Have you ever been told to get your head out of the clouds?

Then this article is for you.

Whether you’re an aspiring meteorologist or you’re an avid storm chaser, it’s hard to argue the majestic allure of the clouds overhead.

But, even if you like to spend your hours watching the clouds go by, how much do you actually know about the different types of clouds?

From towering cumulonimbus to wispy cirrus, we’re here to introduce you to the wonderful world of clouds. In this article, we’ll discuss the 10 most common and 14 most extraordinary types of clouds. We’ll also offer some insight into how clouds form so you can impress your friends with your cloud spotting knowledge.

10 Main Types of Clouds

If you’re brand-new to the world of cloud spotting, we highly recommend reading through our section on how clouds are classified and how they form below before you check out this list of the different types of clouds.

We put our list of the various cloud types first in this article because we know that you’re probably eager to learn more about these amazing clouds (we know we would be!).

But, we do highly recommend orienting yourself with some cloud classification basics before you dive into the various cloud types. Doing so will help you better understand and remember the different cloud types.

However, without further ado, here are the 10 basic types of clouds. Let’s get started!

1. Low-Level Clouds

Since there are so many different types of clouds, we’ve organized them here based on how high up you’re likely to find them in the atmosphere. First up on our list are our low-level clouds, which are mostly found between the surface of the Earth and 7,000 feet (2,000 m) above the ground. These clouds include:

1.1 Cumulus (Cu)

The puffy, mound-shaped clouds that you see on sunny days, cumulus clouds are normally white or light grey. There are many different species of cumulus clouds, but they are mostly comprised of supercooled water droplets rather than ice crystals due to the fact that they exist at low levels of the atmosphere.

The name “cumulus” actually comes from the Latin word of the same spelling that roughly translates to “heaps.” Indeed, these clouds usually look like lumps of cotton floating in the sky.

That being said, due to the many different subtypes of cumulus clouds, it’s hard to use them to predict the weather. While some cumulus clouds, like cumulus humilis, are fair-weather clouds, others, such as the cumulus congestus, can be the precursors to thunderstorms or even tornadoes.

Regardless of whether you use them to predict the weather, cumulus clouds are very fun to look at. They often form into funky shapes, which make them excellent for cloud spotting during a free afternoon at your campsite.

1.2 Stratus (St)

Named after the Latin prefix “strato-,” meaning “layer,” stratus clouds are large, horizontal clouds. These clouds tend to be light to dark grey in color and they’re often to blame when the sky is looking grey and dreary.

Stratus clouds usually have minimal features, so there’s not much to describe about them besides their uniform, flat shape. However, there are some subtypes of stratus clouds, such as the stratus fractus, that form in irregular, broken shapes.

As a general rule, stratus clouds form as a large parcel of air is lifted upward as a single unit. This upward motion throughout a wide geographic region gives the clouds a uniform shape, which is why stratus clouds often lack features.

As far as weather forecasting goes, stratus clouds can sometimes result from a thermal inversion. They are often also associated with some anticyclones. Furthermore, you can sometimes find stratus clouds that are associated with warm fronts that are moving overhead, indicating that a light drizzle is likely to occur.

1.3 Stratocumulus (Sc)

A sort of intermediary between stratus and cumulus clouds, stratocumulus clouds are a funky type of low-level cloud. These clouds are puffy and lumpy, like cumulus clouds, but they often form into groups, waves, or lines, which give them a flatter, layered appearance, like what you’d see with a stratus cloud.

Stratocumulus clouds are common over the ocean, but they rarely produce precipitation other than very light rain or snow. Sometimes, stratocumulus clouds occur at the very start or very end of severe weather, but this isn’t a very reliable rule for weather forecasting.

However, one cool feature that you often see with stratocumulus clouds is crepuscular rays. Also known as sunbeams, crepuscular rays form when the light from the sun is scattered off of particulates or water vapor in the sky. This effect is particularly common with broken layers of stratocumulus clouds, particularly near sunrise or sunset.

We should mention that stratocumulus clouds are often mistaken for altocumulus clouds because they share a similar shape. However, stratocumulus clouds are low-level phenomena so they appear to be much bigger in the sky.

If you’re having difficulty distinguishing between stratocumulus and altocumulus clouds, point your hand in the direction of one of the clouds. If the cloud is roughly the size of your fist, it is likely stratocumulus. Otherwise, if the cloud is about the size of your thumb, it’s probably altocumulus.

1.4 Nimbostratus (Ns)

A combination of the Latin words “nimbo-,” meaning precipitation, and “strato-,” meaning layer, nimbostratus are a type of cloud that’s highly associated with active precipitation. These clouds are typically classified as low-level clouds, but they actually form mostly in the mid-level of the troposphere. So, you may see it classified differently depending on your source.

Nimbostratus clouds are usually thick, widespread layers with a greyish color. If you look outside and it looks drizzly, dreary, and all-around blech, a nimbostratus cloud is likely to blame.

Most nimbostratus clouds will form along a frontal boundary, especially among occluded or warm fronts. This is because the steadily rising mass of warm air associated with these fronts provides the lift necessary to create these widespread clouds.

However, nimbostratus clouds are not associated with thunderstorms. Rather, they do not produce lightning on their own and they are generally responsible only for rain, snow, and other types of precipitation.

- Learn to identify every cloud type and understand its implications for the weather

- The Cloud Book follows a logical progression, making it easy to understand

- Features a detailed introduction on the history of cloud classification

- Packed with stunning images from the Met Office's archive

- Written by post-doctoral cloud research fellow Dr Richard Hamblyn, whose previous book "The Invention of Clouds" was shortlisted for the 2002 Samuel Johnson Prize

- The definitive guide to the clouds and the skies.

2. Mid-Level Clouds

At this point, we’ve discussed all of the cloud types that normally form in the lowest layers of the atmosphere. So, we’re ready to move upward in altitude to the mid-level clouds, which form between about 7,000 feet and 23,000 feet (2,000 m to 7,000 m) above the ground. Here’s what you need to know.

2.1 Altocumulus (Ac)

Altocumulus clouds are similar to the cumulus clouds you see in the lower levels of the troposphere, but they are located at a slightly higher altitude. They tend to look like large patches of puffy clouds that can cover wide areas of the sky.

These clouds can form in a number of different ways, including through the lifting of moist pockets of air. Sometimes, they can also form through the breakup of altostratus clouds.

As a general rule, altocumulus clouds are associated with calm weather. They do not usually produce precipitation on their own, but they can form virga (more on this in a bit). So, these clouds are nice to look at and they usually don’t indicate any incoming severe weather.

2.2 Altostratus (As)

Like altocumulus clouds, altostratus clouds also form at the mid-level of the troposphere. As the suffix “-stratus” suggests, these clouds also form layers, like what you see with low-level stratus clouds.

Altocumulus clouds are generally quite thin and they’re usually composed of both water droplets and ice. For the most part, these clouds form as cirrostratus from higher in the troposphere descends down to a lower altitude.

You will sometimes see altostratus ahead of an incoming weather system. These clouds often form in front of either a warm or occluded front, which could indicate that rain is on the horizon.

One cool thing to remember with altostratus, though, is that these clouds often produce optical effects. Some of the more common optical effects that you might see with altostratus include cloud iridescence and coronas, so keep your eyes peeled if these clouds are in the sky.

3. High-Level Clouds

Once we move into the highest level of the troposphere, there are three main types of clouds that you ought to look out for. Due to their high altitude, these cloud types are almost always composed of ice crystals. They also tend to look very small to the human eye as they are located so far above the Earth’s surface.

Here’s what you need to know:

3.1 Cirrus (Ci)

Known for their characteristic wispy formations, cirrus are gorgeous clouds that form at the highest altitudes in the troposphere.

These clouds are relatively simple to identify because they look like strands of thin, white hair. They may also turn bright pink or orange at sunrise and sunset.

Cirrus normally form as a result of the lifting of a dry air parcel. Since this air is very dry and since the air is very cold in the upper troposphere, the little moisture that remains in the air parcel transitions straight from water vapor to ice crystals in a process called deposition.

Most cirrus form ahead of a warm front, so they often indicate that changing weather is en route to your location. But, you won’t ever experience precipitation falling from cirrus clouds as any rain or snow that falls evaporates long before it hits the ground.

3.2 Cirrocumulus (Cc)

Creating beautiful little specks of white tufts in the upper troposphere, cirrocumulus clouds are a high-level cloud formation that’s normally a sign of fair weather.

Technically speaking, cirrocumulus clouds contain dozens or hundreds of miniature cloud puffs that are known as cloudlets. These cloudlets are mostly made up of ice crystals and they often look like a fish’s scaly skin when grouped together. So, you may hear some people refer to these clouds as a mackerel sky.

As we’ve mentioned, cirrocumulus clouds are usually associated with calm weather. They form in a number of ways, most notably when turbulent eddies within the upper atmosphere break up a layer of cirrus clouds.

3.3 Cirrostratus (Cs)

Cirrostratus clouds are very thin, layered clouds that are found in the upper part of the troposphere.

These clouds often look like a translucent veil that covers much of the sky. In fact, they can cover thousands of miles of the sky in any direction, creating a slight amount of overcast on an otherwise sunny day.

Cirrostratus form as a large parcel of air rises very slowly and uniformly into the upper atmosphere. These clouds can sometimes indicate that a warm front is on the horizon, so it may be best to watch out for some precipitation in the coming days if you see these clouds in the sky.

4. Clouds With Vertical Development

Although most clouds are found within a distinct layer of the troposphere, there’s one cloud type that doesn’t quite follow the rules. Indeed, the cumulonimbus cloud is one of the few cloud types that has substantial vertical development.

This means that the cumulonimbus can grow so tall that it exists throughout a substantial portion of the troposphere. Here’s a closer look at this fascinating type of cloud:

4.1 Cumulonimbus (Cb)

Sometimes considered to be the “king of clouds,” the cumulonimbus is a truly spectacular atmospheric phenomenon.

These clouds form throughout periods of sustained convection in the atmosphere. When the atmosphere is primed with warm, moist air, strong updrafts can cause cumulonimbus clouds to develop from a small cumulus into a towering monster of a cloud.

Cumulonimbus clouds can be tens of thousands of feet tall as they can have cloud bases as low as about 1,100 feet (335 m). Sometimes, these cumulonimbus clouds will grow to be so tall that their strong updrafts actually punch through into the stratosphere creating something called an overshooting top.

One of the characteristic features of a mature cumulonimbus cloud is an anvil top. Aptly named, anvil tops are long, flat anvil-like protuberances that extend out from the upper portion of the cloud along the tropopause, which is the transition zone between the troposphere and the stratosphere.

The problem with cumulonimbus clouds is that they can bring severe weather. Damaging straight-line winds, large hail, lightning, and tornadoes are all possible with these clouds. So, if you see one on the horizon find some shelter to protect you as you ride out the storm.

Other Special Clouds

There are still other varieties of clouds that our eyes can’t meet. Here are the 14 other special clouds that you ought to know!

1. Upper Atmosphere Clouds

While the vast majority of clouds in the Earth’s atmosphere form in the troposphere (the lowest layer of the atmosphere), some clouds can form at higher altitudes. In particular, there are two known kinds of clouds that form in the Earth’s upper atmosphere. These include:

1.1 Noctilucent Clouds (NLC)

Found only in the mesosphere at an elevation of 31 to 53 miles (50 to 85 km) above the Earth’s surface, noctilucent clouds are the world’s highest clouds. Also called polar mesospheric clouds, these clouds are comprised solely of tiny water crystals.

It’s believed that these clouds form as a result of a mixture of dust, water vapor, and extremely cold temperatures that all happen to make it into the mesosphere.

However, researchers aren’t sure yet how the dust and the water vapor end up in the upper atmosphere as these particles are mostly found in the troposphere. One theory is that the dust comes from volcanic eruptions or potentially from meteors, but more research is needed to confirm this suspicion.

Furthermore, since the mesosphere is exceptionally dry, ice crystals can only form in this layer of the atmosphere at temperatures that are below -184ºF (-120ºC).

So, the chances that there will be enough dust and water vapor in the mesosphere at the same time, alongside exceptionally cold temperatures, is very rare. This means that any sighting of a noctilucent cloud is a special moment that’s certain to be a highlight of any cloud spotter’s career.

Do keep in mind, though, that noctilucent clouds are usually either colorless or very pale blue, which can make identification tricky. You will generally only see them between 50º and 65º north and south in latitude during the summer months, which also makes them particularly difficult to spot.

1.2 Polar Stratospheric Clouds (PSC)

Our second form of upper-atmosphere cloud, the polar stratospheric cloud is a stunning cloud formation that’s generally only seen in the polar regions.

Commonly called nacreous clouds or mother of pearl clouds, these clouds form in the stratosphere from about 6 to 15 miles (10 to 25 km) above the Earth’s surface. These clouds get their common names from their beautiful rainbow colors, which look a lot like the shiny iridescence of mother of pearl.

As with noctilucent clouds, polar stratospheric clouds form when small amounts of moisture and dust make their way into the stratosphere on very cold nights in the polar regions. They are considered to be quite rare, though, and you are more likely to see them in the Antarctic than in the Arctic.

While these clouds are beautiful, however, researchers have recently discovered that they’re actually contributing to the depletion of the ozone layer. It turns out that the formation of these clouds helps encourage the destruction of ozone in the stratosphere by interacting with nitrogen and chlorine atoms in the atmosphere.

To make matters worse, scientists have also realized that polar stratospheric clouds are becoming more common each year, which suggests that the ozone hole might grow in the near future.

2. Special Clouds

Unlike all of the clouds that we’ve discussed so far, the clouds in this section don’t quite fit into any neat category. Many have unique shapes or odd formation patterns that make them difficult to categorize elsewhere.

Further, many of these clouds are actually defined by the World Meteorological Organization as “supplementary cloud features” rather than as clouds in their own right. However, you’ll often hear people referring to the phenomenon in this section as clouds in informal conversation, so they’re definitely worth knowing if you plan to do a lot of cloud spotting.

2.1 Mammatus Clouds

One of our personal favorite clouds, mammatus clouds are a stunning cloud formation that you’ll sometimes see ahead of a thunderstorm.

Technically speaking mammatus clouds are a supplementary feature of clouds rather than their own cloud type. But, we regularly refer to them as a type of cloud, so they’re worth discussing in more detail here.

These clouds tend to form into rounded pouches, sort of like a cow’s udders, on the underside of a cloud. They form as a result of sinking air, which makes them somewhat unique in the world of clouds. Indeed, while most clouds form as air rises, mammatus are one of the few that form as air sinks toward the ground.

You’ll generally find mammatus on the base of cumulonimbus clouds, but they’re usually only visible for about 10 to 15 minutes at a time. If you do see these clouds, though, be warned—severe weather is probably on its way. So, take cover if you see mammatus on the horizon as heavy rain, hail, strong winds, and even tornadoes may be heading toward your location.

2.2 Lenticular Clouds

One of the most recognizable types of clouds, lenticular clouds (lenticularis) are lentil or almond-shaped clouds that form in the lower to middle parts of the troposphere. These clouds often resemble flying saucers and they are technically a variant of either an altocumulus, stratocumulus, or cirrocumulus cloud.

Lenticular clouds form as wind blows over a large object, such as a mountain. If there’s sufficient moisture in the air as the wind blows over the mountain, this moisture can condense as it gets pushed up and over the mountain’s summit. When this happens, clouds can form above a mountain’s summit in this unique lens-like shape.

However, as we’ve mentioned, lenticular clouds can look suspiciously like a spaceship in low light. As a result, some people believe that reported UFO sightings may actually be misidentified lenticular clouds.

2.3 Arcus Clouds

Similar to roll clouds, arcus clouds are a type of accessory cloud that forms at the front of a cumulonimbus.

These clouds are known for their large, arch-shaped formation, which makes them look particularly foreboding ahead of an advancing thunderstorm. For the most part, they form along the leading edge of a gust front ahead of a thunderstorm, but you may also see them associated with other types of convection, such as a cold front or a sea breeze.

When these clouds are on the horizon, it’s likely time to start looking for shelter from the wind and the rain. While they’re not always associated with severe thunderstorms, you can generally expect at least some high winds to roll through your location as the arcus cloud moves overhead.

2.4 Roll Clouds

A type of arcus cloud, roll clouds are generally associated with the gust front of a thunderstorm. Unlike arcus clouds, however, roll clouds have a very long, tube-like shape.

When arcus clouds move overhead, it can look like they’re literally rolling over the ground below. This can make them look quite dramatic, especially when the dark skies of a thunderstorm trail closely behind.

For the most part, roll clouds are quite rare. But, they are known to occur in specific parts of the world, such as northern Australia.

In fact, in the Gulf of Carpentaria in Northern Australia, roll clouds are somewhat common. In this part of the world, they’re often called Morning Glory clouds and they normally happen between September and November each year.

2.5 Cap Cloud / Plieus

A type of accessory cloud, cap clouds are a type of cloud that forms over another type of cloud. These clouds, which are often called pileus (Latin for “cap”) tend to form over cumulus or cumulonimbus clouds.

For the most part, cap clouds are short-lived. They tend to form as a result of a very strong updraft and lots of moisture in the atmosphere. So, if you see these clouds, severe weather might be on its way to your location.

In some instances, pileus clouds also appear to be rainbow in color. These rainbow colors are the result of an optical phenomenon called cloud iridescence, which is quite the sight to see.

2.6 Billow Clouds/Kelvin-Helmholtz Clouds

Arguably the coolest type of cloud on our list, billow clouds (also called Kelvin-Helmholz clouds) are a very rare atmospheric phenomenon. These clouds look surprisingly similar to ocean waves, which is why they’re so amazing to look at.

Billow clouds form as a result of large wind shear in part of the atmosphere. Wind shear refers to a change in either speed or direction in a parcel of air over a certain distance.

In particular, these clouds form as a result of Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, which is a much more complex physical concept than we can get into here. However, suffice it to say that if you see billow clouds in the sky, you can fairly accurately extrapolate that the atmosphere must be very windy and turbulent.

2.7 Contrails

Believe it or not, but the contrails that come out of the planes that fly overhead are a type of cloud. The word contrail is actually short for the phrase “condensation trail,’ which provides a bit of a hint as to how these awesome clouds form.

Contrails are found high up in the troposphere where commercial aircraft and jets tend to cruise. They form as the water vapor in the atmosphere condensates around the particulate matter coming out of the aircraft’s exhaust.

Looking at contrails can tell you a lot about the humidity in the upper troposphere. For example, contrails that disappear almost immediately after forming indicate that the humidity of the upper troposphere is quite low. Meanwhile, persistent contrails that stick around for a few minutes indicate that it’s quite humid in the upper troposphere.

This might not seem like a big deal, but very humid conditions in the upper troposphere could be an indicator that more cloud formation is in the cards for the near future.

2.8 Asperitas

A new type of cloud that was first added to the International Cloud Atlas in 2017, the asperitas is a stunning cloud with a wavy pattern.

While not much is known about these clouds, we do know that they have a wave-like pattern on their underside. This makes it feel like there’s an upside-down ocean with wavy seas above you in the sky.

Most aspiratas clouds are darky colored and opaque. They usually form either with stratocumulus or altocumulus clouds in the low- to mid-levels of the troposphere.

It’s not clear why these clouds form, but we do know that they’re somewhat common over the Great Plains in the United States. They’re also associated with thunderstorms, even if they’re not responsible for precipitation.

2.9 Pyrocumulus Cloud

Also known as a flammagenitus cloud, pyrocumulus clouds are a relatively rare type of cloud.

These clouds form as a result of convection that starts due to extreme heat. For example, pyrocumulus clouds can form as a result of a volcanic eruption or wildfire.

Although not much is known about these clouds, it’s thought that the heat from these forest fires and volcanic eruptions leads to convection in a localized area. This convection then causes the formation of large, billowing clouds that, in many ways, resemble immature cumulonimbus clouds.

Most pyrocumulus clouds are somewhat grey or brown in color due to the high amount of ash or smoke in the fire or volcanic eruption that caused the cloud to form in the first place.

Depending on the other atmospheric conditions at work at the time, some pyrocumulus clouds can either encourage a fire to grow larger or they can hinder the further spread of the flames. When fires get very large, they can create strong, sustained convective cells that can eventually produce cumulonimbus flammagenitus clouds.

These cumulonimbus flammagenitus clouds are not well understood by meteorologists, but there is a push to classify them as their own cloud type. Interestingly, the convective cells within cumulonimbus flammagenitus can even develop so much that they create thunderstorms such as those seen during the 1991 Pinatubo volcanic eruption in the Philippines.

2.10 Funnel Cloud

Also called a condensation cloud, a funnel cloud is a type of cone-shaped feature that forms out of the base of certain types of cumulus and cumulonimbus clouds. These funnel clouds form when a rotating column of air extends out of the base of a cloud, often due to very strong updrafts and downdrafts of air.

Now, if you’ve seen a photo of a funnel cloud, you may be asking yourself how they’re different from tornadoes. Indeed, funnel clouds and tornadoes do look a whole lot alike, and that’s because they’re (almost) the same thing.

According to the National Weather Service, a funnel cloud can be considered a tornado if it either touches the surface of the Earth or if it has a cloud of debris below it. So, all tornadoes are funnel clouds, but not all tornadoes are funnel clouds.

Needless to say, if you see a funnel cloud on the horizon, please take shelter. While it’s possible that the funnel cloud will not touch the ground and that it will not form a tornado, funnel clouds on their own are a sign of severe weather. Seek out a sheltered space in a basement or first-floor room that’s far from any windows until the storm passes.

3. Other Cloud Features

So far in this article, we’ve discussed the various types of clouds. Nevertheless, there are a few other features that form in the sky that you might see but that aren’t technically classified as clouds.

To ensure that you’re accurate in all your cloud spotting endeavors, here are some other cloud features that you ought to be aware of:

3.1 Fallstreak Hole

Sometimes called a “hole punch cloud,” fallstreak holes are large circular gaps that form in both altocumulus and cirrocumulus clouds. These gaps are instantly recognizable as they tend to stick out from the otherwise uniform cloud layers that surround them.

Fallstreak holes often form when a plane passes through an altocumulus or cirrocumulus cloud layer.

As the plane passes through these layers, it can bring with it ice crystals that have formed on its surface during flight. These ice crystals then bind to water droplets in the cloud layer that freeze, grow, and then precipitate out of the cloud layer before evaporating lower down in the troposphere. These falling ice crystals then leave behind a hole that we call a fallstreak.

Fallstreak holes don’t necessarily signify any impending bad weather. So, there’s not much to worry about if you see one on the horizon. But, they are quite rare, so if you’re lucky to see one, be sure to snap a photo before it disappears!

3.2 Virga

Virga are a feature that’s commonly seen on clouds in very dry environments, like the desert. Also called precipitation trails or fallstreaks, virga are essentially large wisps of water or ice that descend from a cloud in dry conditions.

These virga represent precipitation that’s falling from a cloud but that evaporates into the atmosphere before it ever hits the ground. As a result, you can see the water falling to the ground from the cloud, but the virga streak eventually terminates when all the moisture evaporates.

Most clouds with virga pass overhead with little fanfare, so they’re usually not anything to worry about. But, some clouds with virga can create microbursts, which are localized downdrafts of high-velocity air that can cause serious damage in a matter of minutes.

So, if you see virga coming out of a large cumulus cloud, keep an eye out for any rapidly changing weather conditions.

You may also like: Find Out What Causes Tides: Complete with Illustrations, Explanations, Descriptions, and More!

Cloud Classification

Now that you’re familiar with the different types of clouds, it’s time to talk about how clouds are classified. Indeed, you will find that it’s substantially easier to remember the different cloud types and to spot clouds in the great outdoors if you understand how they’re classified.

So, in this section, we’ll introduce you to two of the most commonly used cloud classification systems as outlined by the American Meteorological Society. That way, you can have a solid understanding of the various organizational methods that scientists use to classify clouds in order to help you in your cloud-watching endeavors.

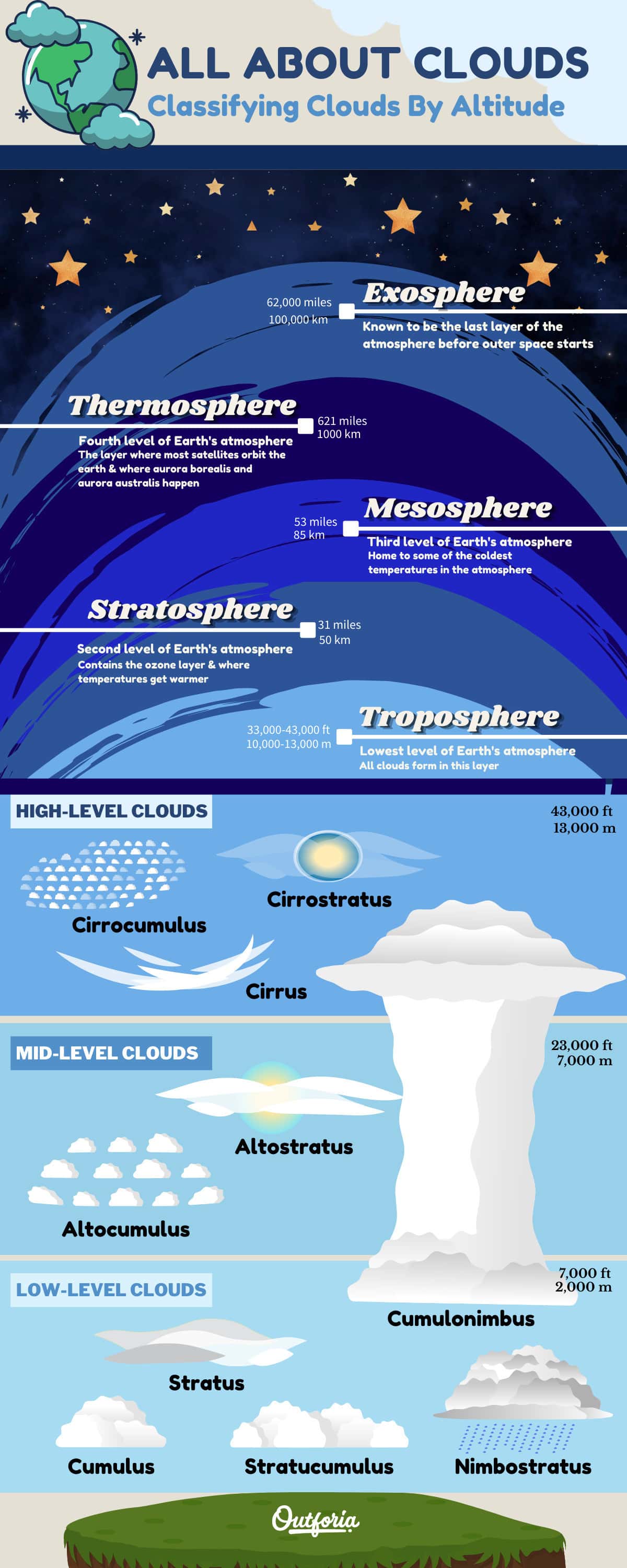

Classifying Clouds By Altitude

The first type of cloud classification system that you might see is one where clouds are organized based on their typical altitude in the sky.

When you look up at the sky, you may not realize that there’s a lot more to our atmosphere than meets the eye. There are actually multiple layers of the atmosphere, each of which has its own unique characteristics.

Share This Image On Your Site

<a href="https://outforia.com/types-of-clouds/"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Cloud-Classification-Infographics-0421.jpg"></a><br>Cloud Infographic by <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>In fact, there are five layers of the Earth’s atmosphere, which are as follows:

- Troposphere – Starting at the ground and extending up about 33,000 feet (10,000 m), the troposphere is the lowest level of the atmosphere. Nearly all of our clouds form in this layer because the troposphere contains 99% of the atmosphere’s water vapor. There are multiple sub-layers in the troposphere that we’ll discuss in a bit.

- Stratosphere – Stretching from the top of the troposphere to about 31 miles (50 km) above the ground, the stratosphere is the second atmospheric layer. This layer contains the ozone layer at around 12.5 miles (20 km) above the ground. This is also the location of the upper part of the jet stream and it is the cruising altitude for passenger jets. Oddly enough, temperatures actually get warmer with altitude in the stratosphere.

- Mesosphere – The mesosphere extends from the top of the stratosphere to about 53 miles (85 km) above the ground. Here, the temperatures get colder with altitude and this region is home to some of the coldest temperatures in the atmosphere. Air pressure in the mesosphere is just a fraction of what we experience on the ground.

- Thermosphere – The thermosphere exists from the top of the mesosphere to about 311 to 621 miles (500 to 1,000 km) above the ground. Like the stratosphere, temperatures in the thermosphere get hotter with altitude. In fact, they can reach up to 3,632ºF (2,000ºC). Many satellites orbit the planet in the thermosphere. This is also the layer of the atmosphere where you can see the aurora borealis (northern lights) and the aurora australis (southern lights).

- Exosphere – While some scientists argue that this is not a layer of the atmosphere, the exosphere is usually considered to be the very last remnant of the Earths’ atmosphere before outer space really starts. There’s no hard-and-fast upper boundary for this layer, but it’s believed to end around 62,000 miles (100,000 km) above the surface of the Earth.

Okay, you might be wondering why we just spent some time discussing all of the layers of the Earth’s atmosphere when clouds mostly happen in the troposphere.

The answer is that truly understanding clouds and being able to identify them properly starts with having a good conceptual model in your head of the Earth’s atmosphere. You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to learn this stuff, but a good working knowledge of the layout of the atmosphere is helpful.

Now, with all that in mind, let’s focus our attention on the lowest layer of the atmosphere: the troposphere.

The vast majority of the clouds that we see form within the troposphere. In fact, the majority of our weather happens due to changes in the Earth’s troposphere. Despite this, there are also various levels of the troposphere, each of which serves as the breeding ground for different types of clouds.

That being said, do keep in mind that these layers are not fixed in the sky. There is no clear-cut boundary between the layers of the troposphere and these layers will fluctuate based on prevailing atmospheric conditions.

But, this is what you can expect from the various cloud heights:

- Low-Level Clouds – These clouds form between the surface and 7,000 feet (2,000 m) above the ground.

- Mid-Level Clouds – Mid-level clouds can be found between about 7,000 feet and 23,000 feet (2,000 m to 7,000 m) above the ground.

- High-Level Clouds – The loftiest of the clouds, high-level clouds exist between about 16,000 feet and 43,000 feet (5,000 m to 13,000 m), but they are mostly above 23,000 feet (7,000 m).

- Clouds With Vertical Development – Finally, there are some clouds that don’t fit neatly into these tropospheric layers. These clouds are considered to have “vertical development.” which means that they extend throughout multiple layers of the troposphere, like towering thunderstorm clouds (more on those in a bit).

Classifying Clouds By Genera, Species & Variety

Developed by Luke Howard in 1803, this second system for classifying clouds by their genera, species, and variety is, in many ways, an advancement of the simplified method of categorizing clouds based on their altitude in the troposphere.

That being said, Howard’s cloud classification scheme provides a more robust set of guidelines for naming and identifying all cloud types. It has since been adopted by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) as part of their cloud atlas.

Similar to what we see in the taxonomy of animals and plants, this system uses a system of Latin names to identify clouds. With a few notable exceptions, clouds named using this system have a genus, species, and potentially a variety (sort of like a subspecies). Here’s how it works.

Cloud Genera

Just like with plants and animals, the vast majority of clouds are technically classified into genera. However, there are substantially fewer cloud genera than there are for the different types of lizards, for example, so it’s a bit easier to memorize this cloud naming system.

In Howard’s cloud classification system, there are 10 genera that are often called the “basic cloud types.” These include:

- Cumulus

- Cumulonimbus

- Stratus

- Stratocumulus

- Nimbostratus

- Altostratus

- Altocumulus

- Cirrostratus

- Cirroculumulus

- Cirrus

We discussed all of these cloud types in detail at the start of this article, so we won’t repeat ourselves here.

But, we should note that most cloud spotting enthusiasts will name clouds just by their genera, rather than trying to figure out a cloud’s species. Since determining a cloud’s species can be very difficult, getting comfortable with identifying these 10 genera is a superb starting point.

Cloud Species

In addition to the 10 genera that we’ve listed above, most clouds can also be further categorized within a certain species. These species and their defining characteristics include:

- Fibratus – Thin clouds with fine, hairlike whisps. These clouds are mostly found with the genera cirrus and cirrostratus.

- Uncinus – Similar to the thin wisps of fibratus but with curved hooks at the end. Found only with the genus cirrus. These clouds are sometimes called mares tails or fish hooks.

- Castellanus – Clouds that have tower-like protuberances that look similar to the turrets of a castle. Found primarily with the genera stratocumulus, cirrocumulus, altocumulus, and cirrus.

- Spissatus – Fine, wispy clouds that bunch together into dense collections, sort of like a feather. This cloud is only found in the genus cirrus.

- Floccus – Clouds that have small, puffy tufts and wispy tails. These clouds often have virga as a supplementary feature and they are found in the genera stratocumulus, altocumulus, cirrus, and cirrocumulus.

- Nebulosus – A highly uniform cloud with no distinct details, cloud tufts, whisps, or other features. Nebulosus clouds often look like a fine veil over the sun and they are found in the genera stratus and cirrostratus.

- Stratiform – Clouds with horizontal layers, derived from the Latin strato- (layer). Found as stratus, cirrostratus, stratocumlus, and altostratus.

- Lenticularis – Any type of wide, smooth cloud that takes on a round shape, much like the lens of a set of eyeglasses. Lenticularis or “lenticular” clouds are usually found in the genera altocumulus, cirrocumulus, and stratocumulus.

- Fractus – Featuring ragged, irregular shapes, fractus clouds are normally small and located under the base of other clouds. They are found mostly in the genera stratus and cumulus.

- Humilis – Commonly called fair-weather clouds, humilis clouds have flat bases and cotton candy-like tufts. They are only found in the genus cumulus.

- Mediocris – Large, puffy clouds with quite a bit of vertical development (height). These clouds are only found in the genus cumulus.

- Calvus – A tall cloud with a large, round, and puffy top. Found only in the genus cumulonimbus.

- Capillatus – A later-stage version of a calvus cloud, these clouds are large and have a mostly flat, anvil-shaped top. These clouds are only found in the genus cumulonimbus.

- Congestus – Very tall, puffy clouds that look a lot like a head of cauliflower. Found only in the genus cumulous.

Like with plants and animals, clouds are named by placing their genus name first, followed by the species name. So, you could have a cumulus congestus cloud or a cirrus fibratus cloud.

It’s sort of like a mitch-and-match system where you can pair a genus and species name together to create a type of cloud.

However, some genera and species name combinations either don’t exist or they’ve rarely been spotted in nature. For example, while you can have a cumulonimbus calvus or a cumulonimbus capillatus, a cumulonimbus fibratus doesn’t exist. But learning which genera and species names do go together is something that takes time and practice.

Cloud Varieties

In addition to genera and species, some clouds can be further described by variety. These varieties are somewhat similar to a subspecies when classifying animals and plants. For example, you can have a cirrus fibratus radiatus cloud or an altocumulus lenticularis duplicatus cloud.

As with cloud species, not all cloud species are associated with all the different cloud genera. Some cloud varieties also have more to do with the opacity of the cloud while others describe the pattern or texture of the cloud.

The primary cloud varieties that you might encounter include:

- Inortus – Curved, twisted, and tangled cloud wisps. Found in the genus cirrus.

- Undulatus – Forming wave-like features. Found only in the genera stratus and stratocumulus.

- Lacunosus – Patchwork-type clouds that have frayed edges, holes, and other broken features that disrupt their opacity. Found in the genera altocumulus and cirrocumulus.

- Vertebratus – Clouds that look like a skeleton with a thick central area and fibrous wisps extending out on either side. Found in the genus cirrus.

- Radiatus – A pattern of parallel bands of clouds. They often look like they converge together on the horizon. Found in the genera stratocumulus, altostratus, cirrus, and altocumulus.

- Duplicatus – Clouds that form in two or more large, horizontal layers that blend together to create a single large structure. Found in the genera cirrus, altostratus, altocumulus, and cirrostratus.

- Opacus – Very thick layers of clouds that block out much of the sun behind them. Found in the genera stratus, stratocumulus, altostratus, and altocumulus but does not include inherently opaque cloud genera such as cumulus and cumulonimbus.

- Perlucidus – Semi-transparent layers of clouds. Found in the genera stratocumulus and altocumulus.

- Translucidus – Thin, mostly translucent layers of clouds. Found in the genera stratus, altostratus, altocumulus, and stratocumulus.

Supplementary Features & Accessory Clouds

Finally, we can categorize clouds based on any supplementary features or accessory clouds that they might have.

Supplementary features and accessory clouds, however, are not necessarily an integral part of the cloud itself. These features and accessories simply modify the appearance of a cloud rather than change its structure, sort of like if we humans put on a new outfit. A jacket doesn’t change who we are as people, but it affects what we look like and how we’re perceived.

That being said, supplementary features and accessory clouds do often signify interesting atmospheric phenomena, such as large downdrafts of air or low humidity in the atmosphere. So, while they do not change the genera, species, or variety of a cloud, they are worth paying attention to if you want to understand the current weather conditions.

These supplementary features and accessory clouds include:

- Incus – Also known as an “anvil,” incus are associated with mature cumulonimbus clouds.

- Virga – Wispy features descending from the bottom of clouds indicating that the precipitation is evaporating before it hits the ground.

- Arcus – Large, thick, arch-shaped clouds associated with a cumulonimbus cloud at the front of a gust front. Sometimes called a shelf cloud.

- Tuba – Cone-shaped clouds that descend from the base of a cumulonimbus or cumulus cloud. Now more commonly called a funnel cloud. When it hits the ground, these clouds can manifest as tornadoes.

- Pileus – Frequently called a cap cloud, pileus are small accessory clouds that attach to the top of cumulonimbus or cumulus clouds.

- Mamma – Forming large, udder-shaped protuberances, mamma (mammatus) are found mostly on cumulonimbus, altostratus, altocumulus, stratocumulus, cirrocumulus, and cirrus clouds.

- Velum – Large, thin, horizontal accessory clouds that extend out from the main cloud in a veil-like fashion. These can occur with cumulonimbus and cumulus clouds.

- Pannus – Ragged-looking accessory clouds that form on the bottom of some clouds during periods of precipitation.

- Praecipitatio – Any cloud with precipitation that’s actively reaching the ground.

Do note that while many of these supplementary features and accessory clouds are not stand-alone cloud genera or species in their own right, they are commonly referred to as their own type of cloud.

For example, you may hear people talk about “mammatus clouds,” as we did in our list at the start of this article. While mamma are technically part of another type of cloud, the common usage of this term has evolved so much that we often think of it as its own type of cloud in non-scientific contexts.

Therefore, we’ve listed many of these supplementary features and accessory clouds as stand-alone cloud types in our list.

You may also like: The 9 Types of Weather that You Must Know and Where To Get Weather Forecast: Complete with Images, Facts, Descriptions, and More!

How Do Clouds Form

Although cloud spotting is a worthy activity in its own right, understanding how clouds form can help you better understand how to use clouds to track changes in the weather while you’re outside. Plus, knowing how clouds form can help you impress your friends when you’re out and about in the mountains.

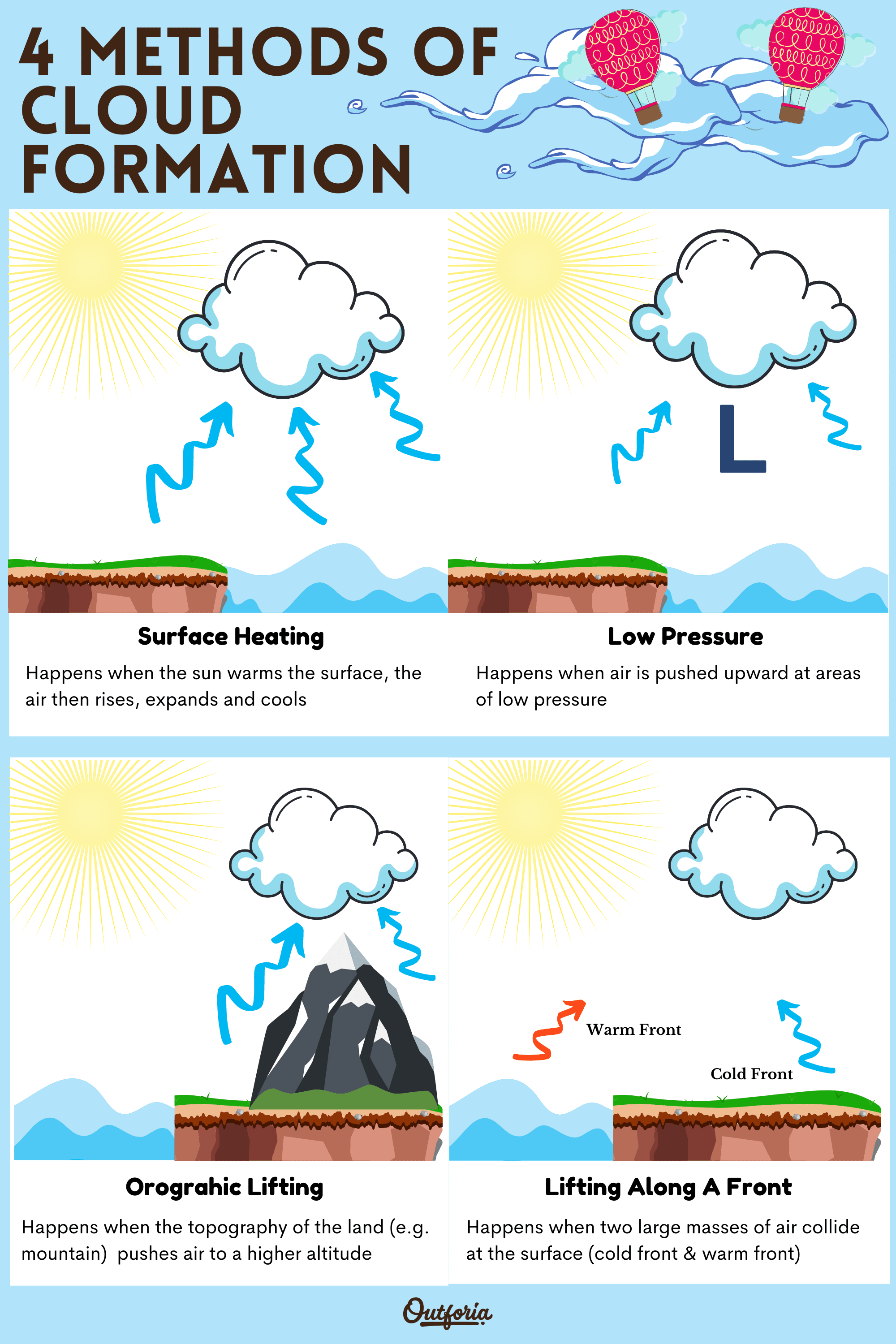

So, in this section, we’ll introduce you to four of the most common methods of cloud development. Although every instance of cloud formation is different, chances are pretty high that one or more of these four processes are involved whenever you see clouds in the sky.

Before we get into the details of how clouds form, there are a few key principles of meteorology that you ought to know. Many of these may already be familiar to you, but it’s important that we’re all on the same page before we start talking about cloud formation. These principles are:

- Hot air rises and cold air sinks

- Air moves from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure

- Cold air can hold less moisture than warm air

- When air rises in the troposphere, it cools and the water vapor in it condenses

We should note that, despite what we wrote in principle number three, air doesn’t technically “hold moisture.” However, this is the best way to conceptualize what’s happening in the atmosphere without the need to get into some pretty technical physics that’s beyond the scope of this article.

So, while you won’t hear a meteorologist talk about “air holding moisture,” this is a straightforward way to wrap your head around some tricky meteorological concepts.

With that in mind, let’s dive into the four methods of cloud formation!

Share This Image On Your Site

<a href="https://outforia.com/types-of-clouds/"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Cloud-Formation-Infographic-04211.png"></a><br>Cloud Formation Infographic by <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>Surface Heating

First up on our list of cloud formation methods is surface heating. To understand how this process works, we simply need to remember that every day, when the sun rises, it heats up the Earth’s surface.

As the sun heats the planet, the air at the surface of the Earth then rises relative to its surroundings. As the air rises, the air cools and any water vapor in the air mass condenses. Eventually, if enough of the moisture condenses into water droplets, we have a cloud. Pretty straightforward, right?

Since the sun rises every day, this process of cloud formation through surface heating happens on a regular basis.

In fact, if you’ve ever looked up in the sky in the afternoon of a sunny day, you’ve probably seen this process at work. When puffy cumulus clouds start to form in the afternoon of an otherwise bluebird day, surface heating is likely to blame.

However, when accompanied by other favorable atmospheric conditions, this process of surface heating can also lead to severe weather. Indeed, clouds that form during surface heating can eventually become cumulonimbus clouds that lead to isolated thunderstorms on a warm summer’s afternoon.

Low Pressure

Once you understand how clouds form through surface heating, you’re in a good position to understand how cloud formation through low pressure works, too.

As with air that’s heated by the sun, air that’s in a region of low pressure tends to rise up in the atmosphere. Once this air starts rising, it will cool, which will cause the water vapor in this parcel of air to condense into water droplets and form a cloud.

Therefore, just like air that’s heated at the Earth’s surface, air that’s forced upward through a region of low pressure will rise, cool, and condense into a cloud.

So, anytime you hear a weather forecaster talking about a low pressure system, you can reasonably expect that clouds will be in the forecast, too.

Orographic Lifting

Up until now, the two different types of cloud formation that we’ve discussed have both had to do with changes in the temperature or pressure of an air parcel. But, the surface of the Earth can also have a major impact on cloud development and on the weather as a whole.

For example, imagine a large mountain chain like the Rocky Mountains in the western United States. If the wind is blowing from the west and it encounters the western slope of the Rockies, the mountains will actually force the air to be pushed up the western slope of the range.

As the air gets forced up the windward side of the mountain, it eventually rises, cools, and condenses to form a cloud—just like what we saw with the formation of clouds through surface heating and low pressure.

This upward forcing of the air is called orographic lifting, which is basically a fancy term for when the topography of the land pushes air to a higher altitude. This process often forms stratus clouds and lenticular clouds, especially on warm, sunny days in the summer months.

Lifting Along A Front

Our fourth and final method of cloud formation is lifting along a front. To understand how this process works, you’ll first need a good working knowledge of what a weather front actually is.

You’ve likely heard weather forecasters talk about “approaching cold fronts,” but what actually is a front, you might ask?

Essentially, a front is the boundary between any two air masses. While you won’t necessarily see these air masses if you look up at the sky, our troposphere is composed of large parcels of different air, each of which has a distinct temperature and moisture content, and each of which is constantly moving around the Earth’s surface.

For example, some air masses are warm and moist, such as those that originate over the subtropical waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Other air masses, such as those that originate over the frigid lands of Arctic Canada, are cold and dry.

When two air masses with different temperatures and moisture contents meet, their meeting point is called a front. If a mass of warm air is advancing over a mass of cold air, we would call this a warm front. Meanwhile, if a mass of cold air is advancing over a mass of warm air, we’d call that a cold front.

Now that you understand what a front is, let’s get back to the good stuff: clouds.

So, as one air mass advances on another, it forms a front. This frontal boundary acts a whole lot like an invisible wall for an air parcel, forcing air at the bottom of the frontal boundary higher into the troposphere. As this air moves upward, it rises, cools, and condenses to form a cloud.

It is worth noting that some fronts, namely cold fronts, are more likely to create severe weather as a result of this cloud formation.

Since cold air is denser than warm air, cold air behind a cold front rapidly pushes the warm air in front of it high up into the atmosphere. This warm, moist air is already primed for a storm, so cold fronts are often associated with lines of major thunderstorms and cumulonimbus clouds.

You may also like: What Is A Tornado? Facts & Full Guide To Understanding Twisters

Clouds FAQs

Here are our answers to some of your top questions about clouds:

Is Fog A Cloud?

Yes, fog is technically a cloud that’s located at ground level. Since both clouds and fog are essentially condensed water vapor, the only difference between them is that fog touches the ground.

But, we don’t generally classify fog alongside all the other types of clouds. Instead, the different types of fog are usually categorized as a separate type of atmospheric phenomena.

What Are The Big Fluffy Clouds Called?

If you see big fluffy clouds overhead, you’re probably looking at cumulus clouds. Cumulus clouds are defined by their puffy, cotton candy-esque shape, so they’re what most people are thinking of when they picture a fluffy cloud.

What Is The Highest Type Of Cloud?

Noctilucent clouds are the highest type of cloud in Earth’s atmosphere. These clouds are found in the mesosphere, which is about 31 to 53 miles (50 to 85 km) over the surface of the Earth. However, these clouds are very rare, and they are generally only seen in the high latitudes during the summer months.

What Is The Most Dangerous Cloud?

Cumulonimbus clouds are arguably the most dangerous clouds. Although not all cumulonimbus clouds will create severe weather, many will create lightning, large hail, strong winds, and even tornadoes, all of which can cause property damage or serious injury.