Today, Lake Michigan is known as an excellent freshwater sportfishing destination. In the early days of the United States, the lake was bursting with trout species and native fish species numbering so many that they would seemingly never run out.

In between those times, the ecology of the lake collapsed, forcing management programs to introduce new species and try to give native fish a chance to reclaim their territory.

Whether you want to learn about the ecological history of Lake Michigan or are an avid angler, you’ll love reading this article discussing twenty of the most important fish in Lake Michigan.

share this image on your site

<a href="https://outforia.com/fish-in-lake-michigan/"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/fish-in-lake-michigan-infographics.jpg"></a><br> fish in Lake Michigann <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>

You may also like: Know the 5 Popular Lakes For Trout Fishing in Michigan and Different Kinds of Trouts You Can Find

20 Most Common Fish in Lake Michigan

1. Chinook Salmon

Chinook salmon, also known as king salmon, were introduced to the Great Lakes starting in 1877 and became an established species by 1967. They were brought to Lake Michigan as part of a biodiversity rehabilitation program.

King salmon grow to lengths between 20-35 inches (51-89 cm) and weigh up to 35 pounds (16 kg). The Wisconsin state record fish of over 43 pounds (19.5 kg) was caught in Lake Michigan. They typically have silver sides, a white belly, and a blue to blue-green iridescent stripe on their backs. You tell them apart from other salmon by their black gums and mouths.

Native to the Pacific Ocean and reliant on moving between the ocean and freshwater for breeding, the king salmon of Lake Michigan have no successful reproduction. Instead, their numbers are replenished by yearly restocking by wildlife agencies. More on how that is done later.

As adults, only lampreys and humans are considered predators for these large fish. Most often, the salmon spend their time in open-water areas of the lakes in depths less than 100 feet (30 meters).

2. Coho Salmon

Coho salmon are another salmon species introduced to the Great Lakes at the same time as king salmon.

Coho salmon grow to lengths between 11-26 inches (28-66 cm) and usually weigh up to 12 pounds (5.4 kg). While similar in coloration to king salmon, you can tell coho salmon apart by their white gums, a slightly forked tail, and 12-15 rays in their anal fin.

Coho salmon are also native to the Pacific Ocean. Like the king salmon, they struggle with successful reproduction in their lake environment and are continually stocked in the lake through hatchery programs.

Adults have few natural predators, only a few larger fish, humans, and lampreys are known to feed on them. Coho salmon spend most of their time in the open areas of the lake, moving into the streams and shallower areas of their birth beginning in the Fall.

3. Steelhead

Steelhead and rainbow trout are essentially the same species, with steelheads being the variation that is native to coastal saltwater environments. The species are stocked in Lake Michigan, which serves as the ocean environment for the species. They travel to the streams and tributaries of the lakes to reproduce, then head back out into the lake.

The three steelhead strains of Lake Michigan grow on average to lengths up to 30 inches (76.2 cm) and can weigh up to 12 pounds (5.4 kg). Steelheads have a salmon-like body shape, with a white belly, silver sides, and a green back. They have a purely white mouth and distinct radiating patterns of spots on their tails.

The species is native to the Western United States and spends most of its time in coastal, saltwater environments. Unlike salmon species, they do not die after reproducing. Steelheads regularly travel back to the sea after laying eggs in freshwater, though most individuals only reproduce one or two times in their life cycle.

Adults travel towards streams when the weather cools down, away from their open-water hunting grounds. Steelheads typically spawn after they reach four to five years of age.

4. Rainbow Trout

Just like their near-identical cousins the steelhead, rainbow trout can be found in Lake Michigan. Rainbow trout are the variation of the species that spend their entire lives in freshwater naturally.

You can generally tell the two species apart by their size and color. Rainbow trout tend to be smaller, growing up to 20 pounds (9 kg) on average in lakes and only 5 pounds (2 kg) in rivers. They tend to have paler coloring than steelheads, with more muted spots and they lack the shiny nature of steelheads.

Since they share the same habitat and are essentially the same species, rainbow trout and steelheads are hard to tell apart, grow to similar sizes, and tend to have similar behavior. The major difference between the strains in Lake Michigan is their ancestor’s heritage.

5. Brown Trout

Brown trout were brought to North America in the 1800s from Europe and Western Asia. Today, they’re found throughout the continent from Canada and the eastern United States to the West Coast.

Brown trout in Lake Michigan are typically a silver color with an X-shaped marking on their back, white mouths, spots along their bodies, and a square tail. While spawning, they change color and take on a tan to reddish-brown color with brighter red or black spots.

Average brown trout reach lengths between 16-30 inches (40-76 cm) and weigh up to 16 pounds (7.2 kg). Like other trout species, roughly one million individuals are stocked into Lake Michigan annually.

Most of the time, you can find them between 2-5 miles (3-8 km) offshore in water 15-70 feet (4.5-21 meters) deep. They’re known as skittish fish that will spook easily, and most fish are caught while trolling lures through their ideal depths.

6. Brook Trout

Brook trout are native trout species that can be found along the shorelines of Lake Michigan and in the streams and tributaries around the lake.

On average, brook trout reach lengths between 10-20 inches (25-51 cm)and weigh up to 4 pounds (1.8 kg). They have a dark green or brown back, red spots surrounded by bluish halos, and reddish fins on their undersides.

Around 200,000 brook trout are stocked into Lake Michigan each year, as the streams surrounding Lake Michigan are too warm for successful spawning. River mouths and rocky shorelines are the favorite habitats of brook trout in the area, but they can be found throughout the lake and at many depths.

7. Lake Trout

Lake trout were once one of the most plentiful fish found in Lake Michigan, but they were essentially deemed extinct in Lake Michigan by 1956. Their disappearance was the motivator behind the Great Lakes Rehabilitation Program that introduced a number of fish species and aimed to repopulate lost native fish.

Lake trout grow to lengths between 17-36 inches (43-91 cm) and weigh up to 30 pounds (13 kg) in most instances. They tend to vary in color from light green or gray to black. Most individuals have light spots and worm-shaped markings along their backs and sides.

While they are a native species, over a million lake trout are stocked into Lake Michigan each year. This is because the species has not successfully re-established itself in a way that it can reproduce consistently. Most lake trout spend their time in the water over 80 feet (25 meters) in depth.

8. Largemouth Bass

Largemouth bass are the largest member of the sunfish family and can be found throughout Lake Michigan around underwater structures of all kinds.

They tend to have a green or dark-colored back, and greenish or yellow sides and bellies. You can tell largemouth and smallmouth bass apart by their mouths, with the largemouth’s upper jaw further back on the face beyond their eyes.

On average, largemouth bass reach lengths of between 6-16 inches (15-40 cm) and weigh up to 7 pounds (3.1 kg). They’re seldom found in water over 20 feet (6 meters) in depth and school with up to five individuals. Most often they hide around sunken logs, under lily pads, or around rocky outcrops and mounts. In colder weather, they move to deeper waters.

Young bass are prey for larger predator fish such as muskellunge, walleye, northern pike, and perch. They tend to feed on a variety of smaller fish such as minnows and shad, as well as invertebrates, insects, and amphibians.

The big reason why muskies are considered hard to catch is how hard they are to hook. They have plated mouths that don’t allow hooks to set easily and can be incredibly frustrating because of how hard they can be to trick.

Their incredible eyesight and difficulty to hook have earned muskies the nickname “the fish of a thousand casts” in sportfishing circles. These ambush predators sit in grass beds and leap out to strike at unwitting prey animals.

9. Walleye

Walleye get their name from their distinct eyes which have a film over them that gives them a glassy-eyed appearance. This film helps them see better in low-light conditions and hunt at night when walleye are most active.

Walleye are mostly silver in color and are a larger species in the perch family. They grow to lengths between 2.5 – 3 feet (0.75 – 0.9 meters) and can reach weights of 10 – 20 pounds (4.5 – 9 kilograms).

They’re found throughout Lake Michigan, tending to stay in deeper waters during cooler weather. Walleye are a popular ice-fishing target and will readily strike spoons and other lures that look like the smaller fish they prefer to feed on.

10. Northern Pike

Related to the musky, northern pike are a gluttonous native species in Lake Michigan. Like other species, their numbers have suffered from overfishing and invasive species, but rehabilitation programs have proven to increase populations.

Northern Pike are tubular fish that have a duckbill-shaped mouth, a streamlined body that makes it one of the fastest-swimming fish in the lake, and sharp cone-shaped teeth. You can tell them apart from muskies by their cheeks being covered in scales, their lighter markings shaped like beans, and rounded fins.

Most northern pikes are around 10-20 inches (25-50 cm) and weigh up to 4 pounds (1.8 kg), but exceptional individuals can grow to 37 inches in length. They prefer shallower water and are most often found in grass beds in warmer weather. When it gets cold, they head towards the bottom of the lake for cooler water.

Northern pike eat almost anything they can swallow, from shrews to frogs and smaller fish to other pikes. They’ve even been known to die from choking on a prey item too big for them to eat.

11. Muskellunge

Muskellunge or muskies are known in the sportfishing world as one of the hardest to catch freshwater fish in the world. They grow up to 44 inches (112 cm) and have been known to weigh as much as 50 pounds (22.6 kg).

Musky and pike have very similar body types, both are streamlined tubes, both have intimidating teeth, and both have pointed jaws. You can tell a musky apart from a northern pike by its tiger-striped sides, pointed fins, and half-scaled cheeks.

Muskies are the top predator in most northern freshwater environments. They feed on anything they can swallow or tear apart on a strike including fish, birds, small mammals, and amphibians.

12. Lake Sturgeon

Sturgeon are true living fossils and the lake sturgeon of Lake Michigan are no exception. These fish have changed very little since they took the world stage over 100 million years ago. Sturgeon are known for a long life span and slow growth rate but can reach lengths of over 70 inches (177 cm) and weights of over 200 pounds (90 kg).

Sturgeon retains many features that other fish evolved out of. They have a heavy, torpedo-shaped body, bony plates resembling armor, and almost resemble sharks. Most lake sturgeon have white undersides and a black, gray, or greenish back.

These bottom-dwelling fish use barbels to sense small creatures like invertebrates on the muddy lake floor. They have no teeth and small mouths, making them suction feeders that can only take small prey items. Most of their time is spent in less than 30 feet (10 meters) of water, however, they can be found in deeper areas of Lake Michigan as well.

Revered by native groups, lake sturgeon tended to have solid populations and a kind of protection for a long time. More modern fishermen thought of them as nuisance fish and killed off much of the population before their value for caviar, meat, and other products were discovered. Once this was known, sturgeon became the target of harsh overfishing.

13. Yellow Perch

Yellow perch tend to be targeted by fishermen more because of how tasty they are than how much of a fight they put up. These 7-10 inch (18-25 cm) long fish have yellow colorations on their sides and greenish backs.

Perch are one of the most common fish in Lake Michigan, found throughout the lake in shallow and deep water environments. They’re an important prey species for larger predatory fish and are very adaptive to a variety of water conditions.

Smaller perch feed on insects, larvae, and zooplankton, but minnows make up most of a fully-grown perch’s diet.

Unlike some other fish species, perch tend to be overpopulated in the Great Lakes. This is due to their high reproductive rate and overfishing of predator species. Management of yellow perch mostly involves the stocking of predator species such as bass, walleye, pike, and salmonids.

14. Whitefish

Lake whitefish get their name from their pale coloration. You can identify them by their size, silver to olive color, and the fact that their upper jaw overhangs their lower one. Their tails have an extreme fork to help them swim faster and their fins have a darkened edge.

Lake whitefish school in large numbers and tend to hang around depths of up to 200 feet (61 meters). On average, whitefish are around 12 inches in length (30 cm) and weigh around 4 pounds (1.8 kg). Despite this, they can grow to be much larger with the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) record for lake whitefish standing at 14 pounds (6.3 kg).

Juvenile whitefish can be found along shorelines and in shallow water where they feed and grow. Once they reach adulthood, they travel to the deepest regions of the lake and school in large numbers.

Whitefish is a target species for many predator fish in Lake Michigan. Their diet mostly consists of insects, shrimp, eggs, and tiny fish.

15. Catfish

Lake Michigan is home to a host of different catfish species including channel catfish, flathead catfish, and three species of bullhead catfish.

Catfish are easily identified by their scaleless bodies, long barbels around the mouths, and lack of teeth. The species in Lake Michigan range in size from a pound or two up to nearly 80 pounds (36 kg)!

Most catfish live in holes on the bottom or on the sides of the shoreline. You’ll find catfish at nearly any depth, but especially in areas where currents in the lake will push prey species to them such as lake mounts, points, and areas of structure. They’re voracious feeders that will eat nearly anything they can suck into their mouths and swallow.

16. Crappie

Both black and white crappie can be found in Lake Michigan. These panfish are a sought-after sport fish that’s easily accessible for anglers of any skill level.

Crappies have tall, thin bodies and can vary from light to dark coloration.

Black crappies tend to have dark, irregular blotches on their bodies. You’ll mostly find them close to shore and hiding in dense areas of vegetation or structure.

White crappies tend to have dark vertical stripes and spots on their sides. You’ll mostly find them in open-water areas.

Both species are highly social. They school in large numbers and form large nesting colonies with closely-packed nests during the breeding season. Most of a crappie’s diet consists of very small fish, zooplankton, crustaceans, and insects.

An average crappie of either species is only around 12 inches (30 cm) in length and weighs under one pound (0.45 kg).

17. Sea Lamprey

Sea lampreys are an incredibly damaging invasive species that can be found in all of the Great Lakes. While normally a marine species, lampreys were able to navigate through rivers and into the Great Lakes. Like some other species, they go into rivers to spawn. Once lampreys were trapped in the lakes, they adapted to the environment and stayed.

Lampreys have an eel-like body and a large rounded mouth. Inside the mouth are sharp, curved teeth and a sharp tough used to cut into prey animals. Landlocked lampreys grow to around 25 inches (64 cm) in length.

Juvenile lampreys are filter feeders that burrow into sediment and remain there for up to ten years. Adult lampreys are parasitic. They use their mouths to suction onto fish or other animals in the water and then suck blood from the host.

Lampreys are a problem because, in freshwater environments, they kill their host. In the ocean, they evolved side by side with fish and the host rarely dies because of them. In the Great Lakes, these animals reduced fish populations even before humans overfished them.

Sea lampreys entered the Great Lakes because of human ingenuity. Niagara Falls used to be as far as they could go upriver, however, the building of the Welland Canal bypassed that obstacle and gave lampreys access to the lakes.

With their incredibly fast reproductive potential, lampreys at one time essentially took over Lake Michigan. Pesticides were developed that harmed lampreys but not other aquatic species. These target larval and juvenile lampreys in tributaries around the Great Lakes and are administered roughly every four years.

Lampricides in combination with traps and barriers along travel routes have led to a downturn in lamprey populations within all of the Great Lakes.

18. Rainbow Smelt

Rainbow smelt isn’t native to Lake Michigan, but they are native to the Northern Atlantic Coast. In 1912, the fish were stocked in Crystal Lake, Michigan, and eventually made their way into Lake Michigan itself.

Smelt have similar body shapes to trout and salmon, but much much smaller. Rainbow smelt have a long thin body with purple, pink, and blue iridescent sides. Adults grow to reach lengths between 3-6 inches (7.5-16 cm).

Crustaceans and minnows make up most of a rainbow smelt’s diet. They also love insect larvae, the primary bait used for hook-and-line fishing for the species. Sensitive to light and temperature, they spend most of their time in the mid-water of the lake but will descend to the bottom during bright daylight hours.

Environmentally, rainbow smelt is a great prey species for introduced salmon species. These introduced predator populations have mostly kept rainbow smelt populations in check. They do compete with native yellow perch for food, but they don’t seem to have large impacts on perch populations.

19. Alewife

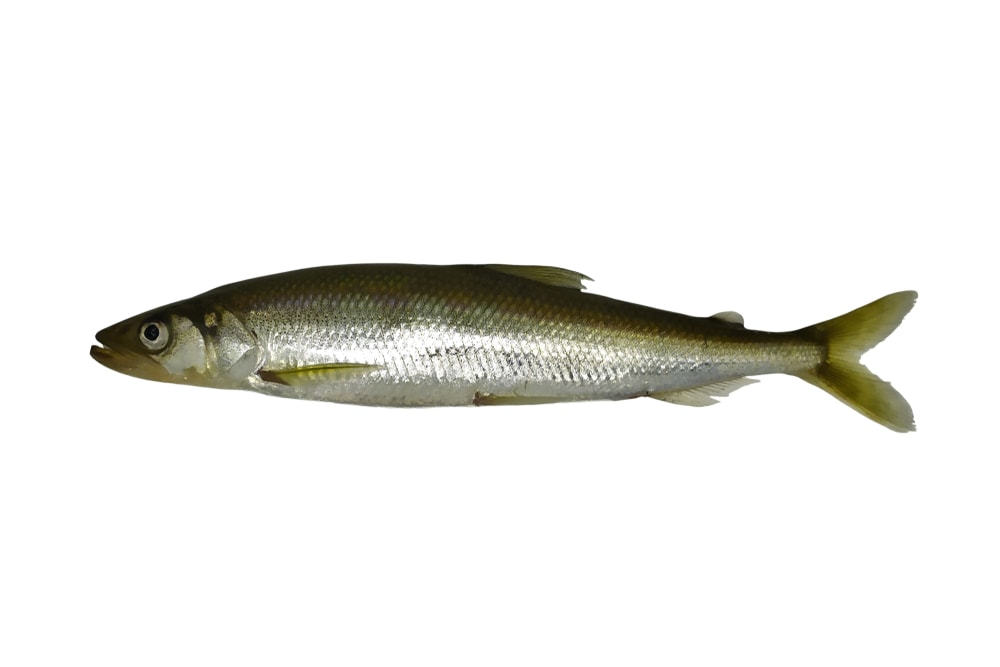

Alewives are an anadromous species of herring and are known as a shad species in North America. They were introduced to the Great Lakes through the Welland Canal and accidental introduction by boat ballast tanks.

Alewives are important for predator species in the Great Lakes and make up a significant portion of salmon and trout diets. The small silver fish have a chunky body and reach average lengths around 10 inches (25 cm).

Alewives are credited with the decline of many species in the Great Lakes. Their consumption of zooplankton and fish eggs has the most to do with this. Surprisingly, alewives can exhibit seasonal “die-offs,” where large schools suddenly die and wash up on shorelines.

20. Round Goby

Ballast water from ships is blamed most often for the invasion of the round goby in the Great Lakes. This small fish is a voracious predator, able to outcompete native fish for resources.

Round gobies do most of their damage thanks to their appetite. To put it simply, they eat a lot. The problem is that these fish eat other fish eggs, adding pressure to populations of other species in the lakes. This extends to the predator fish that have adapted to feed on the gobies.

Essentially every predator fish outside of chinook salmon has learned to feed on round gobies, but it doesn’t seem to lower their population. This is mostly due to their ability to outcompete other fish in their niche and the fact that they breed so quickly. A round goby can breed multiple times per year, laying hundreds of eggs.

On average, a round goby will only reach around 10 inches (25 cm) in length. They are usually a dark gray or mottled color and seem flattened on their bellies. Gobies can be found at any depth and are usually picking around the lake bed for food.

You may also like: Know The Different Ways on How Sharks Mate: With Images, Facts, and Chart!

The Introduction of Predator Fish Species to Lake Michigan

By the mid-1950s the Great Lakes were all full of invasive fish species and most of the native species were either nearly extinct or no longer in the lakes. There were a variety of causes for these problems, from invasive species like alewives and sea lampreys to overfishing.

Beginning in the 1960s, state governments began to introduce predator species to the Great Lakes. Salmon were selected because they were able to become a top predator in the lakes and reduce alewife populations. Lampreycides and better barriers for invasive species were put in place along rivers.

The introduction of species led to a booming sportfishing industry and a new environmental balance among fish species in the Great Lakes. Overall, these introductions could be called successful, as even native species have found a foothold again in the years since.

The problems in the Great Lakes are not solved. Lake trout, salmon species, and other fish have had little success reproducing in the Great Lakes. They move to tributaries to spawn, but their efforts are largely unsuccessful.

I’ll explain very simply how wildlife management programs keep fish stocked in the lakes. What happens nowadays is that eggs are collected from tributaries by state programs, hatched in hatchery facilities, and then grown until the juvenile fish are large enough to survive. Those fish eventually return to the tributary their eggs were laid in to lay their eggs and the cycle continues.

Millions of fish are stocked into the Great Lakes each year to keep population levels where they need to be. Most fish don’t have the ability to leave the Great Lakes along traditional routes. Some species like lake trout have had limited success in actually hatching the eggs they spawn, but overall, most of the fish in the lake are released from government hatcheries.

The system is not perfect, however, continued efforts have led to a fairly balanced ecology and given the introduced and re-introduced fish species the opportunity to adapt and reproduce on their own.

You may also like: Learn the Different Types of Eels You Can Find on Earth: With Images, Facts, and More!

Sportfishing and Why It Matters

Sportfishing and fishing in general tends to get a bad rap. While there are a lot of dishonest people out there that can do a lot of harm to an ecosystem, the majority of anglers are the ones that follow rules and respect the sport.

When it comes to environmental damage it’s commercial fishing, not recreational, that does the most harm. That doesn’t absolve anglers from their responsibility to care for the animals they fish for, it’s simply a fact that their impact has less weight behind it than a commercial operation.

Licenses, fishing gear, boat ramp fees, and other sales all bring in money that supports native wildlife rather than destroying it. State governments, especially around the Great Lakes, operate programs that stock fish into the lakes, care for eggs and juveniles, manage invasive species, and clean pollutants from the environment.

Most states have no allocation of funds for wildlife management. The entire budget is paid for by license sales, donations, or federal grants. You can read about how that works in Minnesota here.

The thing that may surprise a lot of people is that hunters and fishers actively contribute to the conservation of our remaining wild areas more than other groups. This goes as far as voting in favor of additional taxes on specific sales so that that money goes directly towards wildlife management programs.

With the loss of trout populations in Lake Michigan in the mid-1900s, the surrounding areas lost a lot of money, jobs, and resources. The introduction of fish species like salmon and the continued efforts to restock native species such as lake trout brought those back.

It also brought in an incredible opportunity for freshwater sport fishermen. Those anglers in turn contribute the funds to keep the programs running. While not always successful, these programs have breathed life back into the Great Lakes, corrected many mistakes because of human activity, and helped save communities in the areas all at once.

I would urge readers who care about the devastation of our environments to turn their anger and energy towards putting pressure on government officials to do more and on commercial operations to limit their damage. Sportfishing matters and in fact, the way it conserves resources vastly outstrips any damage it could potentially do.

You may also like:

Discover the different species found in Michigan here:

Turtles In Michigan | Snakes In Michigan | Frogs Of Michigan | Woodpeckers In Michigan | Michigan Water Snakes | Hawks In Michigan | Michigan Birds | Owls In Michigan