate state. Minerals are elements or compounds with a consistent structure, like a lattice or crystal.