Home to some of the hottest, coldest, driest, and harshest environments on Earth, deserts are a must-visit for any outdoor adventurer.

However, while we often think of deserts as massive areas of sand, stretching out for as far as the eye can see, it turns out that there are many different types of deserts out there, each with their own unique characteristics.

Up next, we’ll introduce you to the 12 different types of deserts and what makes them special so you can wow your friends and family with your desert knowledge on all your upcoming adventures.

What Is A Desert?

First things first: What is a desert?

According to National Geographic, a desert is any area that gets less than 10 inches (25 centimeters) of precipitation each year. All deserts operate on what’s known as a ‘moisture deficit,’ which is just a fancy way of saying that they lose more moisture each year through evaporation than they receive from precipitation.

Notice that this definition doesn’t say anything about temperature? That’s on purpose.

In fact, while we often think of deserts as very hot places, there are quite a few cold deserts on Earth that boast brutally frigid daytime and nighttime temperatures (more on that in a bit).

So, a desert is simply any place that doesn’t get a whole lot of precipitation. Deserts are actually found on every single one of Earth’s continents and they cover an estimated one-fifth of our planet’s total land area. Who knew?

Ultimately, a working knowledge of this definition is essential for understanding the different types of deserts, which we can classify by geography or by aridity and temperature.

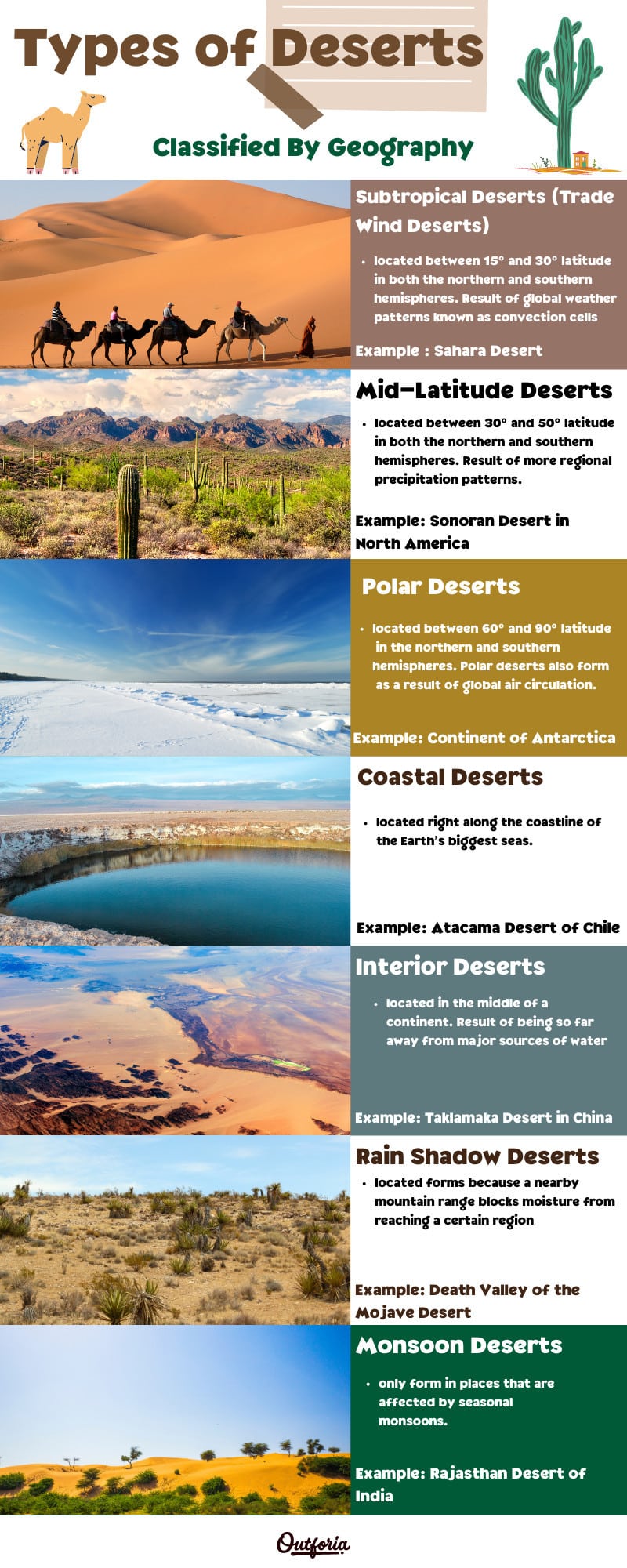

Deserts Classified By Geography

Share this Image On Your Site

<a href="https://outforia.com/types-of-deserts/"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Types-of-desert-Infographic.jpg"></a><br> Types of Deserts Infographic by <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>One of the primary ways that eremologists (someone who studies deserts) classify deserts is by their geography.

The Earth’s deserts tend to form in certain geographical areas which have various climatic features or geologic formations that help deserts grow and flourish. There are 7 commonly used types of geographically-classified deserts that any outdoor adventurer should know.

Subtropical Deserts (Trade Wind Deserts)

If you were to picture a desert in your mind, you’d almost certainly imagine a subtropical desert. Subtropical deserts, which are also known as trade wind deserts, are, as the name suggests, located in the world’s subtropical regions.

By definition, this means that they’re located between 15º and 30º latitude in both the northern and southern hemispheres. Or, in other words, they’re located around the Tropic of Cancer in the northern hemisphere and around the Tropic of Capricorn in the southern hemisphere.

The Sahara Desert of Africa is perhaps the best example of a subtropical desert. It is nearly the size of the continental United States, covering an area of about 3.3 million square miles (8.6 million square kilometers).

However, a desert this size doesn’t form by accident. Instead, these subtropical deserts are the result of global weather patterns known as convection cells, which help drive some of the Earth’s major climatic systems.

For more information on how these convection cells create subtropical deserts like the Sahara, check out this video from the UK Met Office:

Mid-Latitude Deserts

While subtropical deserts are, well, located just outside the tropics, mid-latitude deserts are located at the mid-latitudes.

The mid-latitudes are generally defined as existing between 30º and 50º latitude in both the northern and southern hemispheres. However, unlike subtropical deserts, which are formed as a result of global circulation patterns, mid-latitude deserts are generally the result of more regional precipitation patterns.

Indeed, most mid-latitude deserts, such as the Sonoran Desert in North America, are either located far from a major body of water or they’re located in the rain shadow of a lofty mountain range. Both of these characteristics limit the amount of moisture that reaches an area, preventing significant precipitation.

These deserts can be very hot (the Sonoran Desert can have temperatures up to 118ºF/48ºC), but the defining characteristic of mid-latitude deserts is their geographic location.

Polar Deserts

As you can probably surmise from the name, polar deserts are located in the polar regions, or, in other words, between 60º and 90º latitude in the northern and southern hemispheres. Like subtropical deserts, polar deserts also form as a result of global air circulation.

While it may come as a surprise, the main portion of the continent of Antarctica (excluding the Antarctic Peninsula) is actually a desert. Yep, even though Antarctica routinely records some of the coldest temperatures on Earth it is considered to be a desert landscape.

What about all the snow and ice on the ground, you might ask?

Well, although it’s true that most of the main continent of Antarctica is covered in ice and snow, this ice and snow formed many thousands of years ago. Indeed, the ice and snow that we see on the continent of Antarctica has been around for around 20 million years.

So, while we often hear about the great blizzards that sweep across the Antarctic ice sheet, it’s important to note that this generally isn’t freshly fallen snow. Rather, these blizzards are caused by high winds that churn up snow on the surface of the ice sheet and blow it around, causing decreased visibility and some truly frigid temperatures. Brr!

Coastal Deserts

When you think of a desert, you likely imagine a place that’s far from the ocean. However, there are quite a few coastal deserts which are located right along the coastline of the Earth’s biggest seas.

Perhaps the most famous coastal desert is the Atacama Desert of Chile. The Atacama is about 600 to 700 miles (1,000 to 1,000km) long and it’s sandwiched between the Andes and the Pacific Ocean. Here, the climate is so dry that some weather stations in the region have never record a single drop of rain!

How does a desert like this form next to an ocean, you might ask?

While we often think of coastal regions as moist environments, some places, like the Atacama region of Chile, are located near large currents that drive cold water up to the surface of the ocean.

In Chile, in particular, this current is known as the Humboldt or Peru current, and it’s responsible for creating a funky climatic situation called a thermal inversion where there’s colder air at sea level than there is at higher elevations.

Oftentimes, these thermal inversions result in widespread cloud formations and fog, but little, if any rain. The Atacama is actually the driest desert on Earth as the desert can go more than 20 years without a single millimeter of rain!

So, as crazy as it might sound, a cold ocean current can create a stifling hot and exceptionally dry desert in a coastal region, like the Atacama.

Interior Deserts

Standing in direct contrast to coastal deserts, interior deserts are located in the middle of a continent. These deserts generally form because they are so far away from major sources of water, such as the ocean, that there’s little, if any moisture in the air by the time it reaches that area.

There are quite a few interior deserts out there, including the Taklamakan Desert in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The Taklamakan is about 130,000 square miles (337,000 sq. km) in area, which makes it nearly the size of Germany. In some parts, the desert is thousands of miles from the nearest major body of water.

Interior deserts can be exceptionally dry and some, like the Taklamakan, are home to massive sand dunes. Some of these sand dunes can reach hundreds of feet in height, though they’re always shifting and changing in the wind.

Rain Shadow Deserts

A rain shadow desert is any desert that forms because a nearby mountain range blocks moisture from reaching a certain region.

Many of the Earth’s major mountain ranges have an associated rain shadow desert, including Death Valley of the Mojave Desert, which is in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada and other nearby ranges.

As we’ve mentioned, these rain shadow deserts form because some mountain ranges are so tall that they disrupt the natural movement of air masses from one place to the next.

These tall mountain ranges cause air masses to rise, cool, and condense, leading to widespread precipitation on the windward side of the range and very arid conditions on the leeward side of the range.

For more information and a visual representation of how the rainshadow effect works, check out this video from the University of Illinois:

Monsoon Deserts

Our last geographic category of desert is the monsoon desert. These deserts, which include the Rajasthan Desert of India and the Thar Desert of Pakistan, are often left out of lists of the main “types of deserts,” simply because they’re not very common.

In many ways, monsoon deserts are similar to both interior deserts because they form in the interior regions of continents, but what makes them unique is that they only form in places that are affected by seasonal monsoons.

Monsoons form annually in places such as India because of the differential heating and cooling speeds of land and water. While land can heat and cool very quickly, the temperature of major bodies of water changes quite slowly (this is due to something called specific heat).

Long story short, these different heating rates result in seasonal prevailing wind shifts and in an annual event known as the monsoon, which can bring massive amounts of water to the Indian subcontinent and the surrounding region.

Monsoon deserts then form in very far inland regions which are blocked by mountain ranges and, as a result, don’t get much of the monsoon’s moisture. The 2 monsoon deserts that we mentioned earlier (the Rajasthan and Thar) are located on the inland side of the Aravalli Range, so they get very little moisture from the annual monsoon.

If you want to learn more about how monsoons form, watch this great video from the UK Met Office:

You may also like: 22 Animals That Live In The Desert: How Do They Adapt?

Deserts Classified By Aridity & Temperature

So far, we’ve discussed 7 different types of deserts, which can be classified by their geographic location. However, we can also classify many of these same deserts by their aridity or temperature.

Hot and Dry Deserts (Arid Deserts)

Aptly named, hot and dry deserts (also known as arid deserts) are, well, hot and dry. Hot and dry deserts in North America include the Mojave Desert, the Chihuahuan Desert, and the Sonoran Deserts while other examples around the world include the Rub’ al Khali in Saudi Arabia.

In these deserts, extreme high temperatures can reach upwards of 120ºF (49ºC) or even higher, with the highest temperatures ever recorded in Death Valley hitting a scorching 134ºF (56.7ºC) in 1913.

Meanwhile, the Rub’ al Khali is considered to be a hyper-arid desert with a maximum precipitation average of about 1 inch (2.54cm) of rain each year and daily high temperatures regularly reaching an astonishing 123ºF (51ºC) during the summer months.

Semi-Arid Deserts

Semi-arid deserts are very similar to hot and dry deserts, but they tend to get slightly more rainfall. These deserts often have a steppe climate, which means that they support grasslands, sagebrush, and other similar types of vegetation.

Perhaps the best example of a semi-arid desert in North America is the Great Basin, which covers much of Nevada.

Depending on where you are in the world, the daily high temperatures of most semi-arid deserts generally doesn’t exceed about 100ºF (38ºC) in the summer months. The winter months can actually be quite chilly and snowfall is possible, particularly at higher elevations.

What really differentiates semi-arid deserts from hot and dry deserts, however, is their rainfall totals. Most semi-arid deserts will receive up to 1.5 inches (4cm) of precipitation each year.

Although this might not seem like much more than what you’d find in an arid desert, this extra bit of rainfall does make a huge difference in terms of what types of ecosystems you can find in a semi-arid desert.

Temperate Deserts & Cold Deserts

The final type of temperature-classified desert is the temperate or ‘cold’ desert. As you can deduce from the name, these deserts are much colder than their arid and semi-arid counterparts, though their daytime temperatures vary widely throughout the year.

Examples of temperate deserts include the Gobi Desert in eastern Asia, while the best example of a truly cold desert is the main part of the continent of Antarctica.

Temperatures in these regions can get very, very cold with average wintertime lows in the Gobi Desert reaching -40ºF (-40ºC) and a record low surface temperature of -128ºF (-89.2ºC) in Antarctica.

Since these places are deserts, they don’t receive very much precipitation, though you can sometimes see annual rainfall totals in cold deserts around 3.5 inches (9cm).

You may also like: 24 Different Types of Clouds with Pictures, Cloud Formations, Infographic and More!

Other Types Of Deserts

In addition to the 10 types of geographical and climate-classified deserts that we’ve discussed, there are 2 more types of deserts that don’t quite fit in anywhere else: the paleodesert and the extraterrestrial desert.

Paleodeserts

According to the USGS, a paleodesert is any large area of sand (known as a sand sea) that’s now considered to be ‘inactive.’

In a geologic sense, an active sand desert is one whose sands shift around in the wind, forming dunes and other features. Over millions of years, as the region’s climate changes and these deserts become vegetated, these sands become stabilized and they no longer move around in the wind.

Although they might not look a lot like other deserts, paleodeserts include places like the Nebraska Sand Hills in the central part of the US state of Nebraska. Nowadays, this area is fairly heavily vegetated and it receives a decent amount of precipitation, but it was once part of a massive sand sea, like what you’d see in the Great Sand Sea of the Sahara.

Extraterrestrial Deserts

Last but not least, we have the extraterrestrial desert, which is any dune field located on a planet or terrestrial body other than Earth.

For a long time, Mars was the only planet or extraterrestrial body in our solar system other than Earth that was known to have dune fields (fields of wind-blown sediment). These days, scientists have identified a number of dune fields on Venus, Mars, Pluto, and Titan (one of Saturn’s moons).

You May Also Like: Biomes Of the World: Facts, Photos and More!

Desert Fun Facts

Looking for some great desert fun facts to share with your friends and family? Here are some need-to-know desert superlatives to check out:

What Is The Hottest Desert?

The hottest desert on Earth is likely the Lut Desert of Iran. According to NASA, the desert routinely records some absurdly high temperatures, including a 159ºF (70.7ºC) extreme high in 2005.

However, note that we said “likely” when we labeled the Lut Desert as the hottest desert on Earth because the highest average annual temperatures on the planet change each year. For example, NASA’s satellite temperature data also recorded some exceptionally high temperatures in Queensland, Australia (including a 156.7ºF/69.3ºC in 2003).

Additionally, there’s a bit of controversy over what counts as a high temperature. The NASA data for the Lut Desert was collected by satellite, which is generally excluded from world high temperature superlatives.

In fact, the World Meteorological Organization’s World Weather & Climate Extremes Archives is your go-to source for verified extreme high temperatures.

Currently, the world’s highest surface temperature is Death Valley’s 134ºF (56.7ºC) record from 1913. So, you might be able to argue that the Mojave is actually the hottest desert on Earth.

What Is The Coldest Desert?

While the world’s hottest desert is a source of some debate, the world’s coldest desert is crystal clear: Antarctica.

In 1912, Vostok Station in Antarctica recorded a surface temperature of -128ºF (-89.2ºC), which is by far the coldest temperature reading ever obtained on Earth.

What Is The Driest Desert?

Although it’s located next to an ocean, the Atacama Desert of Chile is the driest desert on the planet.

Most years, the Atacama gets just a few millimeters of rain, if that.

What’s really mind-boggling, however, is that Arica, Chile in the Atacama Desert holds the world record for the longest dry period of 172 months (14.3 years). There’s also one weather station in the Atacama at Calama that’s never recorded a single drop of rain. So, you probably won’t need to pack your rain jacket on your next trip to the Atacama.

What Is The Largest Desert?

Antarctica is the largest desert on Earth at some 5.5 million square miles. However, the Sahara Desert is the largest hot desert on the planet with a land area of 3.5 million square miles and it grows larger every year.

What Is The Fastest Growing Desert?

The Gobi Desert is the fastest growing desert on Earth. Each year, the Gobi expands by about 2,500 square miles (6,470 sq. km) per year as the desert’s neighboring semi-arid grasslands become drier and drier through various processes of desertification.

Glossary of Desert Terms

Here are some need-to-know desert terms:

Aeolian features

An aeolian feature or landform is any topographic structure that’s created by the wind. The name “aeolian” comes from Aeolus who is the Greek god of the wind. Aeolian features include sand dunes, loess deposits, yardangs, and desert pavement. They’re a common sight in hot and dry deserts where there’s minimal vegetation to stabilize the sandy soil.

Arid

Something that is arid is considered to be excessively dry. This word is often used to describe deserts that receive very little rainfall, like the Atacama Desert, which receives little, if any, precipitation each year.

Arroyo

Arroyos are a type of dry channel found in deserts. They’re most commonly found in semi-arid deserts, like those in the southwestern USA, where flash flooding and occasional rainstorms cause ephemeral streams.

These fast-moving and short-lived streams cause substantial amounts of erosion, leaving behind large gullies. Arroyos are also known as ‘dry washes,’ ‘wadis,’ ‘oueds,’ and ‘coulees.’

Barchan dune

Barchan dunes are a type of sand dune that forms whenever the wind blows almost exclusively from 1 direction. They are generally crescent-shaped, with the points of the crescent pointing downwind.

This type of sand dune tends to migrate as the wind blows sand downwind. In some parts of the world, these barchan dunes can migrate hundreds of meters a year.

Desert pavement

Found in mostly flat desert areas, desert pavement is a type of surface layer that’s comprised of gravel, boulders, pebbles, and other angular fragments.

Desert pavement forms in desert regions that have very brief, yet heavy precipitation, such as in places that get occasional thunderstorms. During these storms, precipitation percolates through the soil, causing fine silt particles to slide ever so slightly downhill, leaving behind gravel and other similarly-sized particles on the surface.

Desert varnish

Found extensively across the southwestern US, desert varnish is a blackish to reddish coating on some rock surfaces.

This varnish is actually a mix of different oxides, iron, manganese, and other compounds which are taken out of the environment by tiny bacteria that live in rocky areas and then smeared all over the surface of cliffs and other outcroppings.

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples in the southwestern US used desert varnish as a type of canvas for their rock art and petroglyphs. This is because desert varnish takes thousands of years to form, yet it can be easily scratched off with a rock or a stick to create drawings.

Desertification

Desertification refers to any process where regions of previously fertile land become deserts. This process can be natural or human-caused as various factors, such as drought, widespread deforestation, and overgrazing can fairly quickly degrade the landscape.

Dune field

A dune field or ‘dune belt’ is simply a collection of sand dunes. There’s no minimum size requirement for an area to be called a dune field, but at least a few dunes are required to be classified as a field.

Dust storm

Dust storms are common occurrences in very arid locations when strong winds (generally associated with a major low pressure system) start to blow large amounts of sand, dust, and other fine particles. These storms can cause visibility to drop significantly in just a few minutes.

The word ‘sandstorm’ is generally used to describe dust storms in major deserts. Meanwhile, the term ‘haboob’ refers to a type of strong wind that sometimes sweeps across parts of the Sahara, creating massive sandstorms. However, the word ‘haboob’ is now frequently used to refer to sandstorms around the world.

Erg

An erg is another name for a very large dune field. These fields are often called sand seas due to their impressive size though there’s technically no minimum size requirement to be called a dune.

The word ‘erg’ can also be used to describe a region of fossilized dunes (dunes that no longer move) or of large sandy basins.

Erosion

Erosion is a natural geological process that takes place whenever sediments are transported from one location to another. This process usually occurs due to the movement of water (such as with a river), glaciers/ice sheets, or as a result of wind.

Erosion is responsible for the creation of many of the Earth’s surface features, such as valleys particularly in desert landscapes. Some of the many desert features created by erosion include hoodoos, mesas, valleys, arroyos, and all aeolian features (including sand dunes).

Hamada

Hamadas are a type of high-elevation desert (often located on a plateau). They feature barren landscapes that are predominately bedrock, gravel, and other larger sediments, but minimal sand. Some of the best known hamadas are in Algeria.

Parabolic dunes

Parabolic dunes are a kind of crescent-shaped sand dune. However, unlike most barchan dunes, parabolic dunes have crescent points that face into the wind. This is because most parabolic dunes have a small amount of vegetation, which helps to stabilize the sand, holding some sections of the dune in place while others erode away.

Sand dune

A sand dune is any sizable mount or collection of sand that’s formed by the wind. As the wind blows over large, sandy areas, it collects the sand, piles it up, and, over time, this sand accumulates enough to become a dune.

Seif dune

Seif dunes are a type of very long and narrow sand dune. These dunes form whenever the wind blows from multiple directions and intersects at acute angles, causing the sand to turn into a long ridge-like structure. Siefs can be found in the deserts of Libya and Iran, among other places.

Star dune

Star dunes are a funky type of sand dune that forms whenever a desert has a varied wind regime where there’s no real prevailing wind pattern.

These dunes form star-like shapes, with many ridges leading up to their summit. They generally have more than 3 ridges, each of which is formed by the movement of wind form a different direction.

Steppe

The word ‘steppe’ can refer to many different landscapes, though, at its simplest, a steppe is any arid, grassy plain, such as those in some semi-arid deserts. This term can also be used to refer to ‘The Steppe’ or the ‘Eurasian Steppe,’ which is a large steppe that covers much of Eurasia from Hungary to Mongolia.

Transverse dune

Transverse dunes are collections of barchan dunes that form a straight-ish perpendicular line to the wind. These dunes generally shift forward thanks to the erosive power of the wind, just like other sand dunes do, creating a large, active wall of sand dunes that move across the desert landscape.

Oasis

The stuff of legend, oases are real places in the desert where lush foliage can grow. These fertile areas are fed by natural underwater springs or human-created irrigation, which allow them to support standing water, plants, and animals that couldn’t otherwise exist in the arid desert environment.

Weathering

Weathering is a process where rocks, minerals, or other substances break down. The term is most commonly used in a geological sense to refer to surface rocks that are broken down by the movement of water, wind, ice, chemical reactions (such as acid rain and limestone), or through the actions of living organisms, like lichen.

However, weathering and erosion are not the same thing. Weathering does not involve any movement of rock particles while erosion is the physical transportation of particles from one place to another.