Regardless of where you live in this world, at some point in your life, you’ve probably experienced a major storm. From snowstorms to hurricanes and tornadoes, there are a whole host of different types of storms that can wreak havoc across the planet.

But, for all their dangers and hazards, there’s something fascinating about these demonstrations of the exceptional power of Mother Nature. That makes learning about the different types of storms an interesting and worthwhile pursuit.

Whether you’re a dedicated weather buff or you’re just looking to be prepared for the next bout of inclement conditions, we’ve put together his list of the 19 types of storms we experience on our home planet.

Up next, we’ll take a closer look at these different storm types so you can impress your friends and family with your weather know-how. Let’s get started.

What Is A Storm?

Before we get to our list of the 19 different types of storms, it’s important that we briefly discuss what a storm even is.

While we’ve all lived through storms at some point in our lives, defining precisely what a storm is can be a challenge.

That’s partly because the word “storm” is actually a generic term that’s used to describe a wide range of different types of atmospheric disturbances. Basically, if something greatly out-of-the-ordinary happens on the surface of the Earth, we might be able to classify it as a storm.

However, as we’ll see in a bit, not all storms are created equal. While some storms bring an array of different types of precipitation, others feature dense cloud layers, low visibility, high winds, and other types of hazards.

Nevertheless, while it’s difficult to precisely define the word “storm,” there are a few different types of atmospheric phenomena that are widely considered to be types of storms, so those are the events we’ll focus on here.

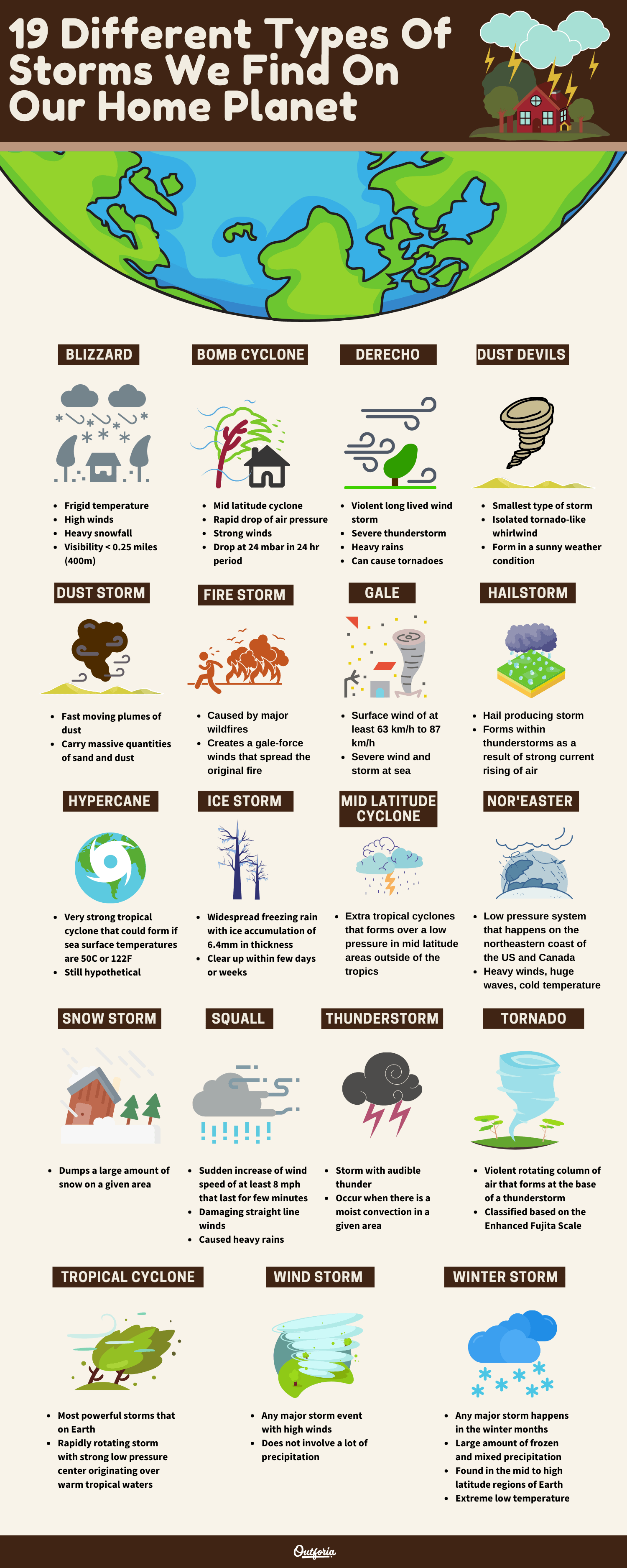

Share This Image On Your Site

<a href="https://outforia.com/types-of-storms/"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Infographic-Outforia-Types-of-storms-0721.png"></a><br> Types of storms Infographic by <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>You may also like: 24 Common to Rarest Types of Clouds with Images, Infographics and More Interesting Facts!

19 Unbelievable Types of Storms

Our wonderful planet Earth is known for having some truly outrageous weather. Here’s a look at the 19 different types of storms we find on our home planet:

1. Blizzard

First up on our list of the different types of storms is the blizzard. If you live in a cold environment, chances are pretty darn high that you’ve experienced one of these storms before.

Known for their frigid temperatures, high winds, and heavy snowfall, blizzards are a fact of life in many high-latitude locales. But, what exactly is a blizzard, you might ask?

A blizzard is technically defined by the US-based National Weather Service as a type of winter storm that features large amounts of blowing snow. To be classified as a blizzard, a storm needs to have wind speeds of at least 35 mph (56 km/h) and visibility of no more than 0.25 miles (400 m) for at least three hours in a row.

Interestingly, the definition of a blizzard doesn’t actually require that snow be falling from the sky. In fact, many blizzards, especially those in polar deserts, like Antarctica, don’t feature any snowfall at all. Rather, the lack of visibility in these storms is caused by the high winds that stir up snow on the ground, bringing conditions to near-catastrophic levels.

As you can imagine, blizzards are dangerous storms. The primary danger here is exposure to the elements, particularly as high winds and cold temperatures can lead to hypothermia. Driving in a blizzard is especially dangerous, as is hiking in high-elevation areas. So, take care when a blizzard is in the forecast as it can make navigation very difficult in the mountains.

2. Bomb Cyclone

Scary as they may sound, bomb cyclones don’t actually have anything to do with bombs. Rather, a bomb cyclone is any mid-latitude cyclone (more on that in a bit) that experiences a major and rapid drop in atmospheric pressure.

Atmospheric pressure is an important metric in a storm because storms with lower pressures tend to be substantially more destructive than their higher pressure counterparts.

This is because these super low pressures are associated with what we call a steep pressure gradient. In other words, there’s a big change in pressure over a relatively short distance within a given area. Since pressure gradients are one of the driving forces behind wind, lower pressures and, subsequently steeper pressure gradients, can create very strong winds.

Of course, there are exceptions to every rule, but often, when we see a rapid drop in surface pressure in a given area, a major storm is afoot. To start to categorize these major and rapid storm developments, meteorologists started calling some rapidly developing storms “bomb cyclones.”

The technical definition for a bomb cyclone is any mid-latitude cyclone that experiences a drop in air pressure of at least 24 millibars in a 24 hour period. These storms, like Storm Denis, which hit the United Kingdom in February 2020, can usher in truly massive winds, copious amounts of precipitation, and other similar hazards.

3. Derecho

Derechos (pronounced “deh-REY-chos”) are a unique type of highly violent, widespread, and long-lived wind storm. These storms are normally associated with large, fast-moving severe thunderstorms as they require deep, moist convection in order to form.

While the formation of a derecho is a fairly complex topic, the damaging effects of derechos are clear. Indeed, derechos can cause everything from hurricane-force winds to flash flooding, heavy rains, and even tornadoes.

Derechos are most commonly associated with squall lines, which are lines of thunderstorms that tend to form a line-shaped pattern ahead or alongside a cold front. These storms are most common in the central Midwestern US, however, they can form throughout the Eastern Seaboard of the country, especially during the warmer months of the year.

There are actually many types of derechos, including the single, multi-bow, progressive, and hybrid derecho. The difference between all of these types of derechos is a bit beyond the scope of this article, but each derecho type takes a unique shape and has certain environmental characteristics that affect the wind speeds and hazards that a storm can produce.

As we’ve already mentioned, the major hazard of a derecho is the storms’ damaging straight line winds. These winds can destroy buildings or even down hundreds of thousands of acres of trees in a single downburst. For example, the 1999 Boundary Waters-Canadian Derecho in the US and Canada toppled some 370,000 acres (149,700 ha) of trees.

Unfortunately, predicting derechos is no easy feat as the atmospheric conditions that lead to derecho formation are quite subtle. However, many weather forecasters will mention the risk of derechos in their forecasts during times of high thunderstorm danger in regions that are prone to this type of storm.

4. Dust Devil

One of the smallest types of storms, dust devils are isolated, tornado-like whirlwinds. However,

While dust devils share many physical similarities to tornadoes, they are not the same thing.

A dust devil, on average, will be no more than about 1.6 ft to 32 ft (0.5 m to 10 m) wide and 3,280 ft (1,000 m) tall. Although some tornadoes can be this small, most are substantially larger.

Furthermore, tornadoes are almost always associated with rapid air circulation that’s driven by deep moist convection in a mesocyclone of a tornado. On the other hand, dust devils can form in otherwise pleasant, sunny weather conditions in the absence of any major clouds or weather systems.

So, how exactly do dust devils form, you might ask? Well, most dust devils form when local heating of the air at the surface of a given area starts to rise quickly and form an updraft.

Should the conditions be just right, the rapidly rising air will start to circulate. This circulation, alongside friction at the surface, causes the dust devil to move forward, picking up small debris in the process. When this happens we have a fully-fledged dust devil that can travel for no more than about 20 minutes before dissipating.

The good news is that dust devils are rarely major hazards. For the most part, winds in these storms are less than about 45 mph (70 km/h) in speed so it’s rare to see exceptional damage to property or human life from a dust devil.

But, it is possible for dust devils to reach speeds equivalent to an EF-0 tornado (about 75 mph/120 km/h) and they have caused accidents in the past.

5. Dust Storm

Although dust storms and dust devils share a similar name, they actually have very little in common (besides the presence of dust, of course). In fact, while dust devils are small-scale circulating air columns, dust storms are widespread, fast-moving plumes of dust that get tossed around in arid or semi-arid areas.

The vast majority of the world’s dust storms happen in northern Africa and on the Arabian Peninsula where there are large quantities of sand and dust in one region. This sand and dust get picked up by strong winds or gust fronts that form, often in conjunction with a large thunderstorm or a cold front.

Dust storms can pick up and carry massive quantities of sand and dust, leaving behind deposits of sediment that can tower upwards of hundreds of meters high. These substantial quantities of dust can have major impacts on human health as this dust can be inhaled and cause a potentially deadly condition called silicosis.

Furthermore, dust storms have a large economic impact because they can exacerbate desertification and land degradation. For example, in semi-arid regions, dust storms can scour the land of the small amounts of nutrient-rich soil located on the surface, leaving behind little but infertile lands that can’t sustain widespread agriculture.

One of the most famous series of dust storms in recent history was that of the Dust Bowl in the midwestern United States and Canada during the 1930s. These storms were particularly bad in the region of Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Kansas, and Oklahoma, where they led to the degradation of thousands of square miles of farmland.

6. Firestorm

As their name suggests, firestorms are a type of storm that is caused by major wildfires.

Thankfully, these types of storms are fairly rare, but they can form whenever combustion in a large wildfire causes widespread air convergence at the surface of the Earth. This convergence happens as the heat of the fire causes air to rise, reducing pressure at the surface, which subsequently draws surrounding air toward the fire itself.

When this happens, the fire can spawn convective systems and gale-force winds, which only serve to exacerbate and spread the original fire. In some situations, these firestorms can create a unique type of cloud called a pyrocumulonimbus, which is a cumulonimbus that forms as a result of wildfire or volcanic eruption-driven convection.

The most obvious danger of a firestorm is the fire itself. However, as we’ve mentioned, the gale-force winds created by the firestorm can make the situation much, much worse. On top of that, if a pyrocumulonimbus cloud forms, the firestorm might also lead to a severe thunderstorm with damaging straight line winds, lightning, and perhaps even a tornado.

7. Gale

A gale is technically defined as any low pressure system not associated with a tropical cyclone that forms a sustained surface wind of at least 39 mph (63 km/h) but no more than 54 mph (87 km/h).

As you can see, this definition of a gale is quite vague. That’s partly because the term “gale” has long been used in nautical contexts to describe severe winds and storms at sea.

In the past, anything above a 7 on the subjective Beaufort Scale could be considered a gale. The Beaufort Scale, which was designed in the nineteenth century to help describe wind speed before the advent of modern forecasting tools, was based solely on visual clues, such as the size and features of the waves on the water.

National weather services around the world will still issue gale warnings (sometimes called wind advisories or storm warnings in the US) to help alert sailors, motorists, and aviators to the potential threats of high winds in the near future.

Depending on where you are and what you’re doing, a gale might not have a major impact on your activities. But, for anyone that’s on the water, in high elevation terrain, or flying a small aircraft, paying attention to gale warnings is of the utmost importance.

8. Hailstorm

Aptly named, hailstorms are a type of severe weather storm that produces hail. That being said, the term “hailstorm” is really more of a colloquial term for hail-producing storms than a scientific one.

That’s because hail tends to form as part of a severe thunderstorm and is not generally considered to be a storm type in its own right. However, the term “hailstorm” is so widely used and the dangers posed by hail are so substantial that it’s worth discussing hailstorms as a separate storm type.

At its most basic, hail is a type of frozen precipitation that forms within thunderstorms as a result of strong updrafts. What happens is that a small ice pellet will form in a cumulonimbus cloud with a strong updraft, which is a fast-moving upward-flowing channel of wind.

As small ice pellets fall toward the bottom of the cloud, these strong updrafts propel them upward, where they collide with other water molecules. Since the temperature is colder toward the top of the cloud, these water molecules supercool onto the ice particle, causing the hail to grow and grow.

When that hail eventually becomes too big for the storm’s updrafts to support, it will fall to the ground. If there’s enough hail at once, we might classify the storm as a hailstorm.

The biggest danger of hail is the possibility of injury (imagine a ball of ice the size of a golf ball falling onto your head) or the possibility of widespread property damage. Hail can actually be particularly damaging to cars and crops, causing billions of dollars in damage each year.

Since most hail is associated with severe thunderstorms, you’ll often hear about increased risks of significant hail whenever a major storm is in the forecast. But, predicting hail sizes is difficult, so it’s best to prepare for the worst whenever significant hail is in the forecast.

9. Hypercane

If you’ve never heard of a hypercane before, we don’t blame you because, well, technically, hypercanes don’t quite exist—yet.

A hypercane is actually a hypothetical type of storm that some researchers predict could happen if climate change trends continue along the same path that they’re going down with regards to the rapidly warming temperatures of the ocean.

Effectively, a hypercane is a very strong tropical cyclone that could technically form if sea surface temperatures are 122ºF (50ºC) or higher. Of course, this temperature is about 27ºF (15ºC) higher than any temperature ever recorded at the surface of the Earth’s oceans before, so this is all quite hypothetical.

But, the idea is that, if the ocean temperatures were to rise dramatically, we could see the formation of superstorms that could create wind speeds of upwards of 500 mph (800 km/h). These storms could also have central surface pressures of less than 700 hPa, which, for the record, is 170 hPa lower than the 800 hPa pressure recorded during Typhoon Tip in 1979.

Thankfully, for us humans, the likelihood of one of these hypercanes forming any time soon is pretty darn small. But there is a theoretical possibility of these massive storms on Earth.

10. Ice Storm

Unlike the vast majority of storms on our list, ice storms are one type of severe weather event that has nothing to do with violent winds. In fact, many ice storms have very mild winds because what makes these storms so dangerous isn’t what happens during them, but what happens after.

An ice storm is essentially a type of winter storm that sees widespread freezing rain with ice accumulations of at least 0.25 inches (6.4 mm) in thickness.

With freezing rain, everything from the roads to telephone poles and trees can be covered in a thick layer of ice. This thick ice layer can topple trees, pull down electrical poles, and cause major motor vehicle accidents. As a result, driving is particularly dangerous and homes may lose power for days or weeks on end.

Major ice storms can be difficult to predict, but anytime freezing rain is in the forecast, they are a concern. While most ice storms will clear up within a few days, some can persist for weeks, like the 1991 ice storm in northern New York state.

11. Mid-Latitude Cyclone

Mid-latitude cyclones, or extra-tropical cyclones, are a type of storm that forms over a low-pressure system in mid-latitude areas outside of the tropics (e.g., north of 30ºN and south of 30ºS) but to the south of the polar regions. These systems drive the bulk of the major severe weather events in non-tropical areas like North America and they can be upward of 1,000 miles (1,600 km) wide.

There are many reasons why a mid-latitude cyclone might form, though a combination of significant wind shear and a sharp gradient of both temperature and dew point is usually required, as is low-level convergence and upper-level convergence in the air column.

Now all of that might sound like a bunch of technical jargon, but the reality is that mid-latitude cyclones are complex beasts.

Nevertheless, most mid-latitude cyclones form in a similar pattern that’s known as cyclogenesis. As a result, forecasters are usually quite good at predicting major mid-latitude storm formation, even if the precise precipitation totals, storm path, and wind speeds are hard to pinpoint.

Mid-latitude cyclones can form at any time of year and they often bring large amounts of wind and precipitation. Depending on the season and region that these storms form in, they might bring lightning, snow, or both (called thundersnow). Wind speeds in these storms can be hurricane-force, too. So, these mid-latitude cyclones are no joke!

12. Nor’easter

One of the more regional-specific types of storms on our list, a Nor’easter is a major severe weather event associated with a low pressure system that happens on the northeastern coast of the US and Canada. The name is a shortened form of “northeast,” which is a reference to the fact that these storms usually bring strong northeast winds.

Nor’easters tend to form during the fall, winter, and spring, usually between September and April. They develop within about 100 miles (160 km) of the eastern coast of North America and bring with them heavy winds, huge waves, cold temperatures, and a whole lot of precipitation.

For a quick look at how these storms form, check out this video from WeatherNation:

Nor’easters are known for being tricky to forecast for meteorologists because conditions have to be just right for them to form and bring severe weather to the northeastern part of North America.

That being said, Nor’easters have been implicated in some of the worst weather events in the region’s history, including the Blizzard of 1888, and the New England Blizzard of 1978.

13. Snowstorm

As you can gather from their name, snowstorms are storms with large amounts of snow. Like hailstorms, the term “snowstorm” isn’t really a technical term, though you’ll hear people use it whenever significant snow is in the forecast.

A snowstorm is generally considered to be a type of winter storm, though, in some places, you can see snow outside of the winter season. If wind speeds are high enough and visibility is low enough, a snowstorm might also be classified as a blizzard.

Snowstorms in certain parts of the world can dump unbelievable amounts of snow on a given area. Although snowfall storms are hard to compare from place to place due to limited record-keeping systems, the highest ever single snowfall total from a snowstorm in the US was 78 inches (198 cm), which fell on the community of Mile 47 Camp in southern Alaska in 1963.

14. Squall

In meteorology, there are a number of different events that can be called “squalls.” The first type is a small storm that features a very sudden and very sharp increase in wind speed over a local area.

Many organizations will define squalls as sudden increases in wind speed of at least 18 miles per hour (8 m/s). To be classified as a squall and not a gust of wind, this increased wind speed needs to last for at least a few minutes. These squalls often form as a result of strong air sinking in the mid-troposphere.

The other type of squall you’ll hear meteorologists talk about is a squall line. A squall line is a type of thunderstorm that forms more less in a line. These storms are technically called quasi-linear convective systems (QLCS) and they often happen along a cold front.

Squall lines are known for their damaging straight line winds. They can also cause lightning, heavy rains, and even waterspouts. Tornadoes can happen along squall lines, too as squall lines are defined by high wind shear environments, which increase the risk of tornado formation.

15. Thunderstorm

At its most basic, a thunderstorm can be defined as any storm where there is audible thunder. Of course, since thunder comes from lightning, we can consider all thunderstorms to also be lightning storms.

While we don’t entirely know why thunder itself happens, we do have a fairly good understanding of why thunderstorms form. In particular, thunderstorms occur when there is deep, moist convection in a given area.

This convection is often driven by surface heating and is exacerbated by wind shear, but there can be a number of other factors at play that determine the type of thunderstorm that forms and how severe that storm actually is.

As a general rule, some of the most severe thunderstorms come from supercells, which are also known to create damaging straight line winds, tornadoes, and massive hail. In some parts of the world, particularly on open prairies, you can see these massive cumulonimbus clouds as they approach you from a distance.

Meteorologists are pretty good at predicting the likelihood of a thunderstorm’s formation, but there are always exceptions to every rule. In many locations, local weather authorities will issue tornado watches and warnings when major storms threaten.

Many people fear thunderstorms because they fear the chance of getting struck by lightning. Luckily for all of us, getting struck by lightning is quite rare, but it is possible. To minimize your risk of getting struck by lightning, seek out a sheltered area, such as a building or a forest. Avoid being on or in summits, ridges, cliffs, fields, and open water whenever possible during a storm.

16. Tornado

A tornado can be defined as a very violently rotating column of air that forms at the base of a thunderstorm. Like hailstorms, a tornado often isn’t considered to be a storm type in its own right, but due to the destructive nature of these events, they’re well worth listing here.

Tornadoes form in only a small percentage of thunderstorm clouds called supercells. These supercells feature very powerful updrafts and downdrafts due to high levels of directional and height-based wind shear. For a better look at how these complex storms form, check out this great video from NOAA:

The primary danger with a violently rotating cloud like a tornado is easily high winds. Although most tornadoes don’t reach these extreme wind speeds, it is possible for a tornado to have winds of over 300 mph (483 km/h).

In fact, tornadoes are classified based on the Enhanced Fujita Scale, which is an updated version of the older Fujita scale that was developed by legendary meteorologist Ted Fujita. The Enhanced Fujita Scale is as follows:

- EF0 – 65–85 mph (105–137 km/h)

- EF1 – 86–110 mph (138–177 km/h)

- EF2 – 111–135 mph (178–217 km/h)

- EF3 – 136–165 mph (218–266 km/h)

- EF4 – 166–200 mph (267–322 km/h)

- EF5 – 200 mph or higher (322 km/h or higher)

That being said, tornado classification is usually something that happens after the tornado ends, which makes this system different from that of a hurricane. Since pinpointing wind speeds in a tornado is very difficult, meteorologists survey tornado damage after the storm to determine its severity and approximate wind speed.

Tornadoes are arguably one of the scariest types of storms because forecasting them is really, really difficult. Even with cutting-edge forecasting techniques, tornado forecasting accuracy isn’t as good as forecasting for something like a hurricane due to the fact that tornadoes happen on a much smaller scale and are controlled by so many different factors.

While we can’t predict tornadoes with 100% accuracy at this time, if you hear a tornado warning or watch, please take it seriously! Seek out shelter as soon as you can and wait until the storm passes.

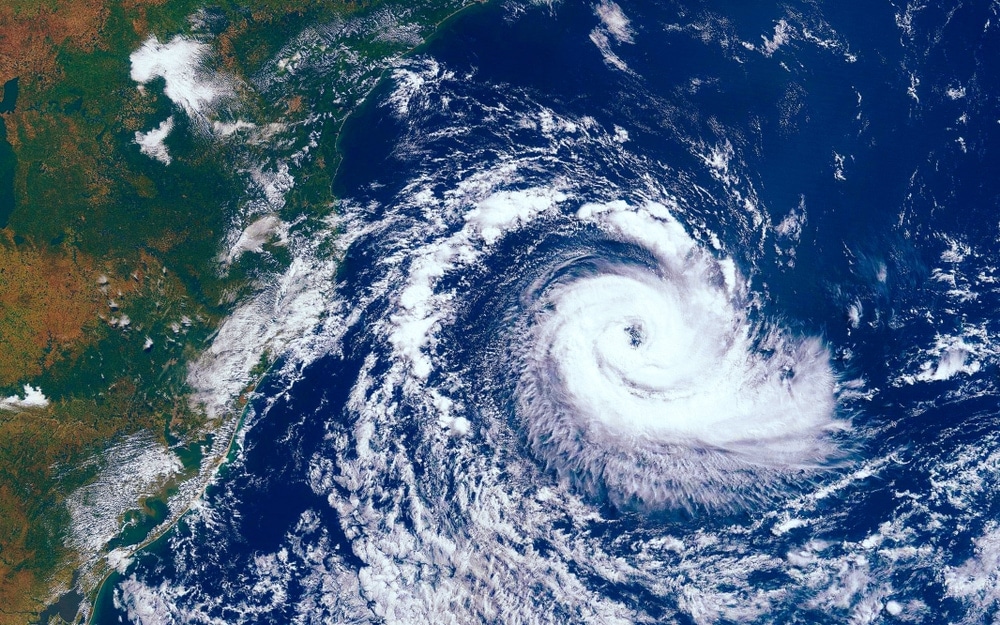

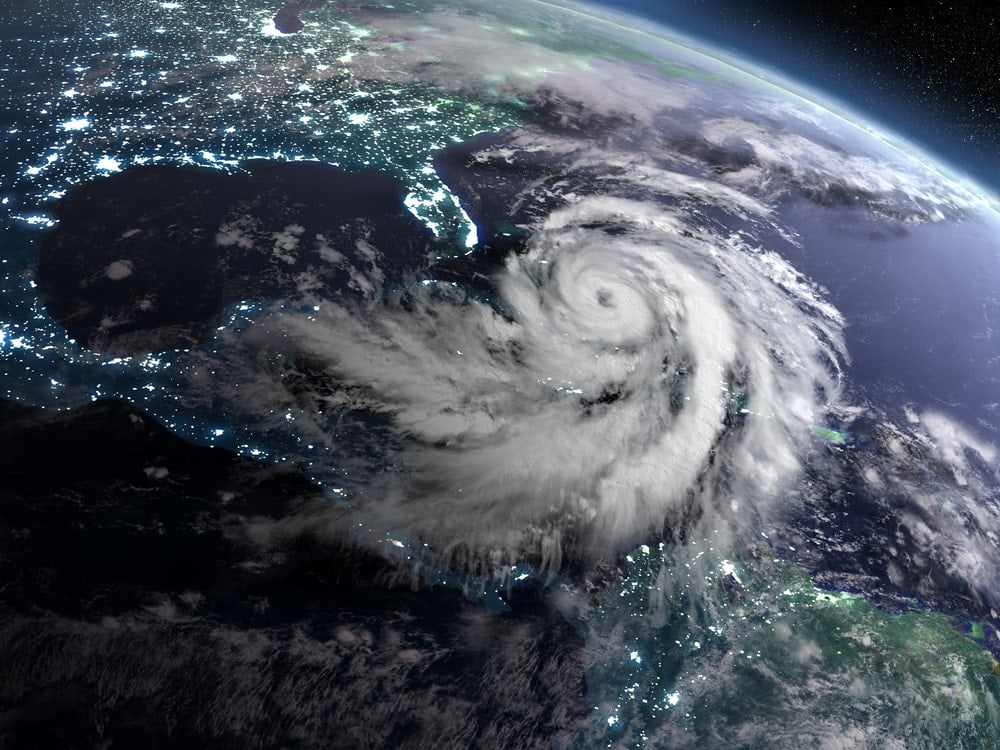

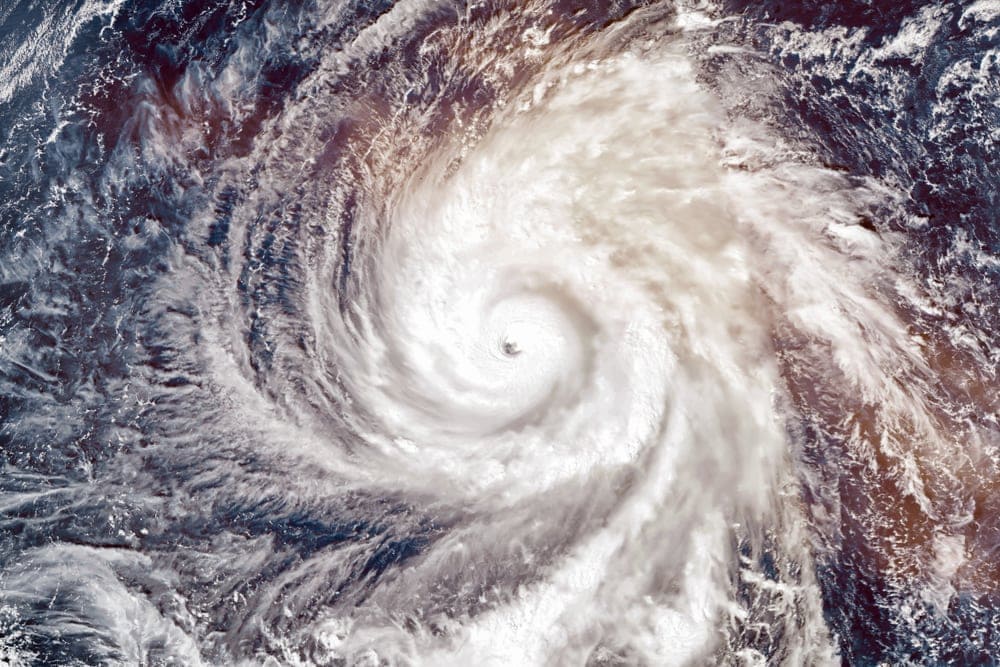

17. Tropical Cyclone

Whether you call them hurricanes or typhoons, the tropical cyclone is one of the most powerful storms that we experience on planet Earth. These storms are defined as any rapidly rotating storm with a strong low-pressure center that originates over warm tropical waters.

Tropical cyclones can affect a substantial portion of the Earth, including regions between about 30ºN and 30ºS. They can form in a number of oceanic basins, including:

- North Atlantic Ocean

- Western Pacific Ocean

- Northeastern Pacific

- Southern Pacific Ocean

- North Indian Ocean

- South-West Indian Ocean

- Australian Region

Of course, tropical cyclones have been known to move substantially further north or south than these latitudes. For example, Hurricane Faith of the 1966 Atlantic hurricane season traveled some 6,850 miles (11,020 km) from its origin and reached a latitude of 61.1ºN near Norway.

There are also many ways in which we can categorize tropical cyclones, all of which are based on the storm’s maximum sustained wind speed. The World Meteorological Organization lists the tropical cyclone classification scale as follows for the North Atlantic and Northeastern Pacific basins, using the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale:

- Tropical Depression – 38 mph or less (62 m/h or less)

- Tropical Storm – 39 to 73 mph (63 to 118 km/h)

- Category 1 – 74 to 95 mph (119 to 153 km/h)

- Category 2 – 96 to 110 mph (154 to 177 km/h)

- Category 3 – 111 to 129 mph (96 to 112 km/h)

- Category 4 – 130 to 156 mph (209 to 251 km/h)

- Category 5 – 157 mph or higher (252 km/h or higher)

However, do note that tropical cyclone categorization conventions differ from location to location, as do storm names (more on that in a bit).

The real question is: How do tropical cyclones form?

Basically, tropical cyclones feed off of the warm, moist air that’s found in equatorial waters around the world. This air tends to rise, paving the way for the formation of massive low pressure systems. As this warm air rises, the air that converges at the surface will eventually start spinning due to friction and the Coriolis effect.

As you can imagine based on the wind speeds that we discussed above, one of the major hazards of a tropical cyclone is high winds. While these winds can and do cause a lot of damage, often the biggest hazard with tropical cyclones is the storm surge, rainfall, and flooding that accompanies these storms.

Luckily, modern forecasting techniques have made it fairly easy for meteorologists to identify tropical cyclones, even if forecasting their precise wind speeds and paths isn’t that straightforward. Needless to say, if there’s an evacuation order for your area during a tropical cyclone—listen to it! These storms mean business and shouldn’t be messed with.

18. Windstorm

While more of a colloquial term than a scientific one, a windstorm can be defined as any major storm event with high winds.

Some people would argue that a storm isn’t a windstorm unless the winds are strong enough to damage buildings or trees. However, as there is no real precise definition of a windstorm, it’s hard to make such a distinction.

Either way, what differentiates a wind storm from other types of storms with windy conditions is that your standard windstorm often doesn’t involve a lot of precipitation.

There are also regional-specific types of windstorms, such as the European windstorm. A European windstorm is a type of mid-latitude cyclone that directly affects continental Europe, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and the British Isles. These storms can bring heavy winds and, as a result, they tend to cost nearly €4 billion each year in damages and insurance losses. Yikes!

19. Winter Storm

As the name suggests, a winter storm is any type of major storm that happens in the winter months. Of course, these storms normally include large amounts of frozen or mixed precipitation, such as snow and freezing rain, and they are generally only found in the mid- to high-latitude regions of Earth.

Interestingly, a blizzard is a type of winter storm, but not all winter storms classify as fully-fledged blizzards. Rather a winter storm doesn’t have to meet any specific wind speed and visibility requirements like a blizzard does.

Most winter storms form when there’s widespread uplifting of an air parcel over a region, which contributes to the formation of a low pressure system. When conditions are just right to allow for winter storm formation, you can expect anything from a few inches to multiple feet of snow and ice pellets.

Oftentimes, the biggest threat of a winter storm isn’t the snowfall (though this can, of course, be a hazard). In many situations, very cold temperatures can cause major problems for individuals and communities. Beyond the threat of hypothermia and frostbite brought about by cold weather, extreme low temperatures can also overload power grids and cause blackouts.

Meteorologists have gotten pretty good at predicting winter storms, so you’ll often have plenty of warning before one arrives. But, it’s worth having extra food, water, and cold weather supplies on hand at all times if you live in a region that often gets hit by winter storms.

You may also like: The 9 Types of Weather that You Must Know and Where To Get Weather Forecast: Complete with Images, Facts, Descriptions, and More!

How Are Storms Named?

Storming naming is a complex topic because each weather forecasting organization has different conventions for how and if they name storms. Since storm naming is such a broad topic, we’ll focus specifically on naming conventions for tropical cyclones, which are the most common types of storms to be named.

At its most basic, storm naming is a simplified way to communicate information about a storm, both between meteorologists and with the general public. It’s easier for governmental organizations to give warnings about a major storm if it has a short, catchy name that people can remember.

Think about it: Would you be more likely to remember the name “Hurricane Laura” or the name “Hurricane 20B17D”? Clearly, a tropical cyclone with a simplified name will be easier to remember than a nonsense string of numbers and letters.

However, while meteorological associations around the world agree that we should name tropical storms, no one is in agreement about how we should do so. As a result, tropical cyclones have different naming conventions depending on which basin they form in.

US-Based Hurricane Naming Systems

In the North Atlantic and Northeastern Pacific tropical cyclone basins, the United States’ NOAA National Hurricane Center is in charge of naming. Initially, all storms were given female names but, by 1978, storms were given names that correspond with any gender.

Nowadays, NOAA maintains three lists of hurricane names (one for the Atlantic and two for the Pacific) from A to Z that rotate on a four to six year cycle. So, the first storm name of the season will start with an A and the final name will start with a W or Z (we have a limited number of names that start with X, Y, and Z, unfortunately).

What happens if there are more storms in a given season than there are names on the list, you might ask? Well, before 2020, Greek alphabet letter names were used after the last name on a hurricane season’s list (e.g., Hurricane Zeta). However, as of 2021, NOAA will now use a list of supplemental names to limit confusion and enhance communication during storms.

However, storms that are very severe, very deadly, or very costly have their names retired. Doing so eliminates the possibility that a catastrophic storm’s name will be repeated in the future, which might be considered insensitive.

For example, there will never be another Hurricane Katrina nor another Hurricane Harvey due to the massive amount of destruction that these storms caused. You can check out the complete list of retired hurricane names on the NOAA website.

Non-US Tropical Cyclone Naming Systems

For tropical cyclones that form outside NOAA’s weather forecasting jurisdiction, different naming conventions are used. For example, the Japan Meteorological Agency names storms in the Western Pacific while Météo France names storms in the South-West Indian Ocean.

Each organization has its own unique naming conventions, most of which use local names for ease of communication in that region.

It’s worth noting that, generally, once a hurricane is named by a given organization, it keeps that name, even if it moves into another basin. The only current exception to this is if a typhoon threatens the Philippines.

When there is a risk of a typhoon impacting the Philippines, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) gives the storm a unique name.

These names have been chosen because they are common in the Philippines, which makes it easier for people in the country to remember the storm’s name. Research had shown that there were communication issues surrounding typhoons in the Philippines because most of the storms were named by other non-Philippine organizations.

To combat this issue, the Philippines issues its own names for storms. This does mean that some storms have multiple names, such as the Category 5 storm Typhoon Haiyan, which was known as Super Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines.

You may also like: Find Out What Causes Tides: Complete with Illustrations, Explanations, Descriptions, and More!

Storm Superlatives: The Worst Of The Worst

At this point, you’re a knowledgeable storm chasing enthusiast. But, how much do you know about the planet’s most extreme weather events? Let’s take a look at some of the worst storms on record:

Most Intense Tropical Cyclone: Typhoon Tip

Since there are so many ways to evaluate the severity and intensity of a tropical cyclone, we’ll stick with two measurements here: total size and lowest recorded sea-level pressure. Within those two measurements, Typhoon Tip (Typhoon Warling in the Philippines) is the clear winner.

Typhoon Tip formed in the Pacific Ocean in October 1979 and reached a total size of more than 1,380 mi (2,220 km). It also had an all-time record low pressure of 870 hPa recorded at its peak intensity. Unfortunately, Typhoon Tip also killed at least 99 people across its path.

Harshest Blizzard: 1972 Iran Blizzard

As we’ve mentioned, comparing snowfall totals around the world isn’t easy, but when it comes to blizzards, one storm stands out among the pack in terms of severity: the 1972 Iran Blizzard.

The 1972 Iran Blizzard was a week-long storm event that dumped more than 9.8 ft (3 m) of snow across Iran. It’s believed that at least 4,000 people died during the storm, many of whom were buried by the high snowfall.

Fastest Tornado Wind Speed: 1999 Bridge Creek Tornado

Tornadoes are known for their unbelievably fast wind speeds, but not all tornadoes can match the speed of the 1999 Bridge Creek Tornado in the US state of Oklahoma.

This tornado set a world record with a total whopping wind speed of 302 mph (486 km/h), which makes it solidly an EF-5 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale.

However, do note that this wind speed was assessed by doppler radar algorithms, so it’s not technically a “measured” wind speed. But, due to the relative scarcity of weather stations around the world and the fact that a tornado of this size likely would’ve destroyed a weather station anyway, we can still crown the 1999 Bridge Creek Tornado as the fastest on record.

Costliest Hailstorm: 2001 St. Louis Missouri Hailstorm

As far as historic hailstorms go, the 2001 St. Louis Missouri Hailstorm is tough to beat. This storm dropped massive amounts of hail across the state of Missouri and southwestern Illinois, leaving behind hailstones that were up to about 3 inches (7.6 cm) in diameter.

When all was said and done, this hailstorm resulted in about $12 million worth of damage (in 2001 dollars), making it the costliest hailstorm in US history. Due to cost of living differences in various countries, making international hailstorm cost comparisons is inherently problematic. However, this 2001 hailstorm was certainly a pricey event!

You May Also Like: Find Out How Climate Change Affected These Landmarks

Types of Storms FAQs

Here are our answers to some of your most commonly asked questions about the different types of storms:

What Types of Storms Are Named?

Although storm naming conventions vary from region to region, the most common storm type to receive a name is the hurricanes (also known as typhoons). In some countries and regions, however, major winter storms and other mid-latitude cyclones also get names. But, this is more common in the United Kingdom than in the United States or elsewhere.

What Is the Smallest But Most Violent Storm?

Although it can technically be considered a part of a storm, rather than a storm in its own right, a tornado is generally regarded as the smallest but most violent storm. With the ability to have wind speeds that can exceed 300 mph (480 km/h), tornadoes are often substantially more violent than hurricanes, blizzards, or other much larger storms.